Weekly Roundup, 31st October 2017

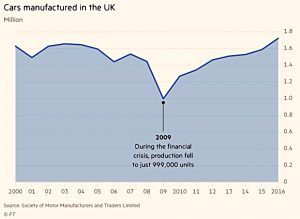

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with the Chart That Tells A Story. This week it was about car-making in the UK.

Contents

UK car-making

Ed Bowsher looked at UK car production since 2000.

- Production fell after the MG Rover collapse and during a period of sterling strength.

- It fell much further after the financial crisis.

But things have recovered and last year was the highest production of the 21st century.

Production was even higher back in the 1970s, and the proportion of foreign parts (now 60%) was lower.

The rest of the article was mostly speculation about the likely impact of Brexit, with the usual emphasis on the downside.

- Ed also talked about the move to driverless and electric vehicles, but worried that the necessary investment would not be forthcoming post-Brexit.

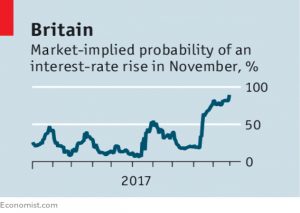

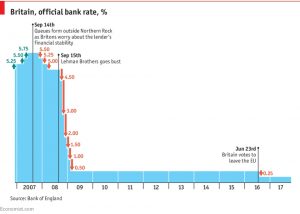

Interest rate rises

The Economist had a couple of articles about the likely UK interest rate rise next month (1 and 2).

- The newspaper is not in favour.

They think that the “Brexit threat” is not over and would wait until January.

- Given the state of the UK’s media, I expect the perception of a “Brexit threat” to drag on to 2019 and beyond.

More importantly, they (and I) see no signs that the UK economy is overheating.

- The current bout of inflation stems largely from the slump in sterling after the Brexit vote, and will fade naturally.

- Wage growth would be the thing to look for, at at 2% pa it remains below inflation (3% pa).

There’s also the risk that some people with mortgages won’t be able to cope.

- Household debt (including consumer credit) is now 140% of annual income, which is high compared to the historical average.

But anyone who hasn’t factored in a rise from 0.25% to 0.5% is in for a world of pain at some point in the future.

- The post-war average for UK interest rates is 6%.

A more serious issue is that raising rates would send a signal that hard times (and further rate rises) are coming, impacting consumer spending and the wider economy.

- Consumer spending accounts for 60% of UK GDP.

- And the first rate rise for more than a decade might have a disproportionate signalling effect.

It’s possible that the extra interest from savings accounts would have a counterbalancing effect.

- But savers tend to save, and are unlikely to splurge a windfall of 0.25%.

Brexit interest rate

Sticking with interest rates, Buttonwood wrote about the discount rate that will determine the size of Britain’s bill for the pensions of EU bureaucrats.

Some of these payments might still be due in 70 years from now.

- Pensions are paid as they fall due, so no assumptions about future investment returns are needed.

But to work out what sum will be involved, we do need to make assumptions about future salaries and life expectancies.

- And then this future some must be discounted using some interest rate.

The higher the rate, the lower the bill.

- So you can bet there will be an argument about it.

The EU currently has a pension liability in its accounts of €67 bn, using a discount rate of 1.7% (0.3% after inflation).

- The rate used is linked to interest rates on EU government debt.

But when calculating employee contributions, it uses a 22-year average, which includes higher rates from before 2000.

- The period used for the average is increasing from 12 years in 2012 towards 30 years by 2021.

It currently produces a nominal rate of 4.8% (3.1% after inflation).

- And while the rate used in the accounts is falling, that used for employees is rising.

Using the employee rate might save the UK half its bill, some €2.5 to €4 bn.

- Unfortunately, UK accounts for the pensions of civil servants (teachers say) also use a low discount rate.

Britain could insist on paying the actual amount due each year (as the EU does) but it would then have liabilities stretching out beyond 2070, which might not play well at home.

Binary options

The Economist also wrote about binary options.

- I’m not a fan of these products, which expire – sometimes after only a few minutes, and usually after only a single day – either in or out of the money (at 100 or 0, regardless of the purchase price).

It’s possible to imagine scenarios where they could be used for risk management, but in reality they are marketed at young and inexperienced “investors” who are more used to betting on sports.

- They are considered to be gambling in the UK so they are not FCA-regulated.

- UK firms are covered by the Gambling Commission, but foreign firms with EU passporting are not.

Interestingly, spread bet firms like IG are regulated by the FCA, even though spread bet winnings are tax-free.

As well as being risky and inappropriate for their users, binary options appear to be operated by dodgy firms who don’t let the minority or winners extract their winnings.

- In January, the FCA will take responsibility, as MIFID 2 comes into force.

It’s possible that short-term binary options will be banned.

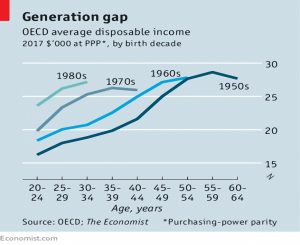

Millennials

It turns out that millennials are actually doing better than baby-boomers did at their age, in OECD countries at least.

- In fact, the gap between millennials in their early 30s and boomers at the same age is a whopping 40%.

This counters the popular impression that the greater wealth of boomers is in some way unexpected.

- Old people are richer than young people – that’s just how money and time interact.

- And the next time an old guy tells you that things were tougher in his day, you should listen.

What is just as interesting, however, is that Gen-Xers are failing to turn their early advantage into a lasting one.

- It looks as though they will fall behind the boomers by the time they are 50.

Which might mean that they are finally entitled to bemoan their lot.

Tax cuts and wages

The Economist also speculated on whether cuts to US corporate tax rates might lead to higher wages.

Trump’s government says that the proposed tax cuts will benefit the middle classes, not the rich.

- But the think tanks conclude otherwise.

The disagreement is around who benefits from cuts to corporation tax.

- Trump’s team says that these cuts will raise wages.

Left-wing economists argue that the imputed increases would cost more than the corporation tax cuts would deliver, so they are unlikely to happen.

- The right wing economists argue that it’s like the laffer curve in reverse.

Higher taxes reduce revenue, lower taxes will increase benefits by reclaiming this “deadweight loss”.

- The most likely mechanism would be increased investment leading to competition for workers and hence higher wages.

The Economist admits this is logically possible, but has its doubts:

- the deadweight loss appears to have been exaggerated

- the US has unique opportunities (eg. Silicon Valley) that mean that high corporate taxes are less likely to have driven investment abroad

- the “territorial” taxation of profits will make investment abroad more attractive than investment in the US

The most likely outcome from the corporation tax cuts is a small increase in wages, not a large one.

Binging pensioners

There’s been a bit of outrage in the press than a small minority of pensioners have been using the pension freedoms to “fund alcohol and gambling binges”.

- The complaint is that after spending their pensions, they will then fall back on the state for support.

- Submissions to the Commons work and pensions committee suggest that as many as five pensioners have done this.

There is a moral argument here, since tax relief on pension contributions is intended to encourage self-sufficiency.

- There isn’t a legal one – pensioners can spend their money on whatever they want.

But if officials deem that money has been deliberately run down to secure state help, they can refuse it.

I don’t approve of pensioners blowing their pots – it feels like welching on a deal.

- But nor do I approve of the knee-jerk reaction that the best way to deal with a few offenders is to remove the pension freedoms for everyone.

- If we head off down that route, we’ll end up banning everything.

It strikes me that there are double standards involved, not to mention a bit of envy.

- Those with little prospect of having a pot to blow themselves will obviously feel jealous.

But is the pensioners’ money, and (outside of the Daily Mail) you rarely hear the same arguments advanced towards those on welfare who blow their dole cheque on holidays, big TVs, booze and fags.

- A universal safety net is a universal safety net, and there are few who suggest that moral integrity should be taken into account across the board.

Let he who is without sin, etc.

Moneyfarm again

In my comments on MoneyFarm last week, I missed the fact that for existing investors, the £10K zero fee band has in fact been increased to £12K.

- It has been removed for new investors though, so if you aren’t already with them, don’t join now.

Twitter pics

I have eight pictures this week, after drawing a blank last week.

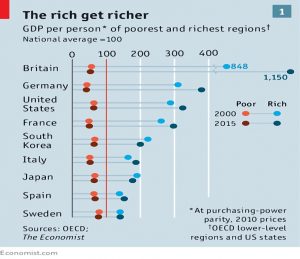

- The first three are about regional inequality, particularly in the UK.

Here are a couple of pictures that show how large London is compared to the rest of the country.

And here are the consequences (in part) – GDP per head in London is more than 10 times the UK average.

Up next is another graph showing how bull market climb a wall of worry:

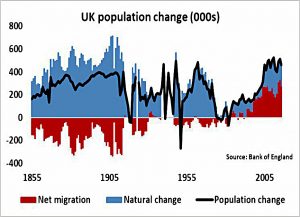

Now we have is population change in the UK:

Mass net migration into the UK is a relatively new phenomenon, only really picking up speed in the 1990s.

- Until the 80s, net emigration was much more common.

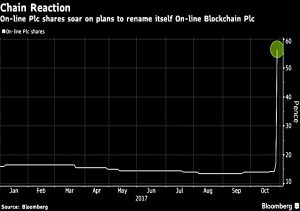

We close with three charts demonstrating the frailty and gullibility of people.

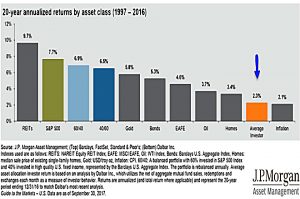

Here is the chronic underperformance of the average investor (in the US).

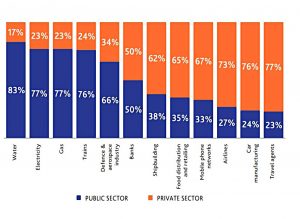

Here’s the level of support for nationalisation in the UK, by industry.

And here’s the price chart for On-Line PLC, which yesterday announced that it was changing its name to On-Line Blockchain PLC.

- Perhaps I should change the name of this blog to 7 Circles of Blockchain.

Until next time.