Irregular Roundup, 4th July 2023

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup with mortgages.

UK Mortgages

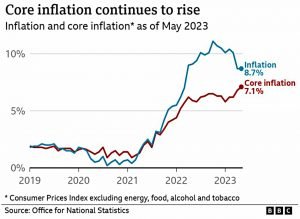

After the worrying inflation numbers last month, the BoE went for a 13th consecutive rise in interest rates since December 2021, opting (perhaps in a bid to restore lost credibility) for a 0.5% rate hike rather than the expected 0.25%.

The monetary policy committee (MPC) noted:

There has been significant upside news in recent data that indicates more persistence in the inflation process.

Jeremy Hunt said the UK had no alternative but to raise rates:

Our resolve to do this is watertight because it is the only long-term way to relieve pressure on families with mortgages. If we don’t act now, it will be worse later.

The latest rise has pushed up mortgage rates to levels that many people can’t recall, leading to a lot of political debate on what the government might do to fix the “mortgage crisis” (which comes hot on the heels of the “cost of living crisis”).

Liberal leader Ed Davey asked for “emergency support” to prevent homeowners (and indeed, renters) from losing their homes.

- He wants a Mortgage Protection Fund, paid for by reversing “tax cuts” to banks.

- Those whose mortgage payments went up by more than 10% of their income would receive up to £300 a month.

There are much more sensible options available than free money (which we’ll come to later).

- Free money (in the form of furlough payments during Covid) is how we got into this mess (the painfully slow reaction from the BoE didn’t help, either).

For once, Labour was more sensible, asking that borrowers should be able to temporarily switch to interest-only plans (a privilege usually reserved for those with the best credit) and that mortgage terms should be extended where necessary.

- They also wanted a six-month grace period before repossession and an amnesty from asking for help impacting credit scores.

Shadow Chancellor Rachel Reeves agreed that direct financial support could fuel price rises.

Actual Chancellor Jeremy Hunt has ruled out a tax break for mortgage holders:

Those kind of schemes, which involve injecting large amounts of cash into the economy, would be inflationary.

Hunt met with bank bosses to agree on a scheme that goes even further than Labour wanted:

- Borrowers can switch to interest-only, without impacting credit scores.

- They can also extend their term, with a six-month option to return to their original conditions.

- And the repossession grace period will actually be 12 months.

Hunt said:

There are two groups of people that we are particularly worried about. The first are people who are at real risk of losing their homes because they fall behind in their mortgage payments.

The second are people who are having to change their mortgage because their fixed rate comes to an end, and they’re worried about the impact on their family finances of higher mortgage rates.

Of course, the costs of all this help will have to be recouped from other sectors of the lending market, so these measures are not a silver bullet.

There are a few issues here.

- Morally, borrowers should have expected rates at this level at some point during the life of their mortgages.

- These are not historically high rates, and there is no precedent for the government bailing out homeowners.

- It’s true that many commentators said that inflation would be transitory, with the implication that interest rates wouldn’t get this high, but borrowers need to carry out their own stress tests.

- It’s also worth noting that high house prices (and lax lending rules) mean that loan values are higher than they used to be, and therefore the monetary impact of rate hikes is larger than before.

- Practically, the “high” interest rates are a means to an end – we want to get inflation down to somewhere closer to the old 2% pa target (I think we might end up closer to 4%, but that’s an argument for another day).

- This won’t happen without many sections of society feeling the squeeze – high wage settlements and lots of disposable income won’t bring down inflation

- Commodity inflation (energy and food) is usually self-correcting (a shortage soon leads to a glut) but services inflation can easily turn into a wage-price spiral (we’ll look at how much that matters below).

- Again practically, the UK mortgage market has a longer duration than it had when I was a borrower (there are also fewer people with a mortgage and more who own their home outright).

- We might not have the 15- and 30-year fixes that are popular in the US, but we do have a lot more 2-, 3- and 5-year fixes than we used to.

- This means that the effects of interest rate hikes (both bad – for homeowners – and good – for the fight against inflation) are now staggered rather than instantaneous.

There has been some discussion around why the UK doesn’t have long-term fixes, and though I share the regret, I’m not convinced that borrowers would choose higher long-term rates over shorter, lower fixes.

- Mortgage brokers also have an incentive to churn two-year fixes.

Whatever the reason, the new market structure means that there will be less pain than there might have been, and the effectiveness of the rate hikes will be lower than it might have been (and possibly now even lower because of these new relief measures).

- Looked at another way, the impact will continue for longer, and so continued rate hikes risk being pro-cyclical as we head into 2024 and beyond.

So most options are on the table: higher rates, a pause, and a recession (which would mean rate cuts).

- Factor in the election in 18 months’ time, and UK interest rates are more interesting (forgive the pun) than they usually are.

Wage-price spirals

The Economist said that wage-price spirals are a poor predictor of future inflation.

The historical parallel often trotted out in discussing wage-price spirals is the 1970s. Price and wage inflation seemed to interact throughout that decade, much as the spiral framework suggests.

By this, they mean that a surge in price inflation was followed by a surge in wage inflation, which in turn was followed by more price inflation. But:

The repeated waves of inflation stemmed more from successive oil-price shocks (in 1973 and 1978) and trade unions’ practice back then of pegging salaries to the cost of living, guaranteeing a ratchet effect.

It was a contractual rather than an economic mechanism.

A recent IMF study looked at 79 wage-price spirals in advanced economies, dating back to the 1960s.

The “great majority” (they omitted the exact percentage) of short-term spirals were not followed by a sustained acceleration in wages and prices.

The Chicago Fed looked at “non-housing services” in the current inflationary episode:

Mr Barlevy and Ms Hu concluded that wages do help to explain this segment of inflation: nominal wage gains have outstripped productivity growth by a sizeable margin over the past year. Facing that cost squeeze, service providers would naturally want to raise prices.

But the link is the wrong way around:

Inflation helps to forecast changes in labour costs, but changes in labour costs fail to predict inflation. Service providers, in other words, raised prices before rising wage costs hit their bottom line.

So wages are a lagging indicator, at least in the short term.

Wages and prices can be driven up by the same force: excessive spending in the economy compounded by shortages of both products and the workers to produce them.

It’s overheated economies, in general, we need to worry about, not wages in particular. This doesn’t mean that spirals never happen:

Were inflation to stay very high for a long time, peoplemight start to view fast-rising prices as a basic fact of life and incorporate that assumption into their wage demands.

This is exactly what we’re worried about right now in the UK.

- The problem is that reducing the demand for workers – without triggering a recession – is tricky.

Forecasting

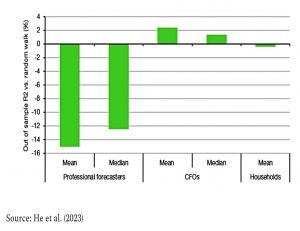

Joachim Klement looked at forecasting, using three US surveys:

- The Livingstone Survey of professional forecasters conducted every six months by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia.

- The CFO survey by John Graham and Campbell Harvey.

- The compilation of different household surveys by Stefan Nagel and Zhengyang Xu.

The surveys each target a group at a different level of financial sophistication, and their results do not agree.

The long-term average market return is 8.9%, yet the average forecast return is less than half thatat 3.8%! The average return of the CFO survey is 4.0% and the average return from thehousehold surveys is 6.7%.

When compared with a random walk (which assumes that next year’s return will be the same as the previous year) then the CFOs are marginally better than guessing, and the forecasters and households are worse.

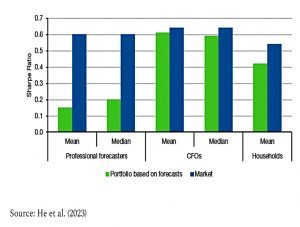

The next step was to form portfolios based on the forecasts.

No matter which forecasts they used, the so-called [mean-variance] optimised portfolios were worse than the market portfolio and effectively destroyed returns. There simply is no wisdom of crowds when it comes to forecasting financial markets.

Which has implications for portfolio construction:

Investors should use robust optimisation methods that either don’t use any explicit return forecasts or are designed to incorporate forecasting errors. The simplest way is to go for equal-weight portfolios.

Minimum variance portfolios and resampled efficient frontiers will also work, but what won’t work is the normal practice of using optimisation based on forecast returns for different asset classes.

Quick Links

I have four for you this week, the first three from The Economist on AI.

- The Economist explained How corporate America is deploying AI

- But warned that The widespread adoption of AI by companies will take a while

- And that The bigger-is-better approach to AI is running out of road.

- Alpha Architect was Diving Into the Performance of Factors.

Until next time.