Weekly Roundup, 4th March 2015

We begin today’s weekly roundup as usual in the FT.

Contents

FTSE-100 all-time high

In fact, we begin where we left off last week, with the FTSE-100 hitting record highs.

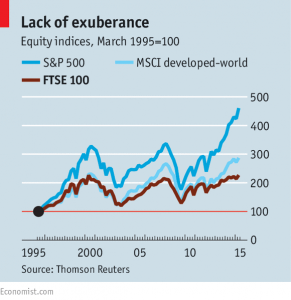

Judith Evans’ Chart that tells a story was a graph of the FTSE-100 against the other UK indices. The first thing to point out that although the headline index looks flat over fifteen years, it’s actually kicked out 3% of dividends each year, so in reality you would be around 50% richer (before inflation) by holding it.

In real terms the index remains 28% below the previous high. In nominal terms, it has almost doubles since the March 2009 low.

The second point is that the small cap index went up by 46% (excluding dividends) and the FTSE 250 by 167%. The explanation is that the FTSE-100 in 1999 was distorted by dot-com stocks. The PE ratio today is 50% lower and only around half of the 1999 stocks remain in the index.

It’s still an unrepresentative index though, with lots of very international stocks, and a high weighting to resources stocks and to finance. The FTSE-250 is much more UK-based and diversified.

The Economist chose to focus on comparators, noting that UK government bonds had returned a real 67% over the period, compared to 13% from equities. The outperformance is unlikely to continue. The yield on 10-year bonds is now 1.8% compared to 3.4% on the index. The FTSE has also trailed the World Index, and in particular the US one.

Common sense on annuities

Bear with me readers, as I return once more to the subject of annuities. Jonathan Eley’s column this week was a welcome change – a balanced assessment of their role in the pensions solution.

Annuities remain bad value, but at the same time, longevity risk and sequencing risk are real. The product also faces a hard sell at the moment: bond yields are historically low and lots of savers will soon be getting their hands on their pension pots for the first time in 30 years. They are hardly likely to want to hand the cash straight to an insurance company.

Jonathan reports on the experience from the US. In the initial years of retirement, spending on Harley-Davidsons and cruises is high. As health declines, spending tails off. By 80, retirees don’t spend much and don’t want to manage their own investments any more. This is where the annuity comes in.

So what we need is a product to bridge the gap from 55 to 75 or 80. In the US this takes the form of income funds benchmarked to an index which tracks the cost of buying the annuity in the future. Sadly they come with no guarantee of matching the index. ((They also aren’t available in the UK at the moment))

This feels like a role for the government to me. Such a product would be a great improvement on the recent granny bonds.

Property crowdfunding

Merryn’s column took a look at property crowdfunding. Property in the UK (especially the south) is expensive, but people still want to buy more, either to live in or as an investment. Buy-to-let is time-consuming and you need to scrape a 25% deposit together. And it offers little diversification.

Which is where property crowdfunding comes in. Think buy-to-let crossed with P2P. The main platforms are PropertyMoose, The House Crowd and Property Partner. You buy a house with a bunch of strangers, inside a limited company.

This is a seriously bad idea. You don’t choose the tenants or set the rent and you aren’t in charge of the management costs. If the revenue doesn’t cover the costs, the platform will borrow against the property, reducing its value.

It’s expensive (5% up front, 15% to 25% of the rent) and illiquid (for you to sell, someone needs to buy). Some schemes will rely on an exit vote every five years. If a secondary market arises, it’s likely to be populated by vultures looking to prey on distressed sellers. And the liquidation process for a failed platform would be a nightmare.

What we need instead are listed products that invest in regional residential property. Either ETFs or investment trusts would do, but I don’t know of any. There is one open-ended fund from Hearthstone, but it’s not regional and I don’t know what the track record is like.

Labour’s pension plans

Josephine Cumbo reported on Labour’s plans to reduce student tuition fees by diverting money from pension tax reliefs. They would reduce the lifetime limit from £1.25M to £1M and the annual contribution limit from £40K to £30K. (There are other planned restrictions aimed at very high earners.)

Apart from the bad politics ((Students want the fees abolished rather than reduced, and most of the benefit will accrue to higher earners who actually repay their loans – see this Economist article for more on why this is not a progressive idea)) there are two points here:

- a £1M DC pot allows safe withdrawal of £35K to £40K per year, which is below the inflation-withered higher rate tax limit ((Interestingly, because of the favourable treatment of DB pension calculations, a £1M limit will support a £50K DB pension))

- £30K per year means that people who start to contribute in their late 30s or 40s will never get to the £1M limit anyway; this is somewhat offset by the ability to save another £15K per year into an ISA

The lifetime limit seems destined to suffer the death of a thousand cuts. Back in 2012 the limit was £1.8M so Labour propose to almost half it in four years. Politicians of all hues seem determined to wean us off tax-relieved pensions and into the less favourable ISA.

P2P ISA limits

Judith also reported on plans by Zopa to impose temporary lending limits on ISA investors. Although P2P lending hit £1bn last year, more than half of Britons have not heard of it. ISA eligibility is likely to change that next year.

Giles Andrews, head of Zopa said “That’s going to be a challenge for the industry.” As well as the scale of the new influx, its lumpiness will be a problem. Most ISA money arrives just before the April 5 tax year deadline, whereas loans are spread through the year.

Simple limits per investor are unlikely to do the trick unless they are set very low, as most investors should prefer to spread the risk by using competitor platforms (RateSetter, Funding Circle and proposed new entrant Hargreaves Lansdown).

Rhydian Lewis of RateSetter said: “Surplus lender funds stimulate more competitive rates for borrowers, increasing the number of borrowers seeking capital”. Cormac Leech of Liberum pointed out the potential for a “wall of ISA money” to “collapse” returns.

Perhaps the long-awaited (10 years since Zopa launched) P2P inclusion in ISAs will be a damp squib after all. Regular investment through the tax year may well be required.

Redwood ETF portfolio

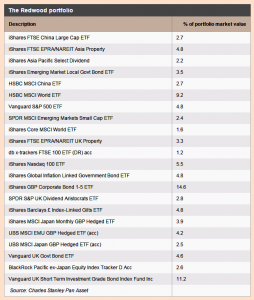

John Redwood provided his regular update on his passive ETF portfolio. He has cut US exposure after a good run and is increasing exposure to Europe because it is doing badly. ECB QE is another factor.

Renewables

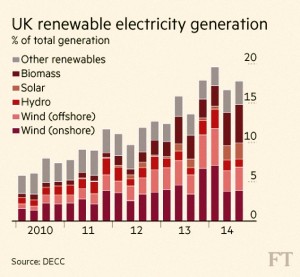

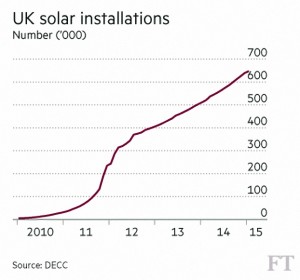

The FT also had a special report on renewables, which have grown to 18% of UK electricity generation, from 3% back in 2003. This is on the back of significant subsidies for solar and wind, typically around 50% of a scheme’s income.

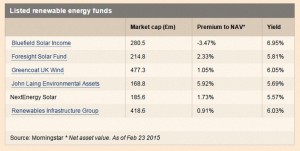

The simplest way to invest ((Apart from putting solar panels on your roof – this costs between £5K and £8K and has a ten-year pay-back period)) is via investment trusts. Renewable ITs raised £773M in 2014, up from £93M in 2013. The six available trusts yield around 6% and mostly trade at slight premiums to their NAV. Gearing levels vary, with Foresight and Greencoat at the lower end.

The subsidy regime is due to change in 2017 and returns are likely to fall, though their predictability should improve. This could be offset in part of whole by pending technological improvements in solar panels and reductions in installation costs.

EIS and VCT had also been big players in renewables, but solar was excluded in 2014’s Budget. Hydroelectricity and anaerobic digestion have since been added to the list of ineligible projects, with effect from April. Foresight, Octopus and Triple Point have schemes that are open until then.

There are also P2P lending and equity crowdfunding options available, though these are difficult to recommend given the risks. For those who are interested, Trillion Fund and Triodos Renewables offer equity opportunities, while Abundance Generation offers debentures (bonds).

Accounting for intangibles

Finally in the FT, Gillian Tett’s column was about accounting for intangibles. Australian business writer Jane Gleeson-White has written a book called Six Capitals, or Can Accountants Save the planet.

Double-entry accounting as invented in 15th-century Venice has coped well with manufacturing in the industrial age but deals badly with the intangibles of the digital age (ideas and networks for example). Externalities (costs that cross system boundaries such as environmental problems) are also an issue.

Gleeson-White argues that the definition of capital needs to be extended to include things like human capital (future potential), social capital and environmental capital. She quotes Indian research showing that the true costs of a $4 burger is $200, and the National Audit Office assessment that bees are worth £200M to the British economy.

I’m quite the fan of this approach, though I see it from the opposite direction. Without converting every factor involved into a currency equivalent, how can you make the right decisions? I also think that this broad approach would encourage more long-term thinking. The opposite is at the heart of most issues we face today.

Pensioner benefits

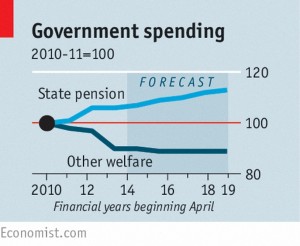

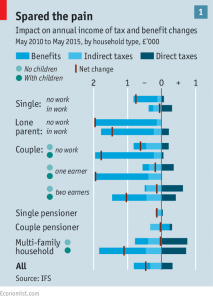

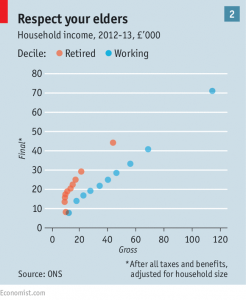

As a practical example of this broad-brush, intangible thinking, consider the calls from the Economist to scrap and or means-test benefits for pensioners. ((The Economist has previous on attacking pensioners, as do I on defending them)) The pension is increasing as a share of welfare, but this is because people are living longer and pensioners are increasing in number.

If the pension seems generous that is an illusion born of comparison with recent even meaner years. The minimum wage is £12K pa and the cap on benefits for the non-working is £26K pa. The new pension regime will come in at £7.5K pa. I know where I would be looking to make savings.

The newspaper wishes to remove or means-test free TV licences, winter fuel bills and free bus passes. They do not approve of pensioner bonds. They are envious of DB pensions and expensive houses. They wish to means-test the state pension.

Yet as the paper itself states “transfers from you to old can be justified, both because many of the old cannot work and because technological progress mean youngsters are likely to end up better off than their grandparents.” The author of the newspaper’s articles may be young, but one day they will be old. Let us hope that there are nicer journalists by then.

Applying Gleeson-White’s approach:

- The young have oodles of human and social capital, which the old do not

- Well-off pensioners have deferred consumption from their youth in exchange for a more comfortable old-age; this is to be celebrated – they should not be denied because circumstances have changed for a subsequent generation

Decision-making involves risk. Those who correctly evaluate the situation should not be punished later because they have got things right.

We would be better off providing the opportunities and skills to allow that minority of the young willing and able to do so to exploit their human capital (convert it into actual capital) than stealing from those who have already achieved this.

The Economist accuses David Cameron of bribing the old. I accuse the newspaper of picking on the defenseless. Except they are not defenceless, because they can and will vote. And that is why the newspaper will not get its wish.

Until next time.