Economics Manifesto – New Savings Culture

Today’s post is about a report issued earlier this month by the Policy Exchange. It’s a 61-page report with wide-ranging recommendations across the UK economy, but we’ll focus on the ten pages covering the savings culture, and how to build a capital-owning democracy.

Contents

Policy Exchange

Policy Exchange (PX) describes itself as the UK’s leading think tank. It’s an educational charity which aims to “develop and promote new policy ideas which deliver better public services, a stronger society and a more dynamic economy.”

They are “completely independent” and don’t take commissions. All research is “empirical” and they claim to work across the political spectrum. That said, they don’t reveal who their donors ((They gave £2.5M in2013)) are, and they are rated D for funding transparency by WhoFundsYou.

The group was founded in 2001 by supporters of Michael Portillo, and Michael Gove is an ex-chairman. We can assume they are towards the conservative end of the spectrum, but on the modernising wing of the Tories.

PX operate in three main areas:

- Jobs and Growth

- Poverty and Social Mobility

- Public Services

Ideas they have been responsible for include:

- Directly elected police commissioners

- The pupil premium

- Free Schools

The problem

The Economics Manifesto frames the problem it is trying to solve in terms of inequality, and in particular the role that asset ownership plays in inequality. According to policy exchange, “ownership of assets is as important as wages in generating inequality, but the distribution of savings is currently even less equal than income.”

Their proposals are designed to “create a capital owning democracy, to ensure saving isn’t only the province of the rich. Everyone should share in the benefits as the economy grows.”

The current situation

The analysis begins with Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century. However you feel about his data and his methodology, Piketty’s assertion that capital grows faster than wages and consumption wasn’t much of a bombshell for me.

You can only become a rentier if you are confident that the returns on your capital will exceed your required consumption. Unless there are sufficient opportunities to produce an “excess” return, you won’t be able to give up the day job. More simply put, capitalism depends on their being (excess) returns from capital.

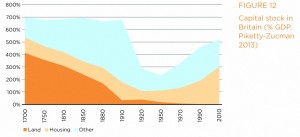

Moreover, in the UK, the recent returns to 19th century levels of capital (compared to GDP) are mostly accounted for by the growth in value of housing, which has replaced land in the 18th century breakdown.

Looking to the future however, automation could mean that Piketty’s predictions come true. If jobs are replaced by robots, the benefits of future growth would – as things stand – accrue to the owners of the robots. The PX response to this is make sure that more people have the capital to own a robot.

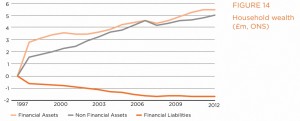

At the moment, UK savings rates are low and wealth is unequally distributed. ((The ratio between top 10% and the bottom 10% is 10 times bigger for wealth than for income.)) Only 15% of households own shares and 20% own premium bonds. A quarter of households have no private pensions.

Things have been getting worse since the 1990s. However, 64% of the population still own their property outright or with a mortgage.

Problems with saving

PX offer a number of possible reasons for Britons’ unwillingness to save:

- short-term thinking

- the welfare state

- the rising cost of generous (DB) pensions

- ease of borrowing to spend today

- tax disincentives to save

- calibration to the lower life expectancies of earlier decades

- housing supply shortage (planning rules) making property (appear to be) the most attractive way to save

The last point is the one they focus on. House prices are up by a factor of 50 over 50 years, double the inflation rate and more than a third higher than the rise in earnings. They haven’t beaten stocks though, as the graph shows. The FTSE excludes dividends and the house price index excludes maintenance costs, so stocks are well ahead in reality.

The benefit of property as a savings vehicle is the monthly “nudge” of the mortgage repayment to contribute. The downside is the increasing bet against an improvement in housing supply (a relaxation of the planning laws) and wealth illiquidity.

Housing wealth is greater than pension wealth for the bottom 70% of the population, but less than 2% of households use equity release to take advantage of it.

Falling interest rates

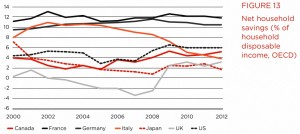

Real interest rates are at record lows, but they have been falling since the end of inflation in the late 1970s. The bond markets are predicting that the “normal” rates of the 1980s and 1990s won’t return for decades, if at all.

Demographics and the potential for continued low inflation support this. While these conditions imply low investment returns, that in turn underlines the need for increased savings.

Recommendations

The PX report has five recommendations to boost savings:

- A Bonus ISA to accommodate windfalls (inheritance, house sale, redundancy payment), based on the roll-up of unused ISA allowances from earlier years.

- This is a good idea, and the use of a lifetime contribution limit should also be applied to pensions, instead of the unfair LTA. However, the proposed initial cap on the Bonus ISA of £10K makes it almost useless – this is 8 months of normal contributions.

- Private-sector Premium Bonds – prize-linked savings are popular, particularly with those with low incomes and /or low savings.

- Another good idea, although there are no details on how the mix of “prizes” and “savings” might work. Using the private sector will stimulate the experimentation necessary to hit upon a winning formula, but leaves the product open to reputational risk on excessive corporate profits.

- No-risk stakes in RBS and Lloyds: anyone on the electoral register with an NI number can apply for shares at no up-front cost (paying only at the time of sale).

- A third good idea, though the window is closing as the government gradually sells its stakes into the market. The scheme includes a refund if the share price fails to rise over 10 years.

- Make auto-enrolment compulsory and (gradually) increase the contribution rate from 8% to 12%.

- It’s hard to argue against this. PX are batting four for four.

- ‘MyFund’ welfare accounts – segregated National Insurance contributions with allowance for overpayments by employees. Unemployment benefits would be withdrawn from them, as would training costs. Any balance at retirement would be added to the pension.

- This one is not so good. It’s basically another workplace pension option, but one that can be substantially depleted before retirement. It’s unlikely to be popular, ((It’s voluntary and has no tax advantages so the SIPP and the ISA will be preferred)) and adds to the already rapidly increasing costs of the state pension.

One notable ommission from the list is any proposal to reform the equity release market so that housing wealth becomes more accessible to pensioner owners.

Conclusions

The majority of the proposals contained in the report are sensible and would be of benefit to all savers. However, their primary purpose is to get poorer members of society to save more.

This is a laudable aim, but the report’s recommendations are unlikely to achieve it (beyond the compulsory workplace pensions). In common with all similar proposals, the PX report acknowledges the existence of the elephant in the room, but does nothing to shift it.

Our current welfare system provides no incentive for the less well-off to make provisions for their own future, since the state will provide instead.

The new triple-locked ((The pension will rise each year by the highest of inflation, earnings or 2.5%)) state pension is £8K per annum, and there is pension credit and housing benefit available beyond that. Healthcare is free. Against that, anyone with more than £10K is capital assets loses some of this entitlement.

To persuade people to save for the long-term, you need to convince them of three things:

- that they will be around to benefit

- that the amount they can save will be significant

- that the rules they are saving under will still be there to allow them to benefit

This in turn requires three things:

- An all-party committment to stop tinkering with the pensions system – declare the rules for the next 50 years and be done with it. ((It should be possible to build-in increasing longevity etc.)) Any future changes should affect only future savings, not any decisions already taken by a saver.

- A programme of financial education which starts in school and continues through to retirement. ((This needs to show that people can save enough to make a difference, and that they will live long enough to enjoy the benefit))

- Regular financial health-checks throughout a person’s life, to make sure they are still on track for their goals and indeed, that their goals remain appropriate and achievable.

Constant introduction of minor rule changes and new products won’t make the poor save. Young people in particular have no faith in the traditional approach to building wealth for retirement, and only education can change this.

Until next time.