Coronavirus Thoughts

Today’s post offers up a few thoughts on the pandemic, now that we are five months into it.

Contents

Previously

Since March, I’ve written five articles on how I have adjusted my investments in response to the coronavirus, and in April I wrote a post about the numbers side of the pandemic.

- Today I’d like to revisit the questions I tried to answer in April, and add a few new ones.

As before, I have delayed this article for a long time ink the hope that the situation would become clearer.

- But it seems to me that we are little further on than April, and if anything, the situation has become even more politicised.

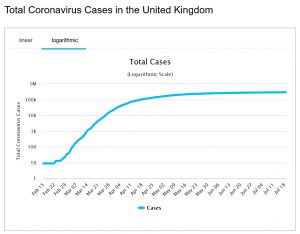

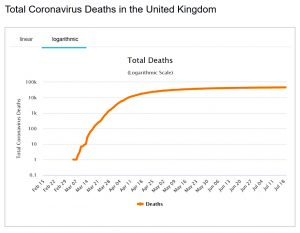

At the time of writing this article, there are 14.7M recorded cases and 611K deaths worldwide.

- Here in the UK there are 295K cases and 45K deaths.

The old questions

Here are the questions I asked back in April:

- How contagious is the virus?

- How deadly is the virus?

- How many excess deaths should we expect?

- How prevalent is the virus, particularly here in the UK?

- When will we have an adequate testing regime?

- What is the likely path of the pandemic in the UK?

- When might we have a vaccine?

- What are the exit strategies from lockdown?

- Can we trade lives against economic loss?

Many of these issues are closely related, with definitive answers to one issue requiring greater clarity on another.

- Before we start, here’s the usual disclaimer that I’m not a doctor, or an epidemiologist – I’m just someone who likes to analyse data.

Contagion

The ramping up of testing means that we have a much better handle on what the infection rate (the R number) is at any one time in a particular location.

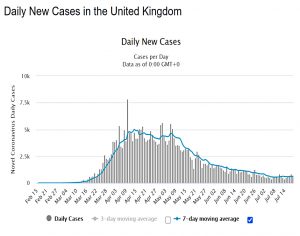

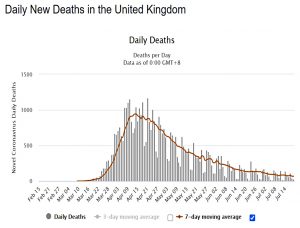

- It’s also clear that lockdown has a big impact on the R number (it flattens the curve).

But how infectious the virus is in the wild (without lockdown) is not clear.

- The rapid flare-ups of “second waves” in places which seemed to have the virus under control indicate that it’s pretty infectious.

As do the quick-fire changes in case rates in areas threatened with (or issued with) local lockdown orders (Leicester, Blackburn).

Several of the complicating factors from March remain:

- Some of those infected show no symptoms and will likely not present to the health system

- They will still be infectious, however.

- Around 80% of those who do show symptoms have a mild form of the disease.

- These people might stay home, too

- The symptoms associated with the disease are quite varied, complicating diagnosis.

- Most are also common to lots of respiratory diseases (colds, hayfever).

What we do know is:

- Social distancing, whether it be 2m or 1M+, seems quite effective (at great economic cost).

- Inside is much worse than outside, and singing/shouting/hugging is worse than chatting quietly.

- Handwashing is key, and masks help you not to infect others in closed situations.

- Two weeks of isolation seems to be long enough to wait out the incubation period for most people.

- The virus is quite hard to catch – there are lots of cases from cloistering (eg religious groups) and in situations where people might have repeated exposure (or exposure to a high viral load).

- This is particularly the case in the healthcare system, but also applied to transport (eg. buses and taxis) and also in shops.

John Authors quotes Andrew Brigden, chief economist of London’s Fathom Financial Consulting

on five possible explanations for the patterns we are seeing in R (no increase as mobility gets back towards normal):

- Fear provokes changes in behaviour, such as more frequent hand washing and the wearing of face masks, that prevent the spread of the disease but are not captured by

measures of mobility. - Heterogeneity across the population means that we all have a different ‘R’ number, with some people, including those with a large network of contacts, more likely both to acquire the disease and to pass it on.

- Once those people have been exposed, and are no longer susceptible, the average R will fall.

- The virus has spread far more rapidly than antibody testing suggests, which means the virus is running out of people to infect.

- Potential ‘super spreader’ events — such as nightclubs, and music concerts that involve a lot of people being close together indoors — are no longer happening.

- It is a seasonal phenomenon in the northern hemisphere, and it will return later this year in a ‘second wave.

I think 1 is likely, 2 is plausible and 3 is unlikely.

- 4 is partially true (in that such events are far less frequent) – note that this has serious sectoral economic consequences.

Unfortunately, 5 remains a serious possibility.

Deadliness

This ought to be the easiest question to answer since deaths are well recorded.

But:

- Some countries count dying with Covid as well as dying from Covid.

- Some countries record only hospital deaths and not those at home or in nursing homes.

- Deaths are (at least initially) often logged against the day of reporting rather than the day of death, adding noise to the data.

- Death rates vary significantly by age (in particular), gender and pre-existing health conditions (sick old men do worst) – and possibly by other demographic variables.

Around 6% of resolved cases have so far resulted in death.

- But countries have different methods of defining resolution and tracking recovery.

And many early cases may have been missed.

- Only 1% of open cases are in the “serious” condition (implying a forward death rate of less than 1%).

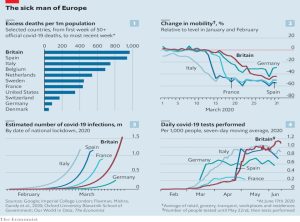

The UK is currently fourth in the deaths per capita table (behind San Marino, Belgium and Andorra).

- But this could reflect testing levels (the UK has carried out more than 13M tests) and the tragedy in the UK’s care homes, where many of the most vulnerable have already died.

The need to record deaths as being specifically from Covid-19 (whereas a similar death in 2019 might not have been attributed to flu) will also make things appear worse.

Excess deaths

We won’t really know how deadly the virus is until the pandemic is over.

- Around 600K people die each year in the UK, and the true impact is any excess deaths over this figure.

And even that is only a net impact.

Some of the trade-offs include:

- People (usually old and sick) who would have died anyway, many of them from a regular winter flu.

- People who won’t die from other contagious diseases that they won’t catch because of the lockdown.

- Varying accident rates in the home (up), the workplace (down) and the roads (down).

There are also second-order effects like increases in poverty, substance abuse, domestic violence and mental health issues – each of which would impact society’s goal of long and healthy lives.

- And people with “normal” diseases may not seek help, or may no longer be offered it.

The UK certainly appeared to have excess deaths in April and May, but they have fallen back to normal (and in some locations, to below normal).

Prevalence

Initially, the numbers of deaths are thus consistent with more than one scenario:

- Rare and deadly

- Common and not lethal to many

Most widespread testing studies have found no evidence for widespread infection, but this is complicated by the possibilities that (i) the antibodies don’t last long after fighting the infection and (ii) some young people in particular fight off the virus using T-cells, without ever producing antibodies.

Testing

Anyone can get a test now (at a price).

There are two types of test:

- Antigens – answers whether you have the virus today

- Some countries are using facial temperatures (measured using something like an infra-red camera) to do instant tests

- Antibodies – answers whether you have already had Covid (and might therefore now be immune)

My understanding is that the first test is now widely available.

- I haven’t had either test as yet.

Herd immunity

This idea seems to be off the table for now, as the virus doesn’t seem to have penetrated any community to the necessary levels.

- Of course, deploying a successful vaccine would be a form of herd immunity.

At the same time, a recent study by Guys and St Thomas’ suggests that for most people, the immune response only lasts a couple of months, which might make herd immunity impossible.

- Alternatively, regular booster shots of a vaccine might be needed.

Or antibodies could be a red herring, and lots of people might be able to fight off the disease using only T cells.

Vaccine

The unprecedented human effort towards creating a vaccine continues.

- Just this week the Oxford team reported goo early-stage results

The bad news is that we don’t have a good track record in creating vaccines in double-quick time.

- There’s still no vaccine for AIDS after 30 years, nor one for Hepatitis-C.

I remain sceptical that we can make billions of doses of a foolproof vaccine available within a small number of years.

- I am much more optimistic about the chances of successful treatments, or “semi-vaccines” which reduce the seriousness of the infection or improve our chances of fighting it.

We also have the hope that the virus mutates to a less deadly form, which often happens.

Lockdown exits

The UK full lockdown lasted 15 weeks, but conditions are far from normal here in London:

- Most people are working from home.

- Public transport capacity is below 20%.

- There is table service in pubs, but no bars or nightclubs are open.

- Sporting events and concerts are taking place behind closed doors or not at all.

We seem to be using a combination of testing and tracing – plus local lockdowns where necessary – to guard against new outbreaks.

Economic trade-offs

The cost of the lockdown has been unbelievably high – £190 bn in spending by the UK government.

- The furlough arrangements will continue until October, so it’s difficult to see much lasting economic damage as yet.

New questions

Did the lockdown work?

This is a difficult question to answer because we don’t have counterfactuals.

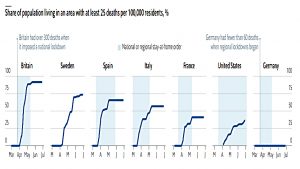

- Sweden is the poster-child for “no lockdown” and so far has more cases per million than the UK, but fewer deaths.

But finding truly comparable countries is difficult since population densities, demographics and cultural factors seem to play such a large role in how the virus plays out.

- Sweden seems to have done a lot worse than its immediate Scandanavian neighbours which used tighter lockdowns.

In the narrow senses of avoiding the flooding of the healthcare system, and getting the R number below one, lockdown clearly worked.

- But this has been a great economic and life satisfaction cost, and we don’t know whether these things might have been achieved without lockdown (for example, with just more hand-washing, masks and some social distancing).

How has the UK government performed?

This has become a deeply politicised issue, but I don’t pay enough attention to the mainstream media to get bogged down in the minutiae.

- To an extent, a pandemic response must be political, since our reactions revolve our attitudes to freedom and to protection.

Statists (Labour voters?) believe in a “one-size-fits-all” approach, and that the State must know best.

- Strangle, those who believe in big government have been the most critical of our own.

Utilitarians (Liberals?) believe in the greatest good for the greatest number, even if this means sacrificing some (the greatest?) members of society.

Libertarians like myself believe in individual freedom and personal responsibility above all else.

- People should be encouraged/incentivised to behave well, and more importantly, should not be bailed out when they do not.

I think we won’t know which countries did badly and well for years and that the true measures of success and failure are the macro ones:

- Excess deaths

- Medium-term impact on GDP

The UK didn’t have a good hand, to begin with:

- London is one of the great international travel hubs

- We have a lot of ethnic minority people

- And a lot of overweight people

Things don’t look great for the UK at this point, but they might look better in a couple of years.

For me, there are five real questions to answer:

- Why was lockdown not imposed a couple of weeks earlier?

- The UK was behind most of Europe and could see what was happening, yet the Cheltenham festival and a few international football and rugby matches still went ahead.

- An early shutdown appears to be linked to avoiding spread between regions.

- Why were “bed-blockers” released from hospitals to potentially infect care homes?

- This has clearly had a terrible short-term effect, though it’s possible that it has merely brought forward deaths from next year or the year after.

- Why the dithering over masks, which might have helped from the start?

- There were also delays over ramping up testing and getting a tracing app in place.

- Could the messaging have been clearer (it has been confusing to some, though not to me)?

- Given the difficultly of policing every rule in a liberal democracy (especially in the age of instant video on social media), it was always likely to come down to “common sense” at some point in the cycle.

- Unfortunately, common sense is nowadays very culturally specific, and no longer common in the sense of shared by all.

- Was government advice guided by “the science” throughout?

- Or did we start by following the science and then move towards following the money as the economic consequences of lockdown became clear?

There is probably some truth in the argument that the UK response has been too centralised (in comparison to “more successful” countries like Germany and South Korea), but once again, I would note that most of the people who make this point are in general big fans of centralisation.

On the economic side, I think the UK government has if anything been over-zealous and over-generous.

- At the same time, there are gaps – I never expected to see a Tory government give away £190 bn without me personally being eligible for any of it.

Once again, the medium-term impacts will count for more than the short-term ones.

Conclusions

It might be that we will look back on the lockdown as a massive overreaction.

- But it’s easy to understand why during the fog of war, the government would prefer to err on the side of caution.

It’s also still hard to visualise the world six or eighteen months from now.

- But I expect some behaviours to change, at least until we have a vaccine (or a reliable treatment).

Unlike a significant proportion of the younger population, I remain clear that I don’t want to catch this thing.

- The experience for a lot of people is much worse than flu, and there are poorly-understood long term impacts.

Since the lockdown was eased, I’ve been to a few pubs and restaurants, but things are quiet at the moment.

- I have no plans to go to concerts, attend live sport (football), or catch a plane (or possibly a train).

- And if a venue I’m at becomes crowded, I will leave.

Until next time.