Weekly Roundup, 27th September 2016

We start today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with the Chart That Tells A Story. This week it was about the price of oil stocks.

Contents

Oil stocks

Naomi Rovnick compared the price of FTSE-350 oil stocks with that of Brent crude.

- Oil is still below $50 a barrel, compared with a peak of $120.

- The companies have recovered better, and are back to 2011 levels.

- BP is above its price five years ago, while Shell is just below.

This should mean that the market expects a further recovery in the oil price.

- Bloomberg quotes analyst forecasts of $56 next year and $62 in 2018, from today’s $47.

It also partly reflects expectations that oil companies will drive down costs, and hence increase profits.

But another big factor is dividends.

- BP and Shell still yield around 7% each, even at these potentially inflated prices.

- The dividends should be covered by profits in 2016, but only just.

- The traditional safety level of two times cover won’t be met.

Looked at from a cashflow rather than a profits perspective, Goldman Sachs estimate that Shell and BP need an oil price north of $60 to generate enough cash.

- So if the oil price stays low, we can wave bye-bye to the high dividends over the next couple of years.

Rebranding pensions

This week’s public figure spouting nonsense was ex-Pensions Minister Steve Webb.

Josephine Cumbo reported that he would like the word pension replaced by something more appealing to the youngsters.

- Apparently pension makes them think of smelly old pensioners. ((As an official pensioner, I won’t be drawn on what the word millennial makes me think of ))

- Steve suggested Freedom Pot.

I think he’s missing the point.

There are two reasons why young people don’t put enough money into pensions, despite the attractions of up-front tax relief:

- they don’t have enough spare cash ((We can debate whether they spend too much on mobile phones etc, but the end result is the same ))

- they don’t like their money being locked up for 30 years or more.

These are the same two reasons why hardly anyone of my generation was saving before the age of 35.

- It’s not a new problem, it just gets a lot of airtime these days.

Auto-enrolment (with higher contributions than the planned 8% pa – possibly mandatory) is the answer, not a new name for the pot.

Buy to let

Judith Evans looked at how things have gone sour for buy-to-let.

Apart from the regular hassle of chasing down tenants for the rent, public opinion has turned, and the National Landlords Association reports that one-in-five landlords – one in four in London – is too embarrassed to admit it. ((It’s not something I shout about, even though I qualify as an “accidental” landlord, and my half-share in my Dad’s old house in Manchester is leased to a Housing Association, who are presumably making sure that someone deserving is living in it ))

Prices are high these days, and though rents have increased, yields are low.

- And the tax situation for offsetting mortgage income is deteriorating.

Judith brings up a point that has long puzzled me.

- Why is private sector renting dominated by small landlords, rather than big institutions (like insurance companies and pension funds)?

It’s the fact that buy-to-let exacerbates the “haves and have-nots” social divide around property that gives it a stigma.

- And asset managers should be crying out for long-term assets with dependable yields.

Apparently the new housing minister Gavin Barwell is keen on institutional landlords, so perhaps things will change.

- I’d certainly welcome an easy way to buy into exchange-listed residential property.

Nick Train

In Money Week, Merryn interviewed Nick Train, who manages the Finsbury Growth and Income Trust.

The way Nick describes it, investing is simple.

- He just buys good stocks that he thinks will go up.

- And then they do.

Merryn thinks – like Warren Buffett, and myself – that investing is simple, but not easy.

- The sensible strategies work when you back-test them, but most people don’t have the personality to stick with them.

Merryn asked Nick which other fund managers he likes.

- Apart from Neil Woodford, the other two (Anthony Bolton and Richard Hughes) will both be retired soon.

- So not much help there.

Other tips include:

- Discipline – stick to your own rules.

- Don’t trade too much.

- Don’t chase speculative ideas.

- Don’t confuse economies with stock markets.

- Don’t be pessimistic – history is on the side of the optimists.

Nick is expecting multiple expansion as the capital intensity of quoted companies declines in response to digital technology becoming a bigger driver of profits.

- This will increase cash flows, and result in higher dividends and more buybacks.

He also expects retailers like Burberry to develop online relationships with their customers, which will mean that (like banks) they will need far fewer bricks and mortar branches.

Finally, he thinks that most people don’t have enough money invested in equities.

- I agree.

Low interest rates

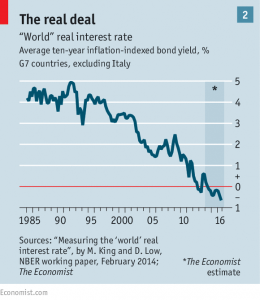

The Economist had two articles (1 and 2) about the low-interest rate world that we live in.

- Central banks think that ultra-loose monetary policy is still needed to prop up weak economies.

- Only the Fed seems keen to raise rates at the moment.

The fundamentals for the world remain poor, with ageing populations everywhere and the ever-more important China saving a lot.

- This means a savings glut, and downward pressure on rates.

But negative yields on many government bonds (and now some corporate bonds), along with charging savers a fee, means that many other people think that things have gone far enough.

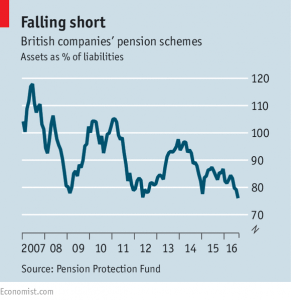

And the consequences of low rates are clear:

- pension deficits are booming, as the “duration mismatch” means that low rates inflate liabilities more than assets

- banks and insurance companies are struggling to stay profitable

- we have a bond bubble ready to burst

On the plus side, they help governments service their enormous debts.

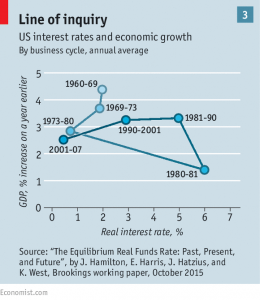

The Economist would like to see a shift from central banks and monetary policy to governments and fiscal policy.

- Back in the 1960s and 1970s, government “stimulus” (lower taxes and higher spending) led to inflation.

The newspaper thinks that the traditional infrastructure spending is needed (and should be welcomed by pension funds, as per the consolidated buy-to-let that we mentioned earlier) but it’s not enough.

- They would also like to see private-sector partners involved to ensure no white elephants.

What is needed is counter-cyclical fiscal tools that are automatically switched on and off.

- The duration and level of unemployment benefit could be linked to the level of joblessness.

- Sales tax (VAT) and savings allowances could vary in line with the state of the economy.

These are interesting ideas, and I would like to see them explored further.

Interest rate differentials

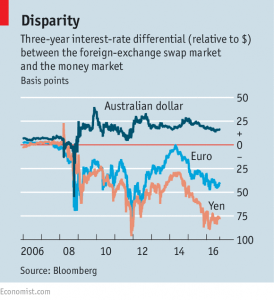

Buttonwood looked at a measure that shows that markets are not as liquid as they used to be, as discussed in a new paper from the Bank for International Settlements (BIS).

“Covered-interest parity” states that the difference between the spot price for an FX pair and its forward price (at some point in the future) should equal the interest rate differential for the period.

- So if US 1-year rates are 4% and Japanese rates are 2%, Japanese investors will buy dollars, invest them at 4% and buy a forward FX contract to insure the exchange rate risk.

- This should eventually push the dollar 2% cheaper in the forward market than in the spot, arbitraging away the profit.

This rule has been broken regularly since 2008.

One reason is that some people have to hedge no matter what.

- A European pension fund investing in “safe” US Treasuries must hedge back to Euros, as that’s the currency that its liabilities are in.

- Banks will also have mismatched assets and liabilities that they need to hedge.

More people need to hedge dollar exposures than the other way around, so interest rate differentials appear.

- These should be arbitraged away, and the fact that they aren’t suggests that markets aren’t liquid enough (banks can’t lend enough capital) and markets aren’t efficient.

It also means that in the next crisis, markets will freeze more quickly, and asset prices will get more out of line than before.

- Massive central bank liquidity will be needed to fix things.

Norway’s ethical sovereign fund

Norway has the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund at $882 bn, after only 20 years of payments in.

- Returns have been modest, at 5.5% pa compounded.

- It may have missed out on more than $100 bn extra by not investing in emerging markets and unlisted infrastructure.

It also has an ethical investment policy, and so missed on gains in tobacco and weaponry.

- Fighting excessive executive pay and climate change are also now high on the agenda.

- Oil, sugar and fast food are being discussed as future targets.

Nevertheless, it now owns 2% of listed shares in Europe and 1% globally, a total of 9,000 firms in 78 countries.

- It’s annual revenues are now bigger than the country’s oil income.

The fund is run by a unit within the Central Bank and every investment is listed online.

- The government can only withdraw the expected returns each year (conservatively estimated at 4%), leaving the capital untouched.

There had been no net withdrawals until this year.

- Since returns were low, the capital of the fund also fell slightly, too.

It will be interesting to see if the ethical policy survives into the decumulation phase.

Oxfam’s inequalities

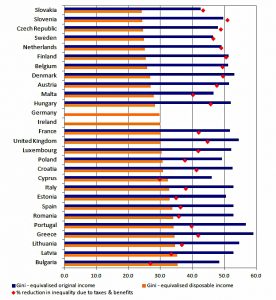

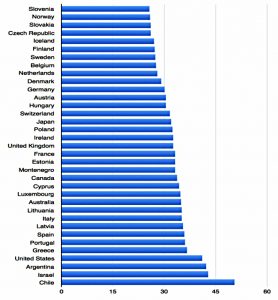

Oxfam has been making some misleading statements about inequality, and the BBC (who else) has been publishing them more widely – as Chris Snowdon has pointed out on the IEA blog.

- Ignoring the fact that inequality in Britain has little to do with Oxfam’s mission of famine relief abroad, what they say isn’t true.

Income inequality is average by European standards, and lower than the global average.

- This is largely down to the high level of redistribution within the UK tax and benefits system.

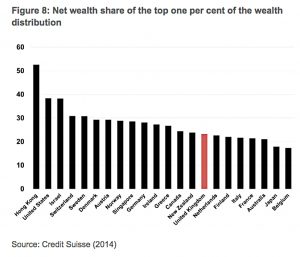

UK wealth inequality is also lower than global averages.

The confusion stems from a mistake in an OECD report which gives the UK a Gini coeficcient of 36 (the real figure is 32).

- This made the UK higher than the income inequality average for the 35 OECD countries, though not globally.

And the Oxfam report quoted by the BBC was talking about wealth inequality rather than income inequality.

There are two problems with looking at wealth inequality:

- the poorest people are unlikely to have much if any wealth

- some studies include debt, concluding that Western students are amongst the poorest people in the world

- most people’s wealth is tied up in their house, which means that countries with expensive houses (like the UK) appear to be (half-) full of very rich people

- people who live in council houses will by contrast appear to be poor

It’s worth noting that global inequality (between countries, rather than within them) is still decreasing, as it has been for 30 years.

Bake off

I never thought that I would be writing about the Great British Bake Off (GBBO), but the amount of noise this has generated has made it impossible to ignore.

The key argument is about the role of the BBC as a publicly funded broadcaster, as discussed by David Waywell on CapX. ((I’m afraid I couldn’t find a picture of David ))

- If the BBC wants to be a commercial broadcaster of celebrity banality and Saturday-night shiny floor shows, then it should find an alternative source of funding rather than reply on a compulsory tax on every household.

Alongside the elitist programmes that wouldn’t get made elsewhere ((That is, the only ones I’m interested in), there might well be a role for the BBC in developing new formats and finding new talent.

- The early series of GBBO (on BBC2) could well fall into that remit.

But now that the show is successful and populist I would argue (though David disagrees) that it no longer belongs on the BBC.

- Certainly if it were to remain, it should not be on normal commercial terms (ie. £25M per series).

There is a debate to be had as to whether the Beeb deserves some kind of ongoing interest in the profits of a show it has helped to grow, but that isn’t the way that TV contracts work at the moment.

- Instead we have the Bosman rule as in football, where a transfer to a rival costs nothing at the end of a contract period.

Now that we are leaving the EU, we can presumably leave the Bosman ruling behind as well – in TV, at least.

Until next time.