Weekly Roundup, 31st March 2015

We begin today’s weekly roundup in the FT, with the Since You Asked column.

Contents

Effects of QE

This week the column was about the effects of QE. John McDermott wrote about Scott Minerd of Guggenheim Partners’ argument that QE is making us poorer. Minerd points to a Bank of America forecast than nominal global growth will fall this year for the first time since 2009. But nominal growth is not usually used, and the OMF predicts real global growth of 3.5% in 2015.

Minerd also believes that QE has led to “sub-optimal allocation of capital and investments, which will result in lower output and lower standards of living over time.” McDermott points out the importance of comparing QE with the “not QE” scenario.

The BoE is “near” certain that asset prices and output have been increased by QE (though they would say that, since it is their policy). Research from Liverpool and Bath universities finds that QE was initially protective, but has not stimulated growth in the long-run.

QE has increased asset prices and therefore wealth inequality, but there is no evidence that it is behind low interest rates and depressed real wages. Interest rates have been falling for decades, and real wages peaked thirty years ago. Productivity is the real underlying driver and should be unaffected by QE.

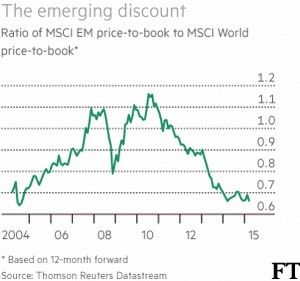

Emerging markets

John Authers advised against diving into emerging markets, which look cheap again. They are trading at 65% of the price-to-book ratio of developed markets, the biggest discount for 22 years. This a big change from November 2011, when they traded at a premium.

The problem for John is that emerging stocks carry extra risk. Growth has slowed, the dollar has risen and oil has fallen, and if the Fed raises rates that will make things worse (the dollar will rise again). Brazil, India, Indonesia, Turkey and South Africa have all run large current account deficits, and suffered when the Fed began to taper QE in 2013.

Since then India has improved, but Russia has declined. Brazil is in the worst state: 90% of external borrowing is in dollars, exports have been hit by falling commodity prices and the political situation is dire. Chile, South Africa and Malaysia have similar problems.

John has concerns about how to invest. Debt has been bid up by yield-hunters, and the recent sell-off in stocks has been very discriminating, with the best stocks remaining on the highest valuations (or even privately held). China and India are less cheap than other markets. John recommends a phased approach with a view to the long term.

Man vs machine

It’s a quiet week in the run-up to Easter, so I have time to go back to an article from earlier this month. Tim Harford wrote about the possible reactions to increasing automation, comparing the setting of man against machine with the Luddites of two hundred years ago.

Tim began by correcting a misunderstanding about the Luddites. They didn’t believe that the spinning and weaving machines they destroyed would lead to mass unemployment. They were worried that their own skilled craftsmen jobs would be displaced by simpler jobs for less qualified workers. Power would shift to the factory workers who owned the machines. It was a form of trade union activity – “collective bargaining by riot”.

This anxiety has now returned, as software and robots begin to threaten skilled and middle-class jobs once again. Journalists like Tim are particularly worried (in part by unpaid bloggers like me), and so the anxiety is making its way into the papers and journals they write for.

In fact this trend has probably been around for decades. The flat-lining of real wages over the past 30 years is partly due to technological change suppressing median wage (as well as globalisation and the decline of unions).

Tim outlines four possible interpretations:

- business as usual – technology has continuously improved since the time of the Luddites, without ever resulting in mass unemployment

- this time it’s different – robots will make many people economically valueless, and money will flow to the owners of the robots (and through taxation to the government)

- neo-Luddite – there will still be jobs, but only low-paid, unskilled ones; industries will be destroyed and created

- robots will be good for us – there will be a surge in (new) jobs as they are built and installed, and then long-term productivity gains, potentially to be shared by all

I think Tim is a little optimistic with the last option, but he’s right to point out that low productivity is currently a big issue.

My money is on option 2, which will require big changes in the structure of society for us to cope. I can foresee the introduction of a basic income for all adult citizens (something I wouldn’t have believed ten years ago). I’ll return to this in a later post.

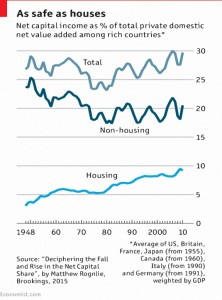

Piketty unpicked

The Economist reported on the challenge to Thomas Picketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century from a 26-year-old graduate student at MIT. Matthew Rognlie’s paper (expanded from a blog post!) has three points:

- Return on capital probably declines in the long run due to diminishing marginal returns (Piketty argues it is constant); software is a good example when compared to the giant machinery of earlier decades. Gross returns may rise as net returns fall because of the need for re-investment.

- Returns on wealth will also decline unless it is easier in the future than it has been in the past to substitute capital (robots) for workers.

- The growing share of national income from capital is concentrated in the housing sector. Non-housing wealth has been stable since 1970.

Many feel that Rognlie is underestimating the impact of technology in widening inequality. But the concentration of gains in homeowners impacts Piketty’s call for a wealth tax. It might be more sensible to reform the planning laws that limit the supply of housing.

Election jitters

Buttonwood’s column looked at the potential impact to financial markets from the upcoming general election. Before 2010, UK elections generally returned strong governments, but things have changed. Current projections suggest that the existing coalition will not have enough seats between them to govern, and nor would a Labour / SNP coalition.

A minority government is a real possibility. Legislation would be passed bill-by-bill and the annual budget would require significant negotiation. The last time this happened (in 1974) there was a new election within the year. But the rules are tougher now, and a no-confidence vote is needed.

Even if the initial result is clear, the Conservatives plan an EU membership referendum, which will not be market-friendly. A Labour victory would deter investment just as much. Markets are doing well at the moment, but it may not last beyond May 7th.

Don’t blow your pension

Finally – as reported in the Daily Mail (amongst other places) – the Department for Work and Pensions clarified this week what would happen to pensioners who run out of money after taking advantage of George Osborne’s new pension freedoms.

If they are assessed for any means-tested benefits, their former pensions will be treated as though they still exist. Housing benefit, jobseeker’s allowance, support allowance and pensions credit are all affected. So mind how you spend it.

Until next time.