Weekly Roundup, 4th October 2016

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with the Chart That Tells A Story. This week it was about the next UK property hotspots.

Contents

Property hotspots

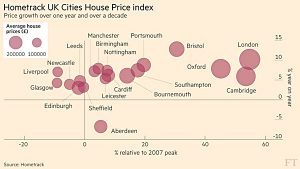

James Pickford looked at data from Hometrack (a housing research group) that compared 12-month performance with performance since 2007, by city.

- London, Cambridge and Oxford have the largest long-term gains, up around 50% on average.

- But following the stamp duty changes and Brexit, prices having been coming off their highs recently.

- London is still expected to grow, but “only” by 6% in 2016 and 2% in 2017.

- Aberdeen is the worst performer, following the oil price crash.

Hometrack is predicting that the best prospects for the future are Liverpool, Glasgow, Birmingham and Manchester.

- I can’t see it myself.

Bristol is also doing well, but from a low base.

The other point that James makes is that first-time buyers are increasing in number much more quickly outside the capital.

- No surprises there.

Pension income

Don Ezra looked at four ways to get income from your pension. ((Don’s written about decumulation before, but he’s one of the few people who does, so it’s always worth a refresher ))

- Buy an annuity

- This is not good value – Don quotes Meir Statman about a friend: “Yesterday I was a millionaire. Today I’m living on $80K a year”

- And that was back in the good old days of high interest rates.

- Now it would be $25K a year.

- With an annuity, your income is low, you have lost control of your capital, and unless you live to a ripe old age, you will never get your money back.

- Annual drawdown based on life expectancy.

- Here you just divide the pot by how many years you think you have left and withdraw that share.

- There will always be something left in your pot, so you will never have nothing to live on.

- But if you do live a long time, your annual income will eventually decline severely.

- A workaround is to add a fixed amount of time to your life expectancy (Don recommends six years).

- That way the pot declines much more slowly (but you have less to live on in the early years).

- Buy a deferred annuity (what Don calls longevity insurance) and draw down the share of your remaining assets that will last until the annuity kicks in.

- So if you are 55, you might buy an annuity that kicks in when you are 80.

- Say this costs you one-third of your pot, ((A complete guess – don’t rely on this figure )) then you would withdraw one 25th of the remaining two-thirds each year between 55 and 80.

- That works out at around 2.7% of your original pot each year.

- The big problem with this approach is that deferred annuities aren’t available in the UK (yet?).

- The fourth approach is to assume you will live to a ripe old age (95 or 100) and draw down that share that lasts until then.

- So if you retire at 55 you might draw one 40th each year, or 2.5% of your pot.

- It has more risk than option 3, but then option three isn’t available here.

Alternatively, you could always use a modified “4% rule”.

- I would recommend 3% rather that 4% given current economic conditions.

- That way you have more to live on right now, and you are still unlikely to run out of money in the long run.

Niche income

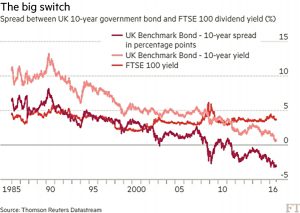

Aime Williams looked at the hunt for income.

- The headline claimed that investors were heading into niches, but there weren’t any that we hadn’t come across before.

Until 2008, income investors used mostly bonds, and some high dividend stocks.

- As bond yields fell, they switched to “bond proxies” – utilities, telecoms, oil (at the time) and pharma that could be relied upon for safe dividends.

But fourteen of the FTSE-100 stocks have cut their dividends in the past two years.

- Things have got so bad that the Investment Association is thinking of scrapping the yield target for income funds (because managers keep missing it).

So the new fad is for investment trusts, particularly in property (GP surgeries and student accommodation), infrastructure and private equity, but also P2P lending and renewable energy.

- We came across most of these a couple of weeks ago in our investment trust round-up.

Ones that we missed include:

- EMP (Empiric Student Property) – 5.2% yield but with a 12% premium to NAV

- GCP Student Living – 4% yield and an 8% premium to NAV

- GCP Infrastructure

- Darwin Leisure Property (caravan parks)

I’ll add them to the list in due course.

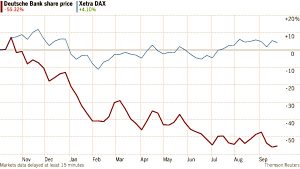

Deutche Bank

The FT had a nice article on the problems at Deutsche Bank (DB), written by Laura Noonan.

- The key point was that the crisis is not about exposure to bad loans, or the leverage from derivatives.

- It is about liquidity, and pricing uncertainties.

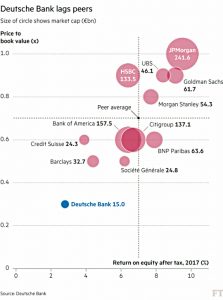

The bank has tangible assets worth €53 bn, but a market cap of only €16 bn.

- It does have low earnings, and a large fine from the US Department of Justice hanging over it.

It also has a €1.8 trn balance sheet, in which the €37 bn “gap” is just a rounding error.

- That’s the problem with valuing banks – what they are worth is a “big” number which is the difference between two very big numbers, so it’s easy to come up with the wrong answer.

The problem isn’t with bad loans.

- DB has only 25% of assets in loans, and they are mostly high-quality and in Germany.

One problem is market assets known as “level 3” – these are assets that are illiquid and are priced using models that rely on “unobservable inputs”.

- They include long-dated interest rate swaps, equity stakes in companies and exotic sovereign debt.

DB has €29 bn – half of its tier one capital – in level 3s.

- It also has €11 bn of level 3 liabilities.

- This is a higher percentage than everyone but Barclays and Credit Suisse, and a worse ratio to the bank’s market cap than everyone.

But a normal discount for level 3s might be 30%

- This explains less than €10 bn of the €37 bn hole in DB’s valuation.

So investors seem to be assuming that everything in DB’s level 3 pot is junk, and that DB is one the wrong side of every trade.

- A contrarian trade for the brave?

How to buy gold

Naomi Rovnick (or rather two IFAs that she asked for their opinions) answered a reader’s question about the best way to buy gold.

Gold tends to hold its value, does well in a crisis, and though volatile, it’s not massively correlated to shares.

- But it doesn’t produce an income.

- And it’s measured in dollars, so it does well when there’s a dollar crisis.

- If the Fed starts to raise rates, the gold price should soften.

- 5% of your portfolio is enough for most investors.

The three basic options for buying gold are bullion, ETFs and mining shares.

- Shares are not a pure play – the management and geography come into play

- That said, they can be a leveraged play when times are improving.

- Holding bullion directly is expensive (it needs to be in a vault to qualify for a SIPP).

- Not surprisingly, the IFAs plumped for physically backed ETCs, such as the ones from iShares, ETF securities and Source.

- These are backed by bars of gold in a vault.

Roll the potato

Movie buffs may recognise the title of this section as a quote from Mickey Rourke. “Every once in a while you’ve gotta roll the potato.” ((The quote came to my attention 25 years ago when Joe Queenan wrote an article for MovieLine called “Mickey Rourke for a Day” – look it up, it’s funny ))

- Tim Harford’s piece this week was in fact called “Roll the Dice“, but the sentiment was the same.

[amazon template=thumbnail&asin=0006513905]

He began by talking about Luke Reinhardt’s cult pseudonymous novel “The Dice Man”, about a guy who makes all his decisions by rolling a dice.

- Though the novel ends badly, Tim thinks that more randomness would be good for us.

- People are stuck in the status quo, and committing to what the dice says can get us to change something that we needed to.

[amazon template=thumbnail&asin=0141019018]

I re-read the Freakonomics books on holiday this summer.

- Steven Levitt (one of the authors) famously launched FreakonomicsExperiments.com to get people to submit life-changing decisions to the toss of a digital coin.

- When he followed up with people, the ones who had made the big change tended to be happier.

It seems that when we are wondering whether to change things, the right answer is usually yes.

Tim also mentions the data from Tube strikes, which force people to change their route to work.

- About 5% never go back to their old route, having found a better one through necessity.

This is the way that many computer algorithms “learn” – they throw in a bit of randomness to see if it improves things.

- Apparently Brian Eno uses cards (the “Oblique Strategies”) to produce music albums in a similar fashion.

There’s one other useful way to exploit randomness that Tim doesn’t mention.

When you think you are stuck between two options, toss a coin to see which one to do.

- When the coin is up in the air, you’ll know which way you want it to land.

- Ignore the coin, and do the thing you were hoping to do.

Corporate bond QE

Neil Collins was not happy about the latest developments in the Bank of England (BoE)’s QE programme.

- The bank now has £10bn (a tiny amount compared to the rest of QE) to spend on corporate bonds of companies that make a “material contribution to economic activity in the UK”.

This includes tax-dodging Apple, plus McDonalds as well as Unities Utilities and Rolls-Royce.

- It doesn’t include useful but struggling EnQuest, a North Sea Oil producer.

£10bn is a lot in the corporate bond world, and this will likely push prices up and yields down.

- The big boys don’t need the opportunity to borrow even more cheaply.

- The impact from lower yields on their pension scheme deficits will probably make them less likely to invest in the UK , not more.

Neil is right on this one.

Central bank distortions

Buttonwood also looked at how central bank policy is distorting the corporate bond and equity markets.

- The Economist was concerned that corporate bond and equity QE (equities in Japan only, I think) would focus on the most liquid and least risky issues, and the ones more likely to perform well.

- The recent ECB announcement has reduced the spread (over government bonds) on those eligible corporate bonds from 100 basis points to 44 (more than half).

- The spread on ineligible bonds has only fallen from 154 to 104 (less than a third).

Like Neil, Buttonwood wonders why Walmart bonds will be bought by the BoE, but not those of Tesco or Morissons.

- The lower yields will hand Walmart (who own Asda in the UK) a competitive advantage.

- And how will buying bonds from Apple, Daimler or Pepsi help at all?

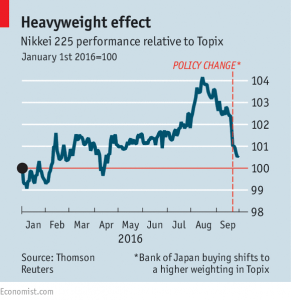

The Bank of Japan (BoJ) has already been forced to modify its equity purchase programme after distorting the market.

- The Nikkei-225 index uses the anachronistic share price weighting of the Dow index in the US.

- The BoJ purchases affecting the prices of smaller companies, so they have switched to the market-cap weighted Topix index.

And one final problem is that nobody has any idea how the banks will eventually get rid of their holdings.

NHS letters

The letters page of the Economist had some useful points to add to our recent discussions around the NHS:

- a royal commission from as far back as 1979 found that ageing demographics and technological advances would push up the NHS bill

- therefore priorities for spending needed to be established

- nearly 40 years later, every government has kicked this can further down the road

- charging for services at the point of access is not without risk, since some genuine users will not be able to tell whether they are frivolous users, or in need

- the switch to prevention over cure might need to take into account the vending machines in GP surgeries “selling cola, Lucozade and Mars bars”

Limited liability

Schumpter defended limited liability.

- The point of the concept is that the limited downside risk encourages investment, allocating capital to productive uses.

But this asymmetry (the upside is potentially unlimited) is seen by some as a subsidy from society.

- In particular, victims of corporate wrong-doing have less assets to claim.

And so the concept of “piercing” (of the corporate veil) has arisen.

- Popular in emerging economies like China and Brazil – as well as the US – this allows judges to expose shareholders to personal liability if they decide that the company was not acting fairly.

Since the average holding period for shares is now 22 seconds (!), veil-piercing is likely to become ever less useful, since it will be difficult to determine who is liable for what.

- It might be better to prosecute managers rather than pursue shareholders.

Some people (Ronald Green, Will Hutton) are now arguing that limited liability should be a privilege reserved for companies acting with social responsibility (so-called “concession theory”).

But limited liability makes society as a whole richer, increasing the amount of productively invested capital and – via the formation of small firms – increasing the number of jobs.

- What is that if not socially responsible?

Banks may be the one sector where unlimited liability would be a better fit, but even here regulating for the use of more equity is probably the best solution.

Youth of today

The inter-generational war has flared up in the media again this week.

- we’ve had a labour MP ask for better incentives for younger (and poorer) people to save for their pension

- and it’s emerged that those born in the 1980s have less in savings than those born in the 1970s

What’s really going on?

Over on The Vision of the Pension Playpen, ((An unusual name for a blog )) Henry Tapper looked at how best to get “generation rent” to save.

Their current priorities are:

- pay the bills

- have a plan to stop renting

- manage down (or at least not up) their debts

What they need is to be taught about “the impact of inflation, the growth and income properties of real and fixed assets, the cost of providing a lifetime income and the help they will get from the State through taxation and the payment of national insurance”.

The Institute of Fiscal studies reported that those born in the early 1980s have net wealth of £27K, compared to those born in the 1970s, who had £53K at the same stage.

- Flip Chart Fairy Tales (amongst others, but notably well) took a look at why.

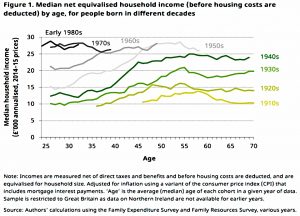

The young have higher incomes than most previous generations – around level with the 1970s, but getting on for 40% higher than my own cohort (1960s) at the same age.

- There does now seem to be a stalling of incomes after the age of 30 that wasn’t seen amongst those born in the 50s and earlier.

- This is also affecting those born in the 1960s, which is probably why they don’t like being lumped in with the Baby Boomers above them.

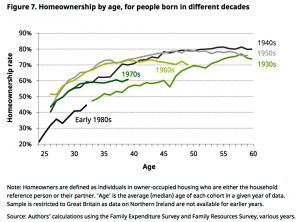

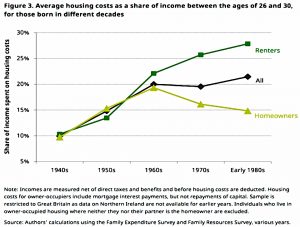

Those from the 1980s are less likely to own a home than the generations before them, and they spend more money on rent.

- Housing costs were high for those born in the 1960s, too, but they mostly bought.

- There’s a big split in those from the 1970s and 1980s between buyers and renters.

Houses cost a lot today, but interest rates are low, and 1980s buyers are paying less as a proportion of income than any generation since the 1940s.

- The problem is getting hold of the capital in the first place.

- So if you think there is wealth inequality now, wait until those in their 30s have made it into their 50s.

But housing is not the real problem.

- If you really want a house, you “just” have to give up on London and move to Manchester.

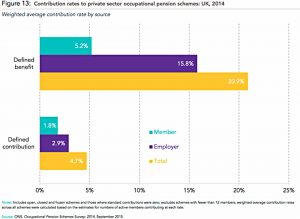

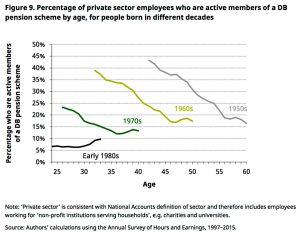

The main cause of the lack of wealth amongst the young is the death of the defined benefits pension.

- DB schemes require contributions equivalent to 21% of annual salary.

- DC schemes receive less than 5% pa.

Back in the 1960s and 1970s, 40% of private sector workers were in a DB pension.

- Now it’s less than 10%.

What we need is a compulsory workplace pension that takes in 20% of salary, like they have in Australia.

- The current auto-enrolment scheme is voluntary (opt-out) and takes in only 3% pa, rising to 8% in due course.

What we don’t need – contrary to what a lot of people are saying – is a house price crash.

- That would be massively disruptive to an economy in the process of digesting Brexit.

Things are no longer good for the young, but it’s not a simple “us and them”.

- Those born in the 1940s and 1950s had the best of things.

- Two thirds of the increase in wealth since 2008 has gone to those born before 1952.

Every decade since the 1950s sees a decline in wealth, particularly for those on middle incomes.

Those born in the 1980s have had wealthier childhoods than those of us born in the 1960s, but they will struggle to have wealthier retirements.

- Unfortunately, the resentment seems to work in both directions.

But there’s no intergenerational robbery, in the same way that young weren’t stealing from the old when things were improving decade after decade until very recently.

Until next time.