Weekly Roundup, 8th December 2015

We begin today’s weekly roundup in the FT, with the Chart That Tells A Story.

Contents

UK household spending

Adam Palin looked at UK household spending for 2013, split by disposable income quintile. It turns out that spending on some things is driven by income, but on others it is not.

The rich spend more than double what the poor do – 31% of spending is by the top fifth, while only 13% is by the bottom fifth.

- But housing, including heat, light, water and communications, is fairly flat – £53bn (38%) for the poorest, £61bn (19%) for the richest.

- Low earners renting privately around London often spend more than 50% of disposable income on housing costs.

- Food (including alcohol and cigarettes, but excluding restaurants) is also “income inelastic”. The poor spending 15% of discretionary income here, the rich 11%.

- Education spending appears to be concentrated amongst the poor, but that is an artefact of students living together in shared houses of low earners.

Which leaves recreation (including restaurants and hotels), “miscellaneous” and travel – the “elastic” parts of spending.

- Forty percent of the £206 bn spent on recreation came from the richest fifth, with only 9% from the poorest fifth.

- Miscellaneous includes health and education, plus things like insurance.

- The rich spent four times as much as the poor on travel (including running a private vehicle).

So not too many shocks there.

Lord Lee

Claer Barrett chatted to Lord Lee, the UK’s first (public) “ISA millionaire“.

I’m sure many readers are familiar with Lord Lee’s story – he features in Free Capital, the book by Guy Thomas about a dozen successful UK investors, and writes an increasingly irregular column in the FT – but here’s a quick recap anyway.

[amazon template=thumbnail&asin=1906659745]

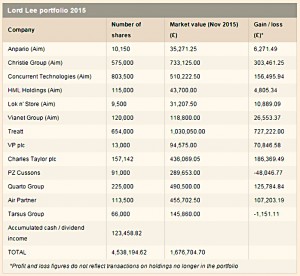

Lord Lee has turned £150K into £4.5M since 1987. He uses a buy and hold strategy, with a focus on smaller, family controlled companies.

- He looks for companies where significant profit growth could drive a PE re-rating, and often a takeover from a larger firm.

- He generally likes to run his profits, but he is not averse to “top slicing” – taking partial profits and reinvesting the proceeds.

- He’s a big believer in the ISA tax wrapper. He reinvests all dividends, and pays management fees with money from outside the ISA.

- He thinks that the key to success is to avoid losses.

- He’s also keen on shareholder participation and regularly attends AGMs.

- He likes “UK regulated and quoted companies that give the advantage of UK corporate governance, but trade internationally”.

- Originally he targeted “Double 7s” – companies with a dividend yield of 7% and a PE of 7. These companies don’t really exist today, and if they do they are probably value traps.

- He avoids biotechs, exploration stocks and startups, and knows nothing about the internet.

- He won’t invest in companies that don’t pay a dividend, and often sells if the dividend is cut.

- He’s not a fan of the new crowdfunding platforms.

This is his 2015 portfolio:

He also provided his 12 golden rules:

- Try to buy shares on modest valuations – high yield, PE < 10 and/or – discount to net asset value.

- Ignore the overall level of the stock market and macro stuff – focus on your investments.

- Aim to hold for a minimum of five years.

- Buy businesses that you understand.

- Ignore minor share price movements.

- Buy established companies with profits and dividends.

- Look for optimistic director-speak.

- Focus on cash-rich companies with low debt.

- Look for directors with meaningful shareholdings and good reputations.

- Look for a stable board, and few professional adviser changes.

- Use a 20% stop-loss, but don’t enforce during a large market fall.

- Let profits run.

Lord Lee’s achievement is significant however you look at it.

I think that 1987 was a good time to start investing in small companies, and that it would be hard to do as well starting in 2015.

But you needed to hold your nerve through perhaps four significant market crashes to build up that size of portfolio. I would also find it impossible to hold £4.5M in 13 UK stocks, so hats off.

Lord Lee’s rules also stand up to examination. Whether sticking to them would produce a rich crop of firms to invest in now is another thing.

Decumulation

Don Ezra took a look at decumulation – taking money out of your pension after you retire. Don thinks there are three options to address three fundamental goals.

- Longevity – we don’t want to outlive our savings.

- Safety – with no income we can’t top up the pot if it goes down

- Growth – we’d like our lifestyles to slowly improve if possible

The three approaches are annuity, minimum drawdown and self-insurance.

We’ve said many times before that annuities are a bad purchase at the moment.

- They are expensive – especially with inflation-protection, and at ages less than 75 – and you have to live for many years to even get your initial investment back.

- You can’t get your money back if you change your mind.

- But they do provide a guaranteed income for the rest of your life.

Minimum drawdown is popular in the US. You work out your life expectancy and divide the number of years you have left into your pension pot. That tells you how much to withdraw that year.

- The rest of the pot stays invested in whatever assets you fancy.

- Next year you update your pot size and life expectancy, and go again.

- This way you can never quite run out of money, though your income can decline as you get older.

- But you will be starting from a higher income than an annuity.

Self-insurance is bolder. You pick a target age that you want to have income until (normally more than 90, which is becoming increasingly common). Then you take out as much per year as that target allows you.

- This will produce even higher initial income than minimum drawdown.

- But if you live to your target age you will run out of money.

Don recommends two variations to cope with the disadvantages of each approach.

The first is half and half – 50% of your pot is used for minimum drawdown, and 50% on a distant target age (say 110).

- This gives you the chance of growth, with a more gentle reduction in income at advanced ages if the growth doesn’t materialise.

The second is the deferred annuity. This is Don’s personal approach.

- An annuity that kicks in at age 85 costs 10% to 15% of an annuity at 65.

- The rest of the pot uses the self-insurance approach, with target age 85.

I like Don’s idea, but deferred annuities only exist in the US at the moment.

- Over here you would have to keep part of you pot in reserve to buy the annuity when you no longer fancied managing your drawdown pot.

Here’s to deferred annuities turning up in the UK soon.

P2P investment trust

Emma Dunkley reported that P2P platform Funding Circle has launched its first investment trust. The Funding Circle SME Income fund listed last week after raising £150M from institutional investors.

It will provide loans to small businesses in the UK, US and Europe and target a dividend yield of about 7% pa. It is eligible for SIPPs and ISAs. There are platform fees but no management charge or performance fee.

Window Tax

Tim Harford revisited the window tax, as a good example of a bad tax.

Basically, the more windows you had, the more tax you had to pay. This sounds fair at first sight:

- rich people have bigger houses with more windows, so they pay more tax

- windows are easy to count from outside, so the tax was easy to assess

- the number of windows doesn’t change, so the tax is hard to avoid

But there were problems in practice.

- One of the big ones was regionality – cheap houses in the country ha just as many windows as expensive ones in London.

- And the number of windows does change: when William Pitt tripled the tax in 1797, thousands of windows were bricked up.

- And since the landlords of the poor paid the tax, the poor were not permitted windows.

There were also problems with “notches”: there was no tax until the 10th window, at which point all 10 were taxed. There were further notches at 15 and 20 windows. ((This is the way stamp duty worked until last year, when a new system that straightforwardly punishes high-end transactions was introduced ))

The good thing about notches is they demonstrate changes in behaviour. Not surprisingly, many houses in the 1700s had 9, 14 or 19 windows.

And this behaviour – bricking up a window or two – benefits no-one. The homeowner has less light and fresh air, and the government doesn’t collect any tax. ((We saw last week that it’s impossible to persuade UK citizens to cough up more than 36% of GDP in tax ))

There are lessons here for good taxes too. Tim thinks it would be a good idea to bring in a carbon tax. People would change their behaviour to avoid the tax by reducing their emissions. Which is what we want.

The adage `free as air’ has become obsolete by … the imposition of the window tax. – Charles Dickens, 1850.

Dickens managed to get rid of the window tax – levied since 1696 – within a year. But the other lesson is that, as Tim puts it, “it’s perfectly possible for a bad tax to last for 155 years”.

Carbon tax

In the week of the Paris climate change summit, Tim’s analysis has given us a tenuous link to a carbon tax, which the Economist looked at.

The idea behind the tax – popular with economists (and the Economist) but not with politicians – is that producing carbon (eg. by burning petrol) has “externalities”.

- It imposes a cost on others (global warming) that is not built into the price of petrol (or coal etc.), and should be.

- This would discourage the use of carbon-intensive fuels.

Either you impose a tax, or you decide on an acceptable level of emissions, and introduce tradeable permits to pollute.

- Permits have worked in the US power generation industry to reduce sulphur dioxide.

- British Columbia has a high CO2 tax ($24 a tonne) that is reducing emissions by 5% to 15%.

- The EU system of permits hasn’t worked so well, since government chose high emissions ceilings to protect local industry. Permits here trade at $9 a tonne.

- Even worse, 80% of global emissions are untaxed.

- Politicians worry that taxing emissions kills jobs. US republicans call it a “tax on life”.

The problem is one of asymmetry – the costs of carbon fall on a few dirty energy producers, but the benefits accrue to the whole of mankind. It’s another angle on the tragedy of the commons.

The Economist has a few ideas to help a carbon tax be accepted

- realistic alternative energy sources, which first means publicly funded research

- buying-off the opponents of the tax with its proceeds

- this is inefficient – the proceeds should go to all, by reducing universal taxes – but it’s better than having no carbon tax

- carbon tariffs on imports from places which do not themselves tax carbon

I think the third proposal gets to the heart of the problem.

Whatever the Paris talks achieve on paper, in practice the emerging markets – particularly China and India – are unlikely to accept a lower standard of living than the West in order to avoid potential disaster in 50 or 100 years time.

The developed world developed through the use of fossil fuels, and there’s no moral argument to persuade the EMs not to do the same.

So it comes down to whether we can really afford not to buy their carbon-tainted products.

Climate change for investors

Buttonwood pointed out whatever happens, investors have to take climate change seriously.

- Fossil fuel producers and users will probably face higher taxes and regulatory burdens.

- Some reserves will probably be left “stranded” in the ground.

- Extreme weather will affect other industries.

Moody’s says that power generation and coal mining are already at risk.

- Carmakers, miners and oil refiners have “emerging, elevated” risk.

- Many more firms face risks in the medium term (> 5 yrs ahead).

- But that still leaves most corporate bonds in the low-risk bucket.

Some investors are beginning to boycott the dirtiest industries.

- Others are trying to engage with management to change their behaviour.

- Still others are weighting portfolios to companies that will do well out of carbon reduction (LED bulbs and renewable energy etc).

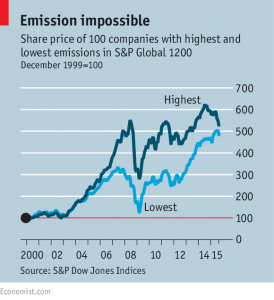

Standard & Poor’s looked at the 100 highest and lowest emitters in its global index of 1,200 stocks. The highest emitters have done marginally better since 1999.

- Of course, this period covers a commodity boom, and since the oil price crash, the low emitters have caught up.

- But low energy prices don’t suit renewables firms either.

Yuan joins the SDR

The newspaper also reported on the IMF’s decision to add the yuan to the Special Drawing Right (SDR) – a basket of currencies used as its unit of account – in 2016.

Not much is priced in SDRs, so the world need not rush to buy yuan-denominated assets. This in turn means the Chinese currency might not strengthen dramatically in the short-term.

Symbolically, admission to the SDR says that the yuan is a safe, liquid asset reserve currency.

Paradoxically, the implication that the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) now needs to manage the currency like the other SDR central banks (of the dollar, euro, pound and yen) means it may fall in value.

Use of the SDR may increase in the future. For example, some would like to value commodities in them to reduce volatility.

Unless China relaxes it’s de-facto peg to the dollar, this switch would now increase the effective dollar weighting, and volatility.

The downward pressure is indicated by the decline in China’s FX reserves, from nearly $4 trn to $3.5 trn, as the PBOC sells dollars to support the yuan.

The link to the rising dollar means that the yuan is near an all-time high in trade-weighted terms.

Poverty

The Economist also reported on the UK government’s plans to change the definition of child poverty.

They start with a reference to Adam Smith, who noted that although wealthy Greeks and Romans had no linen shirts, an 18th century European labourer would be considered disgracefully poor without one.

The passage is often used to defend the idea that poverty is relative.

Labour had previously committed the UK to reducing the rate of “relative child poverty” to 10% by 2020.

Relative poverty means an income below 60% of the median for a household of two adults (whether or not the household has two adults).

The median is £23.5K, so poverty begins below £14K – above the full-time minimum wage for a single parent. There are 2.3m children living in “poverty” this year – nearly one in six.

The problem with using a financial line is that the easy solution is to throw money at the problem.

The new Welfare Reform and Work Bill will replace income measures of child poverty with “life chances” – relative performance on education and employment, drug and alcohol dependence, family breakdown and debt.

Currently 63% of children living in “poverty” have at least one carer in work, up from 54% in 2010. Under the new proposals, these children won’t show up.

I grew up in poverty 50 years ago, and I can certainly testify to the changes since then. The richest children in my town lacked most of the luxuries enjoyed by the poorest children today.

Relative poverty is difficult to eliminate other than through socialist re-distribution, so I’m all for getting rid of this definition.

But at the same time, I’d rather we had an absolute measure than a social work fudge.

We need benefits and minimum wages systems that guarantee that beneficiaries aren’t in poverty, however we as a society choose to define it.

Zuckerberg’s charity

Finally, the newspaper described Zuckerberg’s announcement that he would give away 99% of his wealth to charity. His family’s shares in Facebook – worth around $45 bn – will be given to the portentously-named Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (CZI).

I’ll ignore the virtue signalling of the public nature of the pledge, and the soppy letter to a new-born child, and focus on the catches:

- Zuckerberg will retain control of the votes attached to the shares

- he’s only actually committed to transferring $1 bn of stock per year for the next three years

- CZI is a limited liability company rather than a charity – this means he can lobby the government and invest in profit-making companies

So really it’s just another company that Zuckerberg controls, to do all his non-Facebook, “change the world” stuff. Rich people do like to be popular, even if – especially if? – the things they did to get the money are not so popular.

I’d rather Zuckerberg had given the money quietly to someone more skilled in charity work, or even directly to people who need it. And I’d rather Facebook paid more than £4K per year in UK tax.

Until next time.