Weekly Roundup, 4th May 2016

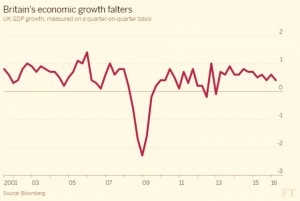

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with the Chart That Tells A Story. This week the topic was the slowing UK economy.

Contents

Slowing UK economy

Naomi Rovnick looked at the UK’s GDP figures.

- The UK grew by 0.4% in 1Q2016, compared to 0.6% in 4Q2015.

- Growth in services was down to 0.6% from 0.8%.

- Retail sales were strong, with growth of 0.8%.

The chief suspect for the slowdown is the Brexit referendum.

- Multi-national businesses could be delaying investment and hiring until the result of the vote is known.

The slowdown has not affected the pound, which reached a ten-week high after the GDP data was released.

- The lead for “Remain” in the polls seems to have caused a recovery in Sterling.

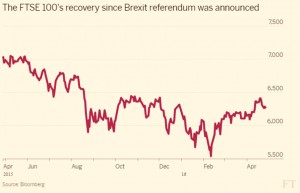

The same goes for the FTSE-100, although the constituent companies should not be especially Brexit-sensitive.

The slowdown means that interest rate increases in the UK are less likely, which should support the housing and stock markets for a little longer.

Basic Income

I managed to miss Tim Harford’s column last week, so we have two this week instead. They are at least linked.

The first is a follow-up to / repeat of his previous comments on how to deal with industrial decline (in the context of the potential closure of the Port Talbot steel works).

- He warned against governments support using taxpayer money.

- Doing nothing creates short-term losers but society should be better off.

We need to adjust to change, not resist it.

- So the answer is to support and retrain those affected, and help them to move where the new jobs are.

But it’s easier said than done.

- Industrial decline tends to affect distinct geographical areas, and house prices as well as pension pots can be affected.

It also tends to be older workers – who are more difficult to retrain and relocate – that are affected.

Tim looked at three ideas: bring new jobs to the area, help people find new jobs, and just send money.

- Regenerating affected areas hasn’t worked.

- Getting workers to move to new jobs used to work in the US, but doesn’t any more, while in Europe it used to be hopeless, but is getting slightly better.

- High housing costs in the booming areas don’t make moving easy.

The third option – just send money – was the subject of the second article.

- Tim looked at Basic Income (BI), a topic we’ve covered twice before.

It’s an interesting idea, but we concluded that it was too expensive to fund in a meaningful way.

- There are trials and pilots planned in Kenya, Canada and Finland, so perhaps we’ll have some real-world data in a few years.

Tim agrees that implementation could be more difficult than people think.

He looked at a payment of £10 a day (£3.7K pa), a little less than the proposal from the UK Green Party that we looked at a few months ago.

- That would cost £234 bn, a bit more than existing social security of £217bn.

- The corresponding numbers from the Greens’ proposal were £321 bn and £164 bn.

- The Greens would retain £67 bn of existing benefits and close the gap with £167 bn of new taxes (an increase of 25% in the tax base).

I would also point out that £3.7K pa is another “pocket-money” implementation of BI – people need more than that to survive in the UK.

- I’d prefer to see a libertarian version of BI, where the payment is twice as high but the entire welfare system (including health and education) is removed from state ownership.

Tim worries (as do I) that some people would simply stop working.

- In theory, this might reduce the tax base and the viability of the project.

- In practice, these people don’t pay much / any tax at the moment.

- Two-thirds of tax comes from higher-rate taxpayers, the top 15% (and 44% of UK working-age adults pay no tax according to Radio 4 this week).

He also agrees that £10 a day isn’t enough to live on, and so “special cases” would need to be added, making the system almost as complicated as the one it replaces.

And as we found when we looked at the Greens’ proposal, such a system needs to tax middle earners much more than at present.

- For me, that’s the real threat to the tax-base – that people on £35K to £50K stop working so hard.

Basic Income in the current economy is either expensive or mean.

- Depending on how we handle the robot revolution, we might soon have the extra money to fund something better.

30 glorious years

Both the FT and the Economist looked at the idea that markets might be coming to the end of a 30-year run of good returns.

In the FT, John Authers focused on equities. As he notes, the last 30 years haven’t felt particularly great for investors.

- From the late 80s to 2000 things were pretty good, but I’ve lived through three real crashes (1987, 2000, 2008) and the second half of those 30 years has been pretty flat here in the UK.

Yet McKinsey report that US stocks have returned 7.9% pa over the period, compared to 6.5% pa over the past 100 years.

- They are predicting only 4% pa for the next 20 years (6.5% as a best case).

European stocks have averaged 7.9% for 30 years, compared to 4.5% over the last 100 years.

- The prediction for the next 20 years is 5% pa (6% best case).

The good news from the past 30 years includes the end of the Cold War (and a reduction in defence spending), the emergence of China, and positive demographics, with baby boomers reaching peak earning and spending ages.

- Inflation has been tamed, and can’t be tamed any further.

- Interest rates can’t fall much lower (or boost asset prices much more).

- GDP growth in the US and Europe averaged 3.5% pa, but the future looks like Japan, with falling population and hence GDP.

- Corporate profits are at record highs, driven by a new global middle class, low tax rates and the arrival of the internet.

John’s main worry is pensions, both the private investors forced to rely on returns from DC schemes, and US public pensions that assume 7% pa equity returns.

- He focuses on millennials, linking their situation to the current political populism, but I think that misses the point (see below).

Buttonwood also looked at what he called “The Great Switchover“.

- Since 2009, equities have been the only game in town.

- Given the poor returns on other assets, sell-offs from bad news don’t last long.

But now the prospects are poor, McKinsey reckons that a 30-year old will have to work seven more years or save twice as hard to get the same pension as a boomer.

I disagree.

I think that twenty years of low returns would help millennials, so long as high returns came back after that.

- Someone currently aged 30 to 35 could buy a lot more cheap stocks with their monthly savings over the next 20 years, and be ready for a future boom aged 50 to 55.

Of course the good times might not come back, and in the meantime, millennials might find it hard to hold down a job good enough to allow them to save hard.

- But at least they have lots of human capital to deploy.

The people with the real problem are those aged 55 to 60 with no income other than their stock returns.

- They have to get through 20 years of retirement in a low-growth environment – right now.

BHS

The big story of the week was the collapse of BHS – a retailer with 11K staff – and the role played in its demise by its last two bosses.

- Sir Philip Green, billionaire owner of many UK shops, bought BHS for £200M in 2000, then sold the firm in 2015 for £1 to a consortium of people with little retail experience.

The death of BHS was not a surprise.

- It was the kind of old-fashioned mid-market shop you would expect to struggle against online retail and changing demographics.

The story blew up because the company’s pension scheme is in default, and the cost of bailing it out will fall to the Pension Protection Fund (PPF).

- In addition, many of the prospective pensioners face a 10% haircut to their pension.

In many of the papers, the PPF is being treated as taxpayer-funded, but it actually gets its money from a levy on corporate pension schemes.

In the FT, Neil Collins focused on the reasons behind the infamous pension deficit of £571M.

The real problem is that shares are seen as too dangerous for pension schemes, who instead load up on over-priced bonds.

- This week the UK government borrowed £4.75 bn over 49 years at 2.35% nominal, with a premium to face value that guarantees a loss to holders.

- Coupled with the low interest rates that mean that future liabilities can’t be discounted by much, and increasing life expectancies growing those future liabilities, this produces huge scheme deficits.

It also has to be asked why the pension trustees went along with the £1 sale.

- And we should probably ask the firm’s bankers why its debt was allowed to rise from £62M in 2007 to close to £1 bn when it went bust.

Questions are also being asked – for example in the Economist – about the money Green extracted from the company.

- Before 2004, BHS paid out more than £400M in dividends, mostly to Green and his wife (who lives in Monaco and doesn’t pay UK tax).

- The shop also paid rent of more than £150M to a property company owned by Green.

- And there were annual management charges of £50M pa upwards – totalling more than £600M – to Arcadia, BHS’s parent company, again owned by Green.

- Retail Acquisitions, the firm that bought BHS in 2015, also extracted £22M.

- At the same time, capital expenditure from 2001 to 2014 was £349M, less than cumulative depreciation of £438M – suggesting that the shops were being gradually run down.

Green has offered to pay £80M into the BHS pension shortfall, but the Economist wants to know:

- whether the Pensions Regulator approved a recovery scheme for the BHS pension, and

- whether the 2015 sale of BHS was cleared as not being an anti-avoidance measure

Despite the mainstream media coverage, it’s not clear that Green has done anything wrong.

Paul Scott took a look at the accounts going back to 1999, and there’s no smoking gun.

- The pension fund was in surplus until 2006, and again in 2008.

- The dividends prior to 2004 were generally covered by profits, though the total profits through Green’s tenure are less than the total dividends.

- BHS went bust owing £200M to it’s parent company, owned by Green.

- Against this, the “management” charges (actually central services charges) to Arcadia do look high.

- And Green did sell the company to an unsuitable buyer.

I’m not suggesting Green is an angel, just that the picture is more complicated than the headlines suggest.

Apple

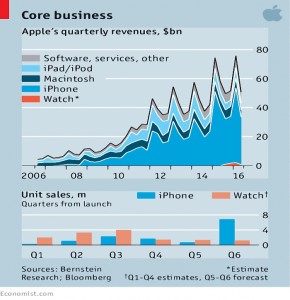

The Economist also looked at the future of Apple.

- In case you weren’t aware, the company needs another hit product.

The company has just reported its first YoY quarterly decline in revenue since 2003.

- In the meantime we’ve had the iPod and the iPhone, and for a while, the iPad.

The iWatch doesn’t seem to have made the grade – partly because of the traditional Apple high price, and partly because it needs a smart phone to work. ((That’s why I’ve stuck with my mechanical watch ))

What’s next?

- The iPhone 7 is due in September, but will it be enough?

- An Apple TV and an Apple car have also been mooted, as have devices in the connected home and augmented reality space.

But is Apple really ahead in any of these areas?

- Its big hits – the iPod, iPhone and for a few years, the iPad – came as bolts from the blue, with no competition to speak of.

Will that ever happen again?

Contractors

The Economist also wrote about the need for a third employment type – halfway between employees and freelancers – as a response to the “gig economy”.

- Uber and FedEx have been fighting claims that their contractors are really employees.

Now Uber has agreed to allow its drivers to form an “association” to negotiate with the company.

The problem arises from the monopoly power companies like Uber can exert over contractors.

- Most freelancers have multiple routes to their customers, and so more power.

- Network effects and switching costs mean this doesn’t apply in Uber’s case.

The government could just mandate that firms like Uber treat drivers as employees, but that might break the business model.

- If drivers could just drive an empty car in a quiet area for minimum wage, many would.

So perhaps a third category – with some employee rights but not others – is the best solution.

Corporate accounts

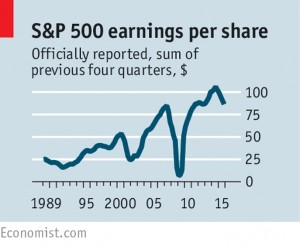

The newspaper also looked at the manipulation of corporate accounts, particularly in the US.

- The current quarter’s earnings are expected to be down 9% YoY, or down 4% excluding energy firms.

You wouldn’t know it to listen to CEOs – both IBM and Apple made bullish statements against falling earnings.

The gap between the “adjusted” earnings that firms want you to look at, and the strict accounting standards numbers is now at 20%, well above the long-term trend.

- Firms that aren’t profitable using the standards should be avoided, as should those with large gaps between standard and adjusted figures.

- Low (cash) tax payments are also a clue, as is cash flow in general.

In 2015, 232 firms in the S&P 500 had lower cash flow than adjusted profits.

London’s buildings

The Economist had two articles about London and its need to build more houses and offices.

- London’s economy grows twice as fast as the rest of the UK and it’s economy grows 50% faster.

- London is growing by 100K residents a year, but only builds 25K new homes.

- Thus the median price of a property has tripled over 20 years.

- The cost of a hectare of residential land increased by 300% in the fifteen years to 2008.

- Offices in the West End are twice as expensive as Manhattan.

For the Economist it all boils down to building on the Green Belt that surrounds the city, occupying 20% of its area.

- There are 49K acres of land within it that are not beautiful but are within 800m of a tube, train or tram station.

That’s enough room for a million new houses.

- Maybe we should build them.

Brexit

We end this week with the Economist’s Brexit briefing.

- I have found this series to be increasingly pro-Remain as the weeks have progressed

This week there were two articles.

- The first looked at the effect of Brexit on the EU.

The timing of the referendum is bad from the EU’s point of view:

- the euro crisis rumbles on

- growth is slow

- youth unemployment is high

- Greece is in trouble

- there’s a refugee crisis

And there would be direct impacts from Brexit:

- the UK has diplomatic and military power

- it acts as a buffer between Germany and France

- it’s more outward looking than the rest of the EU

- it’s a key intermediary with the US

But perhaps the key point is that post-Brexit, the EU would want to discourage others from leaving.

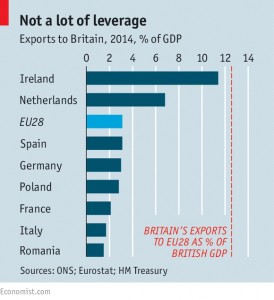

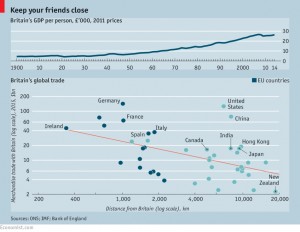

And the export argument is not compelling.

- Britain exports 12.6% of GDP to the EU, but imports only 3.1% of EU GDP.

The second article took the more reasonable position that the referendum result will have little long-term effect on the UK economy.

- Media forecasts of the 2030 impact range from negligible to -9.5%.

There are two reasons not to worry:

- the long-term trend of GDP growth is very steady, apart from during wars, and in the inter-war years (monetary policy was to blame here)

- neither joining the EU in 1973 nor leaving the ERM in 1992 had much effect

- Britain would remain a European country, and trade seems to follow proximity

- it’s possible however, that the terms of trade would deteriorate

So perhaps we should worry a little bit. We’ll know soon enough.

Until next time.