Weekly Roundup, 27th March 2018

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with Merryn’s column. This week she was writing about trust.

Trust is rare

Merryn puts the rise of cryptocurrencies down to a lack of trust in fiat money, caused by the vast money printing (QE) as a response to the 2008 crisis.

- Until then, only gold-bugs felt that way.

Apparently at a recent conference she was part of a panel which discussed which crypto you could trust.

- The answer was Monero (although something more like Amazon Coin is likely to win out in the long run).

At another conference, her round-table looked at safe storage of personal data, and biometric data in particular.

- She worries that biometric data could be translated into emotional reactions (basically the thought police) under a totalitarian regime.

She eventually brings the topic back closer to home by wondering if there are asset managers you can trust for the long term.

She chose:

- Baillie Gifford (( Where I think Merryn’s husband works, and she may be a non-exec on one of the trusts ))

- Fundmsith

- Lindsell Train

- Troy, and

- Legal & General.

Choosing an adviser

Sticking with trust, Lucy Warwick-Ching looked at how to choose a financial advisor.

Regular readers will know that I don’t believe in advisors for most people, for three reasons:

- The vast majority of personal finance and investment activities are simple, and easier to learn than how to drive a car.

- IFAs add to your investing expenses, and low costs are one of the few areas over which an investor has direct control

- Since IFAs make money from you and your actions, there is an inevitable conflict of interests.

- At the very least, the relationship is an example of the agency problem.

Some people will have complicated situations, poor psychological reactions to adverse situations and / or will be very short of time, and for these people an IFA may be useful.

- Even for these people, coaching may be a better solution.

There’s more on why an adviser might not help here and here.

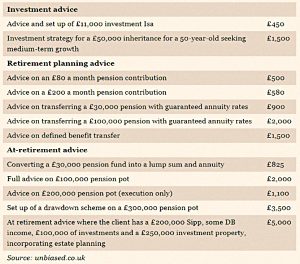

Lucy’s article included a handy table of IFA fees, taken from Unbiased, a site that lets you search for a local adviser.

Lucy’s eight steps were:

- Do you need an adviser?

- Which type of service do you want?

- Independent or restricted advice?

- Choose which level of advice you need.

- Finding an adviser.

- Choosing the right person for you.

- Keep your finger on the pulse.

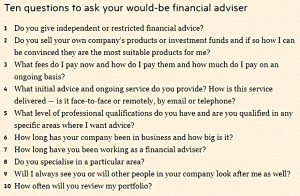

Lucy also had a handy list of ten questions to ask a would-be adviser.

Trade wars

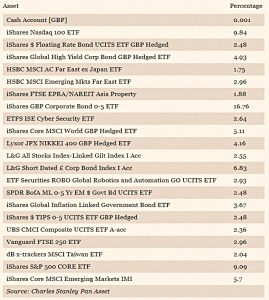

John Redwood has one of his regular updates on the ETF portfolio he runs for the FT.

- He was worried that Trump’s tariffs on steel and aluminium could lead to trade wars.

As a result, he has removed direct holdings in China from the portfolio.

- He already had no holdings in Europe (he sees Germany as another potential big loser).

He’s added to his short-term bond holdings, to protect against uncertainty.

CAPE

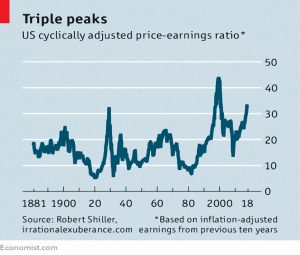

Over in the Economist, Buttonwood looked at a defence of the CAPE from Research Affiliates (RA).

- The cyclically adjusted PE ratio for the US market has only been higher in 1929 and 2000.

But although the CAPE has good long-term predictive power for future returns, it doesn’t work well in the short run.

- Peaks in the CAPE might match up to stock market peaks, but how do you know you are at a peak when it happens?

There are technical arguments against the CAPE, too:

- Accounting standards have changed and modern tech firms have more market power, making profits permanently higher (and increasing the present value of these future earnings).

- The ten-year look back means low earnings from 2008 are still included.

- Demographics (boomers preparing for retirement by buying equities) and low interest rates (discounting again) mean that valuations should be high.

RA don’t buy much of this.

- Profits tend to revert to the mean.

- Specifically, high profits means low wages, a populist backlash and more regulation and / or trade wars.

- Boomers are starting to retire, and will run down their equity pots.

- The ageing population will slow the growth in the workforce, and could lead to lower profits.

- Low interest rates reflect low growth expectations, which will not be good for stocks.

- Other markets have similar conditions, but lower CAPES.

- The US CAPE is 33, but Germany is on 20 and the UK on 14.

I think I’ll stick with my view that CAPE works pretty well over 10 years, but not so well over 10 months.

Mulligans

Buttonwood also looked at the investment version of mulligans.

In golf, people sometimes let a player retake a shot.

- And the same thing happens with fund managers.

We know that on average, funds won’t beat markets, since costs need to be deducted.

- The winning proportion over 10 years varies by market, from 2% to 15%.

Buttonwood was intrigued that the average 10-year fund return in the UK market was 7.3%, higher than the index return of 6.5%.

- The answer of course is survivorship bias.

Only funds that lasted the 10 years will be measured, and those that under perform will be closed or merged.

- Just 43% of the funds operating at the start of 2008 were still in business at the end of 2017.

A second problem relates to assets under management.

- A small fund which outperforms will attract new funds and grow.

As a larger fund, it will typically find outperformance more difficult.

- So a gap will open up between the fund’s track record (average return per year) and the average investor’s return (the average experience of any £1,000 invested in the fund).

Morningstar found this gap (in the 10 years to end-2013) to average 2.5% pa.

So be careful when you look at the stats from a fund.

Normal

The Economist also looked at what central banks think is normal.

- Their goal should be to control inflation and support growth, not to return to “normality”.

The BIS recently encouraged central banks to keep raising interest rates, despite market jitters.

- But perhaps that will put the global recovery at risk.

The central banks want to do three things:

But what is normal?

- Interest rates were more than 10% in the 1970s and 1980s.

- Over the last 20 years they have averaged 2%.

The Fed is targeting 3.5% by 2020, whereas the Bank of England’s target is just 1% by 2021.

- Neither would prevent more QE in the next downturn.

Japan, meanwhile, has had low rates for more than 25 years.

- Perhaps the new normal is low growth, low inflation, excess capital, stagnant productivity and ageing populations.

Or perhaps central banks should raise their inflation targets to give themselves some room to manoeuvre.

Pensions

There were a few interesting snippets about pensions this week.

The Pensions Policy Institute (PPI) reported that scrapping the triple lock on the State Pension would mean that more than 700K extra pensioners would be living in poverty by 2050.

- The Tories had planned to scrap the 2.5% pa lower limit from 2020, but abandoned this policy as part of their post-election deal with the DUP.

The number living in poverty (I’m going to guess this is relative rather than absolute poverty) would increase from 2.8M – if the triple lock remains in place – to 3.5M.

- The worst affected would be women and the low-paid “young”.

To be 68 by 2050, the “young” would need to be around 36 at present, but I think what they mean is that shrinking the state pension means the young (like everyone else) will need more private savings.

I think the triple lock is overkill, but I’m also aware that the UK has the lowest state pension of any rich country – it averages less than half of the minimum wage.

- So anything that leads to it increasing in value is good news.

BT announced that it is closing its final salary pension scheme.

Existing DB entitlements will be preserved, but future DB entitlements will be based on career average earnings, capped at £17.5K pa (but with the cap indexed to CPI).

- Entitlements on the rest of earnings would go into a DC pot.

- There are also some pay rises and increased contribution levels to sweeten the deal.

Although most private sector DB schemes have already closed, this approach might be a way forward in the public sector.

And a former head of the Pension Protection Fund (PPF) has launched a DB “superfund”.

- Alan Rubenstein’s fund will accept bulk transfers from DB schemes plans and consolidate them into a single occupational pension scheme.

His partners in the scheme are City financier Edi Truell (Disruptive Capital) and PE firm Warburg Pincus.

- The scheme – called The Pension Superfund – has launched with £500M of capital, but expects to grow to £20 bn over time.

The government revealed plans to promote DB plan consolidation in its recent DB white paper.

- Two thirds of the 5,600 existing schemes are currently in deficit.

Twitter pics

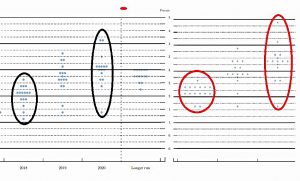

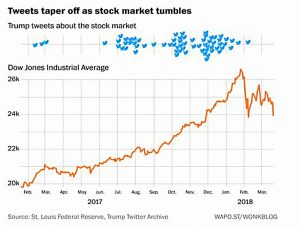

I have just two charts for you this week.

The first shows the increasing hawkishness of the Fed’s dot-plot from December 2017 (black ellipses) to this month (red ellipses).

The second shows how the volume of stock market tweets tails off as the Dow Jones index starts to slide.

Until next time.