Weekly Roundup, 2nd June 2015

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup with Merryn’s column in the FT.

Contents

Advice to the young

Merryn is part of the Speakers in Schools programme, telling secondary school pupils about money. She began with the chessboard / grains of sand story to illustrate compounding.

If you put one grain on the first square of a chessboard, then two on the second, and so on, by the time you get to the 64th and final square, it’s enough rice to cover India. Now, 100% growth rates are difficult to come by in the real world, but you get the picture.

Merryn used to make the reverse point about the dangers of negative compounding on debt interest. Her message was avoid debt, save early and often and let compounding do the work. But now she has a new message: work 16 hours a week, borrow money to buy a house, and find a rich old relative to be nice to.

The first part I understand – our skewed benefits system, instead of awarding welfare pro-rata, gives full in-work benefits to anyone working 16 hours per week. No surprisingly, the average number of hours worked part time since 2012 has been 16.1.

The housing part is less clear – Merryn conflates lack of CGT on the family home with interest tax relief on buy-to-let as a reason to get into housing. We reported a couple of weeks ago on the arguments for getting rid of the debt subsidy, but that’s not specific to housing. It would need to apply to all businesses. ((Whether you see buy-to-let as a business is up to you, but for me, if there’s capital at risk it’s a business; if all you have to do is turn up for work, it’s a job))

Merryn’s regular complaints about CGT protection on homes baffle me. ((CGT is payable on buy-to-let, and on second homes)) The more we can do to encourage each family to buy one property, the better. If you had to pay CGT every time you sold your house, no-one would ever move. Isn’t 8% stamp duty enough of a disincentive?

The third leg of the stool – be nice to grandma – is about inheritance tax. The Tories are proposing to boost the allowance so that a couple can pass on £1M betweeen them. You can also now pass on your SIPP, which with the lifetime allowance coming down every other year, will soon be capped at another £1M. ((Older people may have much larger protected pots; it’s also worth pointing out that a £1M pension pot would produce an annual income of less than £29K at age 55))

I can’t get too excited about this, either. I should point out that I have no children, and so this is not a big deal for me personally – I hope to have spent all the money by then.

A £1M allowance is clearly inadequate in London – most family homes will still have to be sold to pay tax. And passing down the pension is not at odds with the philosophy behind the scheme – you get tax relief on the way in, and pay the tax when you spend the pension. Whether it’s me doing the spending or my (hypothetical) grandchildren should make no difference.

I realise that there are few targets other than the old and prudent who can be fleeced to make the books balance, but I do wish that commentators would stop banging on. Perhaps we should all just spend a bit less. Living within your means I think they call it.

Fossil fuels divestment

John Authers wrote about the wave of fossil fuels divestment by investment funds. The latest announcement was that the Norwegian sovereign fund was getting out of coal. Universities and churches are doing the same.

John quotes the Global Sustainable Investment Alliance (probably not an unbiased source) as saying that 61% of institutional assets now have some kind of ethical or environment restrictions placed around them.

Boycotts of alcohol and tobacco have had little financial effect. Tobacco has been the best-performing sector in the US since 1900; in the UK it was alcohol. The reason is simple – when some people won’t invest, stocks become cheaper for those who will.

MSCI now has a low carbon index which holds all the same stocks as its all world index, but weights them according to their carbon footprint. This index comes within 0.3% of the “true” index, with an 80% reduction in carbon footprint. But will an 80% reduction satisfy the divesters?

Chinese currency valuations

Izabella Kaminska took a look at the valuation of the Chinese currency. The IMF has just announced that the remnimbi is “no longer undervalued”.

The evidence for the previous undervaluation was the large current account surplus (ie. cheaper exports) and the buildup of FX reserves (better to hold on to them if your currency will be going down against them) – what is termed the “external position”.

The perceived risk with the previous situation was that China might cause a run on the dollar by selling some of its reserves. But that would now work against China, as the value of the remaining reserves would go down.

The big change has been the QE from the US, which has created downward pressure on the dollar. China has not responded and its current account surplus has fallen. The rate of FX buildup has also slowed.

The IMF’s announcement means that the remnimbi is eligible for “Special Drawing Rights” (SDRs). SDRs are derived from the “bancor”, a supra-national currency suggested by Keynes at Bretton Wood in 1944.

At the time the conference decided on a fixed-rate exchange machanism tied to gold, but in 1969 SDRs were introduced to replace gold. The idea was that SDRs should expand with world trade.

SDRs are currently based on the dollar, the yen, the euro and the pound, but China wants in. It would then be able to settle trade debts in its own currency.

The Economist also looked at the rise of the Chinese currency, which they called the yuan. ((Both names are good. Renminbi is the official name and means “the people’s currency”. Yuan – the Chinese word for the Spanish silver dollar or “piece of eight” – is the name of a unit of the renminbi currency. Things cost one yuan or 10 yuan, not 10 renminbi. It’s similar to the distinction between “pound sterling” and pound – things don’t cost 10 sterling. In fact Chinese people call the currency “kuai” or “piece”, something similar to quid in the UK and buck in the US.))

US Treasury Secretary Jack Lew still sees the yuan as undervalued and US senators have passed a bill allowing sanctions (eg. import duties) against countries deemed to be manipulating their currencies.

In recent months China has been propping up the yuan against the buoyant dollar, perhaps in the hope of joining the SDR system. Would the US senators support Chinese subsidies to help their exporters who are harmed by this policy?

North Sea oil

The Economist also reported on the threatened future of North Sea oil. During the boom times, inefficiencies were ignored, and it may now be too late to fix them.

The industry faces four issues:

- the low oil price

- high costs

- ageing infrastructure

- a bill for billions of dollars to decommission old platforms

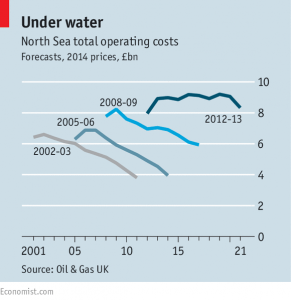

The risk is that as a few unprofitable companies shut down, the bill for the shared pipelines and terminals falls on those who are left. Expenses have doubled in the last 15 years, of which only 20% is due to increased activity.

Bad planning and bespoke parts are to blame according to McKinsey, as is reliability – offshore installations are online only 60% of the time. The main industry body, Oil & Gas UK has repeatedly forecast falling costs, just before they have risen.

Even at $100 a barrel, an eight of production was loss-making. At $55 in March, only half was profitable.

Lean production techniques, borrowed from car manufacture and used by firms such as Aera in California, are less applicable offshore. Nevertheless, production in the Gulf of Mexico is more efficient than in the North Sea, as is that in Norway.

With 40 years of production still in the ground, the predicted withdrawal of the oil majors could lead to opportunities for smaller players. But a more collaborative approach between the industry and the government will be needed. There could also be tax breaks to tempt private equity firms. Watch this space.

Forestry investment

The newspaper also reported on what a good investment forestry has been. Forests returned 18.4% last year and have averaged 21% since 2010. The FTSE-100 returned 7.7% and commercial property 10.9% over the same period.

There are decent tax breaks also: no capital gains and no income tax, plus no inheritance tax (like farmland).

Timber prices are up, but that only accounts for roughly 3% a year. Most of the rise is in the land value. Biomass boilers using wood offcuts are also helping.

Future demand is expected to be good, as the UK is short of trees and imports more than half its timber.

Political bluffing as option writing

Does Greece really want to default and leave the Euro? Does the UK want to leave the EU? The Economist reported on political bluffing.

If the countries’ leaders are bluffing, it is like them writing (selling) an option. The premium is the political popularity they receive at home from standing firm against foreigners.

The problem with writing options is that the people who bought them are the ones who decide whether they will be exercised. If they are taken up, it won’t be at a time which is good for the writer.

For Greece, the “owners” of the options are principally the EU; for David Cameron, the UK electorate (literally) gets a vote, too. Plus it’s possible that an EU referendum in the UK could be subverted into a mid-election protest vote.

The advantage that the option writers have is that the price of exercising the option – ideally, the “profit” from the exercise to the owners – cannot readily be calculated in advance, which makes it less likely that it will happen.

But the harder they press their case, the greater the potential profit. And in Britain’s case, underplaying their hand makes it more likely that the referendum will go against the government.

Beyond these specifics, politicians are in general now bluffing when they make short term promises, since the important short-term drivers of growth (the oil price, US interest rates, China) are outside their control.

Productivity

The newspaper also looked in detail at the UK’s flat-lining productivity and found that some industries are doing much better than others.

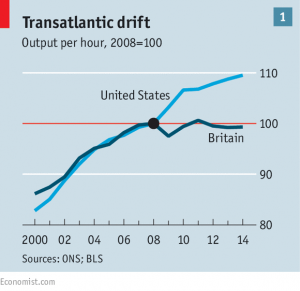

Though the UK economy is now a world leader in terms of growth, and employment has never been higher, GDP per hour worked remains lower than 2007. The US is now 9% up on 2007 productivity, and even France is up 2%. The G7 average is an increase of 5% since 2008.

In the 2008 recession, UK firms decided to hang on to staff to save the expense of re-hiring later. Producing less with same people means a productivity drop. With the recovery to 2011, output per hour recovered as expected.

Then, instead of squeezing more from existing workers, companies started to hire again – 1.3M jobs were added between 2010 and 2014.

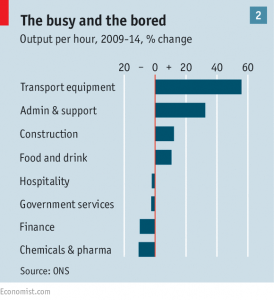

Transport manufacturers (cars, planes, trains) have done best, up 56% since 2009, benefitting from investment in technology, and supply chain management. Links between universities and industry have been crucial. Admin and support has also done well.

Finance and insurance is down 10%, partly reflecting the (artificially) high productivity before the crash, and also due to increased regulation. ((It’s worth noting that even after this fall, finance is more productive than manufacturing; there’s no evidence for a shift away from the service economy))

Chemicals and pharmaceuticals have done even worse, and the decline of North Sea oil (see above) will have a negative effect moving forward.

Lack of investment seems to be part of the problem. Lending and investment are both down, as cheap workers seem to have been preferred to expensive equipment.

There are a few areas where policy changes could help:

- Industrial clusters should be encouraged, since hubs are good at attracting talent and money. Cambridge’s experience with pharma startups is a good example.

- Lighter planning would also be a good idea: Oxford’s life-sciences firms are strangled by a green belt.

- Social housing could be re-prioritised for workers, so they can move to where the work is,

- Tax credits for less productive part-time jobs (see above) could be cut back.

Something needs to change.

Basic Income again

We reported last week that the Economist had worked out that basic income was too expensive to implement. In the Huffington Post last week, Scott Santens – a basic income advocate and reddit moderator – argued that the Economist had got its sums wrong.

The basic Economist position is:

- tax equivalent to 25% of GDP is needed for education, police and infrastructure

- a basic income means more tax on top of that – a basic income of 20% of the median income needs taxes of 20% on top of the original 25%

- to get rid of “relative poverty” (ie. pay out 60% of the median to all) needs taxes of 60% on top, ie. 85% in total

Ignoring issues like the modern-day applicability of Tobin’s 50-year-old equation, at first glance the maths seems reasonable – if the median income is, say £20K, and we want to give everyone £12K then on average we’ll need to take £12K from everyone.

The people at the top will pay more than those at the bottom, and of course everyone gets £12K back, so the net effects vary widely, but the 60% average initial hit doesn’t seem wrong:

- someone on the minimum wage of £12K would lose £7.2K and gain £12K = net gain £4.8K

- someone on the median salary of £2oK would lose £12K and gain £12K = net gain £0

- someone on the average (mean) salary of around £26K would lose £15.6K and gain £12K = net loss of £3.6K

- someone on £50K would lose £30K and gain £12K = net loss of £18K

- someone on £100K would lose £60K and gain £12K = net loss of £48K

And so on. In practice, all these salaries would adjust to the new world of a basic income, and we would probably scrap the personal allowance against income tax, ((This would in effect equate to an extra loss of £2K for everyone earning more than £10.6K)) but for the purposes of checking the maths, it’s ok.

Note that this is not an easy system to sell to the population – everyone from around £15K pa loses out. But it is an oversimplification.

Scott’s first point concerns income skew. The mean salary is a lot lower than the average (£20K vs £26K in the hypothetical example above).

Scott uses 2010 data from the US to suggest with a top-down analysis that a 36% tax could fund $12K per adult and $4K per child. I’m not certain that income level equates to the relative poverty measure used by the Economist, and it’s considerably lower than the basic income needed to live independently in the UK.

Scott’s second point is that lots of government spending can be eliminated through basic income. This is clearly the case, and in my straw man above it would mean a reduction in the initial income tax rates (ie. a further rebate, especially to those on higher incomes).

The third issue is that in the US there are lots of available tax deductions (eg. mortgage interest) and these “transfers” as he calls them can be eliminated. This is probably less important in the UK.

Scott estimates that by eliminating government spending and tax code transfers, the additional tax rate needed for his version of basic income is only 18%.

Scott sees basic income as a tax rebate for most of the US population, with the burden of funding it falling on the top 20% (or possibly an even smaller proportion of society).

This is a fascinating debate – if it can be demonstrated that basic income is affordable then the main objection to its implementation has been removed.

For me, there’s still a whiff of the perpetual motion machine about the idea that you can conjure money out of the air, give it to everyone and make life happier. If it were that simple, the SNP would have done it years ago.

When I have a bit more time I will carry out a similar calculation to Scott’s using UK data. I expect the results to be somewhere between the Economist’s 60% and Scott’s 18%. In the meantime, I’ll be looking for a response from the Economist.

Until next time.