Weekly Roundup, 16th February 2016

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with the Chart That Tells A Story. The big stories of the past week were the worries over banks and the bear market.

Contents

Banks and the FTSE

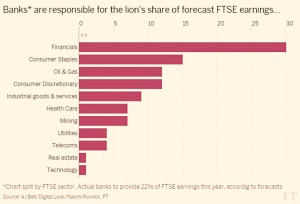

Naomi Rovnick combined the two by looking at how bank stocks drag on the FTSE-100 index.

Last week the FTSE was down 9% in 2016, at close to 5,500. ((Admittedly, we are up more than 5% over the past three days, so the bear is not so much in focus this week ))

- Much of the early focus was mining and oil groups, with big losses and dividends cuts across the sectors.

- But the banks have also slumped badly: HSBC is down 18%, Lloyds 27% and Barclays 29%.

There are two worries:

- future earnings in a low or even negative interest-rate world (low interest rates squeeze bank margins between the rates they borrow at and lend at)

- capital strength if earnings are squeezed

This is also a worry for dividend investors – with resources firms out of the picture, banks and other financials are a key source of income.

- they contribute 30% of FTSE-100 profits

- they are expected to provided 48% of dividend growth for 2016

Which means that the FTSE could be vulnerable to earnings shocks and dividend cuts as the banks report their results from later this month.

UK banks remain profitable, and 2016 should see the highest aggregate profits since 2007.

- At the same time, they are trading at valuation multiples as low as in 2008, so something doesn’t add up.

But if negative interest rate and falling bank profits fail to arrive, UK banks are looking pretty cheap at the moment.

Deutsche bank

Outside the UK, Deutsche Bank has been the main focus of the worries.

- Its CEO was forced to reassure staff in an internal memo that the bank was not about to collapse.

- Later the German finance minister chipped in, to no great effect.

In the wake of Deutsche’s £5bn loss and suspended dividend for 2015, investors are concerned about interest payments on “contingent convertible bonds” (cocos) – an instrument ironically chosen in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis to act as a buffer in future emergencies.

Deutsche’s illiquid cocos fell to 70 cents on the dollar.

The Economist had an article looking at cocos in more detail.

- Cocos are bonds that turn into equity when times get bad.

- Government and central banks like them because they “bail-in” the bondholders of a bank in trouble, unlike the 2008 crisis, when equity holders alone took the hit.

- Until the bank needs the extra capital, they behave like bonds, sparing the existing shareholders from dilution.

- If things do get bad, the interest payments (often 6% to 7% pa) can be suspended, the bond can be converted into equity, or even in extremis, can be written off entirely

The problem seems to be that the cocos aren’t working as expected. Deutsche has a decently large capital cushion for a bank, at 11%.

- But its lack of profitability means that it may not have the required “available distributable items” (ADI) from which to pay the coupon on the cocos.

So an instrument designed to level the playing field between holders of equity and debt may end up punishing them both too soon.

European banks

The newspaper also had another couple of articles on European banks (1 and 2).

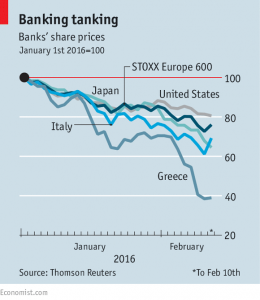

- As well as the fall in UK banks shares and Desutche’s problems, American banks are down by 19% in 2016, and European and ones by 24%.

- Japanese banks are down by 36%, Italian ones by 31% and Greek banks by 60%.

- Prices of credit default swaps are up.

- We’re back to the lows of 2012, when a euro breakup looked likely.

But this is not 2008.

- Banks are better capitalised – up from 9% in Europe in 2009 to 12.5% now.

- The cost cutting at Deutsche and Credit Suisse – two of the worst affected banks at the moment, should lead to slimmer, safer, more profitable firms.

The problem is the global economy.

- In general banks do well when the economy does well – China, commodities and oil are weighing heavily.

- Interest rates look as though they will stay lower for longer, and bank margins with them.

The Economist is most worried about Italy, where non-performing loans are 18% of total bank lending.

- In continental Europe, retail investors hold bank debt – €200bn of it in Italy, equal to 12% of GDP.

- Bailing them – and bank depositors with balances of more than €100K – into a new banking crisis would be politically difficult.

And the EU would classify government purchases of the bad debts as illegal “state aid”.

- So there is no easy way out.

Who killed the bull?

Back in the FT, John Authers looked at who killed the bull market. Like the Murder on the Orient Express, he came up with a dozen suspects, all partially to blame.

- Opec – who refused to limit the supply of oil, causing the price to crash

- for consumers and importers, this is good news

- but for exporters, and especially the US economy, the short term impacts are negative

- Sovereign wealth funds – SWFs are mostly full of petro-dollars, and the oil price decline means that many have started to shrink

- the easiest assets to sell would be Japanese and US stocks

- China’s stock market

- The Chinese currency – are they devaluing too quickly?

- The Fed – having waited too long to start raising rates, December’s hike now looks badly timed

- US corporate earnings – the S&P 500 is expected to earn 4.1% less in 4Q2015, and forecasts for 2016 are falling.

- Negative interest rates – in Japan, the Euro zone and Sweden have been seen as the kiss of death for bank profits

- and does this mean the central banks are out of ammunition?

- I don’t think so – some kind of helicopter money can’t be far away

- US recession – this looked very unlikely only a few weeks ago, but some weak numbers have got people thinking “maybe, just maybe”

- Bond market – John says the flattening yield curve (reduced premium for holding longer-term bonds) is a classic recession signal.

- Irrational exuberance – the long US bull market has been defended by some because of a lack of enthusiasm

- bull markets normally end with a “blow-off” fuelled by euphoria, which we haven’t seen this time

- but valuation measures are stretched nevertheless (in the US, but not in Europe or emerging markets)

- Dodd-Frank – regulation has made banks unwilling to gamble by making markets in bonds

- this lack of liquidity increases volatility

- The voting public – the popularity of Trump, Sanders and Cruz in the states, and the fear of Brexit or worse in Europe has unnerved the markets

John also points out that short sellers, Syria and Greece are not to blame this time. And there have been few recent calls for government-backed infrastructure stimulus.

Five bear markets compared

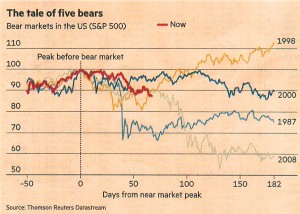

Also in the FT, the Lex column compared the five most recent US bear markets (now, 2008, 2000, 1998, 1987). As luck would have it, these are the five that I remember.

Their first point is that today hardly counts – the S&P 500 is only down 13% (though we did hit genuine bear territory here in the UK).

In the other four cases, central bank action was key to what happened next.

- In 1987, 1998 and 2000, the Fed took immediate steps to restore confidence.

- In 2008 the monetary easing took to long to work, and we had a full-blown economic crisis by the end of the year.

Here’s hoping that we see some kind of action from the Fed in the next few months.

Passive investors and bear markets

In the last of the glut of articles about banks and bear markets, Ken Fisher looked at whether passive investing really works for private investors.

In theory passive investing is a great idea.

- investment funds underperform the market as a whole, because of their costs and fees

- passive funds have lower costs and fees than active funds

- so passive funds should gradually out-perform

And so they appear to do. But:

- only over the long-term

- only if you stick with them for the long-term, or as Ken puts it, if you “hold your nerve”

Private investors have a terrible track record for leaving things alone.

- They buy at the top and sell at the bottom, under-performing indices by around 3% to 4% a year.

- $13bn left US equity ETFs during January.

- The best performing private investor accounts at most brokers are famously the one held by people who have died.

To reap the benefits of passive investing, you need to tune out from the media’s reporting of panic, and avoid at all costs selling out at the bottom.

- For most people, that’s very hard to do.

And if you fail, you aren’t being passive any more.

- You’re timing the market like everybody else.

I wouldn’t call myself a passive investor – I like to blend passive and active funds with directly held UK stocks.

- But I am pretty good at doing nothing.

That’s partly because I’m lazy, and partly because I have a bad track record of spotting bear markets in advance.

- I didn’t see 1987 coming, or 1998, or 2008.

- The only time I did call it right was the dot-com crash in 2000.

- I was very actively trading a large portfolio (for me) during the last year of that bull market, and when I started losing money I sold everything within a couple of weeks.

But usually by the time I notice things have gone bad we are already down 15% or 20% from the peak, and it seems too late to me to start hedging.

- I just hold on until things recover.

This is not always easy – it certainly wasn’t in 2009 – but it’s worked out okay over the past 30 years.

- I’ll be interested to see if I can hold my nerve as I move from the accumulation phase into decumulation.

- I’ve already increased my cash holdings so that I won’t be a forced seller over a few bad years.

So Ken isn’t really aiming his column at me.

- He’s talking to all you non-robots out there.

And of course, Ken runs an investment firm, and generates his living from advising and managing funds for active investors.

UK tax code

The Economist looked at George Osborne’s failure to simplify the UK tax code – as he promised when in Opposition.

- He did set up the Office of Tax Simplification (OTS) in 2010, but not many of the 1,042 reliefs identified by the OTS have been simplified away.

- The newspaper notes the decline of relief on the first 15p per day of “luncheon vouchers”, but also the introduction of many new reliefs.

- By March 2015, the OTS found there were now 1,156, and the tax code was a third longer than when the OTS was founded.

- The burden on UK companies has remained stable – and low by international standards – at 100 hours of form-filling per year.

Some of these are not really loopholes

- the personal income tax allowance is a good and progressive tax policy, expressed as a relief.

These “good reliefs” are really disguised public spending, designed to “promote economic and social objectives”.

- For example, some form of pensions tax relief is probably a good idea, even if people can argue over the details.

The problem with having so many reliefs is that they encourage tax avoidance.

- Of course in a sense that’s what they are supposed to do.

- The real question is whether the pubic benefit is obvious to all.

But this is a severe test, which few areas of public spending could survive.

- We start by looking at whether we need a UK film industry (£2bn of support over the 9 years to 2015).

- Soon we are considering how big the BBC should be.

- From there it’s not that great a leap to how big should the NHS be.

A good tax relief is in the eye of the beholder, but it would be nice to see the list getting shorter at least.

- Alas politics – and the need to regularly pull a populist rabbit from a hat – means that this is unlikely to happen.

Why central banks change rates

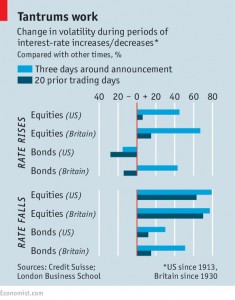

Finally, Buttonwood looked at what makes central banks change interest rates.

- Officially, they are targeting inflation (and sometimes GDP or unemployment).

- But really – at least since the late 1980s – they have seemed to target asset prices.

Under Alan Greenspan, the Fed began to cut interest rates when stocks fell (the “Greenspan put”).

- The link became even more clear when QE was introduced.

The annual Global Investment Returns Yearbook from BS and Credit Suisse shows that markets do better when rates are falling:

- US stocks returned 9.3% real pa since 1913 when rates were falling, against 2.3% pa when rates were tightening).

- Bonds also do better (3.6% pa vs 0.3%).

- Houses, art and gold also do better when rates were falling.

So far so expected.

But looking the other way, the chart shows volatility changes in markets before and after rate increases and cuts.

- Stock markets (and the UK bond market) are more volatile after a rise, but not before it.

- But the markets are as volatile before a rate cut as afterwards.

This suggests that central banks wait for calm before a rate rise, but respond to high volatility with rate cuts.

- In other words, they listen to the markets.

Until next time.

Mike,

I would like to congratulate you on your newsletter, that is, educational & informative.

I read from a variety of sources including the USA.

And I thought I would provide my personal feedback and say – keep it up.

I would also recommend your newsletter it to other people.

Best Wishes, Rajan

Thanks Rajan, glad you get something out of it.