Weekly Roundup, 1st December 2015

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with the Chart That Tells A Story.

Contents

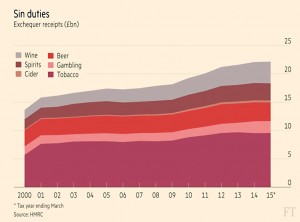

Sin duties

In the week of the Autumn Statement (AS), Adam Palin took a look at sin duties. He broke down the tax contributions from the nation’s drinkers, gamblers and smokers over the past 15 years.

Total taxes over the period were almost £300bn, excluding VAT. Last year’s figure was £22.1bn, up more than 60% from 1999-2000.

And this is despite the fact that people are smoking and drinking less. Smokers fell from 28% of the population in 1998 to 19% in 2013m and alcohol consumption in 2014 was 7% below 1999 levels.

The duties themselves have of course been going up.

- Tobacco is the biggest money spinner, with only Ireland within the EU having more expensive fags – a pack of 20 in the UK costs £7.98, including £6.17 of tax.

- Beer has got off lightly – duty is up 41% compared to 39% inflation – but spirits and in particular wine (which has grown in popularity) have been hit harder.

- Gambling duties have been relatively flat. Most money is raised from the lottery, but the growth in gambling machines (mostly in bookies shops) has also contributed.

Stealth tax and Buy-to-Let

Merryn’s column was also about the Autumn Statement. She began with stealth taxes. The AS contained five of them – a levy, a duty, a delay and two freezes:

- the apprenticeship levy is a 0.5% tax on company payrolls

- stamp duty was increased for second and BTL homes

- the delay to automatic pension enrolment will raise £840M (pensions tax relief that won’t be needed)

- the annual Isa allowance was frozen at £15,240 and

- the earnings threshold for student loans repayment has been frozen at £21K for five years

Between them, these five should raise £28bn over the next five years.

Merryn also discussed the impact of the stamp duty surcharge on buy-to-let (BTL).

I’m not a BTL investor, ((Technically I am, as my sister and I rent my late father’s terrace in Manchester to a housing association )) so I hadn’t looked at this in detail, but:

- duty on a £200K BTL house is currently £1.5K

- from next April it rises to 7.5K

The key point is that this extra £6K is cash upfront.

- Since BTL lenders usually require a 40% deposit, a £200K house needs £81.5K to cover the deposit plus the stamp.

- Next April, £81.5K becomes £74K after stamp duty, which can only serve as the deposit on a house worth £185K.

In theory, the 2.5 times gearing in BTL means that a 3% duty increase could depress prices by 7.5%.

Personally, this is a silver lining – perhaps I will be able to buy a cottage in Cornwall after all. Or perhaps holiday homes won’t be affected in this way – only time will tell.

No housebuilding boom

Neil Collins wasn’t convinced that the AS would lead to the planned housebuilding boom. Assuming that the Treasury can find the money, there are two other problems:

- a shortage of building skills

- the last recession saw a lot of small builders leave the industry, and one in eight of those remaining is over 60

- more than 1M more construction workers would be needed to build 300K homes a year – but presumably some of these could be imported?

- private sector housebuilders don’t want to build quickly

- their business model is designed to capture rising land values

- this in turn requires a chronic housing shortage

The Economist also had its doubts:

- low-income families might find saving a deposit (even for shared ownership homes) difficult, but all the new homes are to buy rather than rent

- the “starter home” price caps of £450K in London and £250K elsewhere may in practice become price floors

- the extended “Help to Buy” scheme in London – which offers a 40% interest free loan – will just push up prices

The one housing change they liked was a commitment to planning reform, but even here the devil is in the (so far unannounced) detail.

Reshaping the state

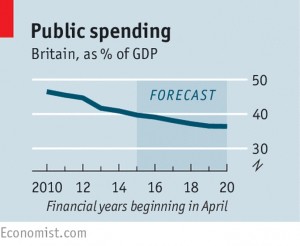

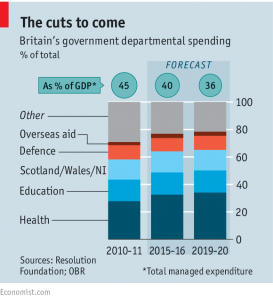

The Economist’s other three articles on the Autumn Statement (1, 2 and 3) were about shaping the British state. Although the U-turns in the AS (tax credits, police cuts) made the headlines, the reshaping is more important.

Inheriting a deficit of 11.1% of GDP in 2010, Osborne aims to reach 2020 with a surplus.

- Spending will fall from 45% of GDP in 2010 to 36% in 2020.

- Actual spending in inflation-adjusted cash will be only 1% lower than in 2010.

As an aside, at the Gold, Bears and Traders show on Saturday, I saw a presentation from Mark Littlewood, DG of the Institute of Economic Affairs.

Mark was in favour of Hong Kong-style low taxes and low government spending, to improve prosperity. One of his slides ((Actually taken from The Guardian, but I can’t find it on their site today )) showed the tax take against government spending for the last 50 years.

There were two striking points:

- no matter what the government or the tax policy the actual tax receipts averaged 36% of GDP, plus or minus 4%

- we’ve been spending more than that for pretty much all of the past 50 years

Mark suggested that 37% of GDP was the maximum size of state that we can support. So Osborne’s 10-year “austerity” programme is merely returning us to where we should have been all along.

The other major change to the state is the devolution of fiscal and spending power away from Westminster.

In practice the cuts will be tougher than they seem, mainly due to demographic pressures on schools and the NHS.

- An 85-year-old receives five times as much NHS spending as a 40-year-old, and double that of a 70-year-old

Government departments have been cut so far without much impact to services of public satisfaction. The next stage will be a lot more outsourcing.

- The Economist would like the surplus target to exclude capital spending on infrastructure.

- I can see the benefit of that in the short-term, (a boost to productivity) but the books have to balance eventually, and from Osborne’s perspective, just before the 2020 general election would be the perfect time.

- They would also like the ring-fences around health, eduction, defence and foreign aid to be removed, to avoid distortions like the justice department charging criminals to use the courts.

- I agree – including spending on “the Nations”, close to 80% of spending will be protected by 2020

- They are also opposed to the triple lock on the state pension.

- I am not, because the pension remains well below the minimum wage and the benefits cap.

Bagehot sketched Osborne as a liberal idealist and follower of John Locke:

- Locke believed that people tend to be decent, wise and fair

- Osborne is optimistic about human nature but wary of state bloat

He wants to reduce government’s role and move from the subsidy state to the enabling state.

Osborne the PM would try to forge “a benign environment for individuals, firms and municipalities” but be “less willing to meddle in how they proceed – or to catch them when they fall”.

I can live with that.

Currency strength and stocks

Back in the FT, Ken Fisher wanted to debunk a myth about the impact of currency strength on growth, imports and exports, and stock markets.

The general understanding is that a strong currency will hurt exports, company earnings and hence the stock market.

But Ken can’t find the evidence.

- for example, the yen’s plunge since 2012 hasn’t led to soaring exports and rapid growth for Japan.

In fact, he can’t seen any relationship between long-term exchange rates and international trade.

- exports and imports generally rise and fall together, driven by economic growth

- supply and demand in end markets determine how expensive British goods are overseas

- for exporters, the hit to revenues is usually offset by cost savings

- since most either import components and raw materials or have factories abroad

- all have foreign shipping costs

The big driver of the recent falls in UK (and US) earnings is the collapse in commodity prices. Non-commodity firms are doing well.

Ken expects positive surprises to push stocks higher over the next over the next 12 to 18 months.

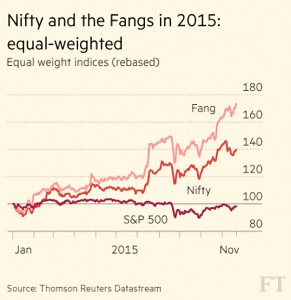

Nifty and the FANGs

John Authers looked at how a handful of large stocks dominate the US bull market. The US bull is into its seventh year, but it is growing much narrower.

Initially it was dominated by small companies, but now a handful of stocks are driving the market.

In a worrying development, these stocks are starting to attract nicknames and acronyms:

- the FANG stocks are Facebook, Amazon, Netflix and Google

- the Nifty Nine are those four plus Priceline, Ebay, Starbucks, Microsoft and Salesforce

- note that Apple is not on either list

Each of these groups is up 60% in 2015, while the S&P 500 is up about 1%. The equal-weighted S&P 500 is down in 2015 – most stocks are down.

Underpinning this shift is a move to services rather than manufacturing in the US economy, but these stocks are expensive:

- the Nifty Nine has a collective PE of 45, double that of the S&P 500

- they also look expensive compared with their sales

There are echoes here of the “Nifty Fifty” of the early 1970s, or the dot-com boom.

John points out that this makes things hard for US fund managers. The only way to beat the market is to over-weight a few large stocks that already look overvalued – this is a hard strategy to justify.

Here in the UK, large stocks have under-performed, due to the large weighting to energy and resources companies. To outperform, just avoid these sectors and over-weight smaller companies.

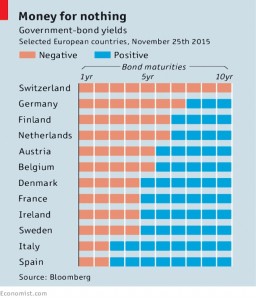

Negative interest rates

The Economist revisited negative interest rates. The ECB’s deposit rate – which it pays to banks on their reserves – went negative in June 2014, and hit -0.2% three months later.

- The December 3rd meeting of its rate-setting board is expected to cut again (and announce more QE).

Until recently, zero was thought to be the lowest possible interest rate. Below that, the rational choice is to hold cash (under the mattress if necessary). But central banks appear committed to testing the lower bound.

For most of the active players (other than the ECB – Denmark, Switzerland and Sweden), the goal is to suppress their currency against the euro. So they need interest rates even lower than the ECB.

- the deposit rate in Denmark and in Switzerland is now -0.75%

- in Sweden it is -1.1%

Commercial banks have not moved to cash because this would be costly:

- they would have to move (and insure) lorries full of banknotes amongst themselves each day

- banks have also passed on some of the cost of negative rates to their corporate clients, whose alternative (buying safe and liquid bonds) also shows a negative yield

Retail customers have been shielded to date, which dents banking profits.

There have also been calls to abolish cash, which would make it harder for retail investors to escape negative rates, and might also shrink the black economy.

- But there would still be flight to foreign currencies and / or precious metals

- Advance payments to tax authorities would also need to be outlawed

- Banker’s drafts could be used as a cash substitute, and perhaps even as a currency

- Gift vouchers and pre-paid cards and passes could have the same impact on a smaller scale.

Eventually, companies would make payments quickly and try to receive them slowly. They would grow their inventories.

We haven’t got there yet, but it remains the direction of travel.

Lehman’s and HBOS collapses

Buttonwood looked at the failures of Lehman’s and HBOS in 2008 – there’s a new book out on the former and a recent report on the latter.

[amazon template=thumbnail&asin=1784993409]

Alan Greenspan, the former Fed chairman famously admitted that he didn’t understand why bankers would take risks that would destroy their own businesses.

- The first step for both banks was to move outside their area of core competence:

- HBOS was a mortgage lender and to compete with HSBC and Barclays, took on riskier borrowers

- Lehman was known for bond-trading, but moved into property lending

- By taking on more risk as competitors retreated, both grew market share, aiming for long-term success.

- Risk control systems then failed.

- Lehman’s risk department had almost 400 staff, but was over-ruled.

- HBOS’s stress tests used a hypothetical mild downturn.

- Both became heavily dependent on short-term wholesale funding, and hence reliant on investor confidence.

- This is probably why distressed assets were not written down quickly.

- Both boards lacked recent experience of banking.

- Lehman also controlled more than 7,000 legal entities – of which 209 were subsidiaries – and had assets of $700 billion.

- Not easy to control.

- And finally, a long period of benign economic conditions led to over-confidence.

- Their bosses believed that if they didn’t keep growing, they would be replaced.

Disruption

And finally, Schumpter took a look at whether disruption has itself been disrupted.

Clay Christensen of Harvard Business School came up with the concept 20 years ago.

- He is now is regularly named as the world’s most influential management guru.

- The Economist is worried that by sticking to his version of disruption, other forms will be missed.

Christensen’s theory is that well-run incumbents can fail by ignoring upstarts that are changing the rules:

- first they use “unproven or inferior technologies and business models” to offer a cheap alternative to established firms

- this wins the customers that established firms regard as unprofitable

- as the incomers get better, they take more share, until they are ready to attack the core customers

So Christensen believes that disruptors are newcomers, and attack the low end first.

- He doesn’t believe that Uber is “genuinely disruptive” because it didn’t begin by offering an inferior service to established firms

- but it is clearly disrupting the taxi business

- And well-established Apple is probably the most successful disruptor of the last decade

- Apple disrupts by inventing new categories of product above the existing ones.

- Netflix also attacked Blockbuster’s core customers – film fans prepared to pay a monthly fee for unlimited access

- Netflix and Uber grew by dealing with “pain points” as much as by offering a cheaper product

- The biggest threats today are already well-known:

- Google threatens carmakers, Facebook attacks newspapers and Apple is after TV stations.

Until next time.