Weekly Roundup, 20th July 2020

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup with a look at risk aversion.

Contents

Risk aversion through a crisis

Joachim Klement looked at risk aversion, starting with the classic test:

- When asked to choose between a safe return and a gamble (with potentially higher returns, but the same expected value), most people choose the safe return.

- But when asked to choose between a guaranteed loss and the chance of losing nothing (or possibly losing even more) most people choose to gamble.

This risk-seeking behaviour in the face of (potential) losses was also seen after the Covid crash (when people suffered real losses).

When investors got hurt in March, they tried to make up their losses as fast as possible. This meant doubling down and in many cases buying leveraged investments like stock options.

The problem is that the people most likely to lever up are those least likely to handle a second loss well.

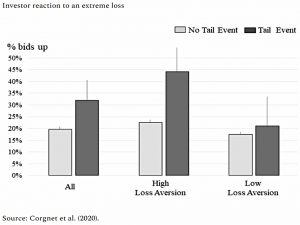

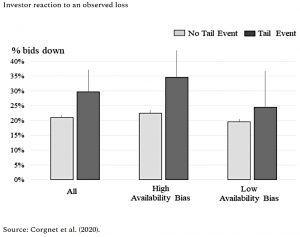

Joachim looked at a new study where subjects played a game where they made small profits or losses in 298 out of 300 cases.

- In the other two cases, they suffered catastrophic losses (more than 50% of net worth).

Compared to investors who did not experience such a black swan event, more investors increased their investments after the event. And the investors who levered up the most were the investors with the higher risk aversion.

In contrast, those who merely observed the crash but didn’t lose any money themselves became more defensive and decreased their investments.

- Their defensiveness increased in proportion to their tendency to overweight the chances of a recent event from occurring again (recency/availability bias).

Joachim concludes:

You can only learn so much about investing from a book. You have to be invested and experience markets first-hand with your own money to understand how a crash feels and how elated and greedy you can become in a bull market.

A lot of people have just experienced both for the first time.

- But as the experiment shows, the reaction to a crash that one participates in is not necessarily the right one.

Psychological traps

In the FT, Madison Derbyshire was also reporting on psychological traps.

The desire to act in a crisis is deeply embedded in our psychology. But investment

behaviour experts warn that this instinct is our own worst enemy when it comes to

money.

She was writing about risk aversion – the need to protect ourselves in a crisis, which leads to selling assets which have already fallen – but also about the bias to action, the need to do something (anything).

Investors who trade more frequently have worse long-term outcomes than those who trade infrequently or not at all. Investors who retreat from the market in a downturn rarely time their re-entry correctly, missing out on the recovery.

The trick is to do what’s uncomfortable. She quotes Greg Davies, head of behavioural science at Oxford Risk:

The right thing for your longterm goals is always emotionally uncomfortable for the present self. This gets dramatically exacerbated during times of crisis.

So stop looking at the value of your portfolio.

- The more often you check, the worse the decisions are that you make.

And stop trading from that sexy phone app.

- Other tips from the article include price-checking only on Saturdays and using a three-day wait rule on all trades.

You should also keep an investment/trading diary, logging the reasons behind all the trades that you make.

Tech breakups

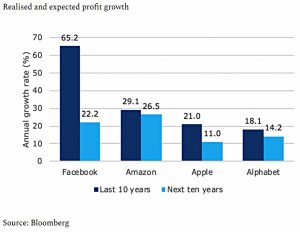

Our second article from Joachim Klement looks at the future growth in profits priced into the valuations of Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Alphabet.

- These valuations would be threatened by any anti-trust action, such as breakups.

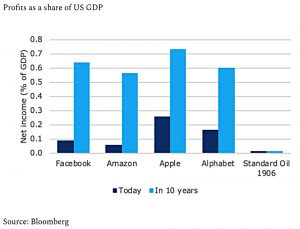

Relative to US GDP, the profits of the tech firms already greatly exceed those of Standard Oil in 1906, before Rockefeller’s firm was broken up.

- If the tech firms are not broken up in the next ten years, the profits relative to GDP will become extraordinary.

If these companies would get into trouble, the profit decline would have the potential to push the US economy into recession. If we let these companies grow to that size, they can blackmail the US government and the Fed to provide them with any kind of support their bosses feel necessary.

They will become not only too big to fail but too big to lose money.

Joachim feels therefore that breakups are inevitable, and thus so are lower growth rates and share price crashes.

- The big question, of course, is when.

Value

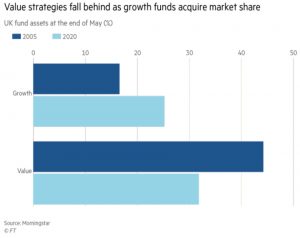

Madison Derbyshire’s second article looked once more at the death of value investing.

- She drew parallels between Tony Dye (the Dr Doom of the 1990s tech boom, sacked weeks before the market turned) and Neil Woodford.

Now Mark Barnett, Woodford’s protege at Invesco, has also bitten the dust.

Value has long been popular in the UK, which has a large supply of dividend-paying companies like miners and financials.

- But the tide has turned, and growth is catching up.

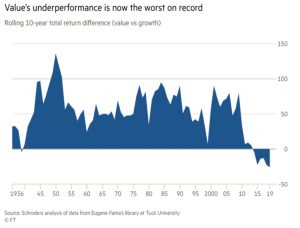

This is not surprising given the chronic underperformance of value, which is undergoing its worst run on record.

- A decade of very low interest rates hasn’t helped, and neither has the dominance of capital-light tech firms.

The pandemic-driven dividend cuts of recent months – which remove the “getting paid to wait” justification of die-hard value investors – have made conditions even worse.

- And it’s hard to see things improving in the short term.

Productivity

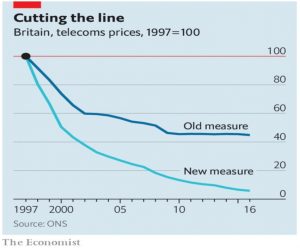

The Economist suggested that new stats from the ONS might help to explain the UK’s long-standing productivity problem.

- We have lagged the rest of the world for more than a decade.

The most popular explanation was that low wage inflation and a job culture which makes it easy to hire and fire people meant that UK firms leant on cheap labour rather than investing in productivity-boosting machinery.

- But note the ONS has published new data on telecoms prices which provide an output boost to a very large sector of the economy.

Three years of work with industry insiders and academics have led statisticians to better incorporate widening network coverage and faster download speeds. The biggest changes are in how the ons proposes to weight data usage against older services such as voice calls and texts.

The old index was base on revenues rather than usage volumes.

- The new index shows that prices fell by 95% from 1997 to 2016, rather than by just over half.

Which in turn means that output (deflated by these new price changes) grew close to eight times faster than was previously thought.

- We’ll find out the impact on the wider economy in ONS numbers due in October.

Corporate Defaults

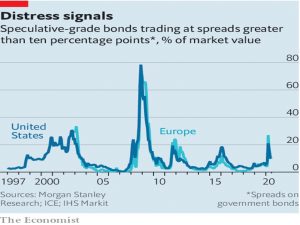

Buttonwood worried that more corporate defaults are on the way.

- Famous names like M&S, Ford, Renault and Kraft-Heinz have had their bonds demoted tp junk status (becoming what used to be called fallen angels).

At the same time, government support during the pandemic risks the creation of a new wave of zombie firms that will not die.

Since the Fed announced that it would buy corporate bonds, yields on the best credits (in tech and healthcare) have moved closer to those on government bonds.

- But there are still around 10% of bonds trading at distressed prices (10% more than govies).

This default cycle will be more industry-specific than the one following the recession in 2008-09. Think carmakers, oil firms and retailers. Airlines and hotels may be permanently scarred by changing consumer behaviour.

The historical record shows a rally in bonds follows a recession and is then in turn followed by a peak in defaults.

- Given the speed of this recession and recovery, we shouldn’t have long to wait.

Barclays Robo-advisor

In FT Advisor, Rachel Mortimer reported that Barclays has launched a robo-advisor, quite a few years after everybody else.

- It looks to be a rebadged version of the Scalable Capital offering.

This is one of the more interesting robes (with algorithms and risk management and such) but unfortunately not one of the cheapest.

- The Barclays version is even more expensive, with a 0.95% pa management charge (+VAT) and another 0.25% to 0.45% for the underlying investments.

That’s a scary total of between 1.39% and 1.59% pa.

- The Plan & Invest service is restricted to customers with at least £5K to invest, but at those prices, I think that everyone should give it a swerve.

Quick Links

I have five for you this week, the first three of which are from the Economist:

- The newspaper looked into the unexpected consequences of the UK government’s Future Fund

- Reported that NBC is considering ads on its streaming service

- And explained why a lot of people like Vietnam

- Alpha Architect looked at Left Tail Risk and Momentum

- And examined how to reduce Estimation Error in Mean-Variance Optimization.

Until next time.