Investing in ETFs

Today’s post is a follow-up to the recent article on the Meetup Experiment, and summarises the discussion around Investing in ETFs that was had at the first meeting of the group.

Contents

Meetup

Back in January 2019, I took over the organisation of a Meetup group with more than 350 members.

- You can read more about that process and experience here.

The group was called the London Passive Investing Club, and its description at the time I became the moderator was as follows:

This group is for people who manage their own passive stock market investment portfolios as a DIY investor, or want to become a passive DIY investor.

Maybe you are managing your own savings, or pensions and want to meet people with similar experiences, or perhaps you are thinking about managing your own money and need more information.

Passive investing involves buying Index Trackers or Exchange Traded Funds, which track the market indices worldwide.

Here’s the revised version:

This group is for passive DIY investors, and for those who want to become passive DIY investors.

We are primarily concerned with ETF portfolios, but people who use OEICs are also welcome.

Topic we discuss include:

- What is an ETF (exchange traded fund)?

- What’s inside an ETF?

- How do I invest in ETFs?

- What does it cost to invest in ETFs?

- What does a good ETF look like?

- What are the risks of investing in ETFs?

- How can I research ETFs?

- How do I decide on an asset allocation strategy, and construct a suitable ETF portfolio?

- Should I use smart beta / factor ETFs?

- How and when should I rebalance my portfolio?

- Are the problems of living off my portfolio in retirement (decumulation) the same as those of building up my portfolio in the first place?

You’ll notice that I answer many of these questions below.

I sent out a survey to see what the group’s interests were, and though I didn’t get many responses, the majority of members seemed to prefer ETFs to OEICs. ((Technically many ETFs qualify as OEICs in order to offer consumer protection, but most people understand OEICs to mean mutual funds / unit trusts that are not traded on exchanges ))

- The first meeting of the new group was scheduled for February 2019.

It was sparsely attended, but this is what we talked about.

What is an ETF?

We’ve written about ETFs before (here) but this article covers the same material in slightly more detail.

ETF stands for Exchange Traded Fund.

- Together with Exchange Traded Commodities (ETCs) they form the group of assets known as Exchange Traded Products (ETPs).

The simplest way to think of them is as index funds that are listed on the stock exchange.

- They are passive, pooled instruments that aim to track the performance of an underlying index (the target, or benchmark)

- But unlike regular index funds – which have a single daily price for trades – ETFs can be traded like a normal share at any point when the exchange is open.

Note that in one sense there is no such thing as passive investment – all portfolios include some element of selection and / or choice – but an ETF itself will passively track its target index and does not attempt to outperform.

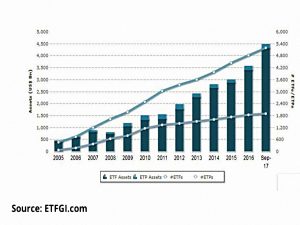

ETFs have been available in the US since 1993, but only caught on in the UK in the last decade or so.

Who needs ETFs?

All investors should use ETFs.

- They are usually the lowest cost and most flexible way to access a wide variety of asset classes.

They are the easiest way to build a diversified portfolio.

- An investor with a small portfolio will be restricted to a small number of ETFs, but more complicated structures can be adopted as funds allow.

Prerequisites

All you need to buy an ETF is a stock trading account with a broker in order to buy an ETF.

- Setting one up is straightforward, but this sometimes discourages new investors, who instead but OIECs directly from their provider.

But you would be well-advised to have already put together a few documents:

- An annual budget that includes a surplus that can be saved.

- A plan of some future financial state that you hope to achieve, and how you plan to get there.

- This should include an asset allocation strategy – a description of which assets you want to hold.

- This will depend on your risk tolerance, so you will need to determine this (perhaps by taking a questionnaire).

- Our latest series of posts on asset allocation goes by the name The Perfect Portfolio, and will be published shortly.

- Some financial statements to show where you are today – how far you have got so far with your plan.

ETFs can be held in taxable broker accounts, but you should consider a tax-shelter – a wrapper to hold the ETF inside.

- In the UK, this will normally be a SIPP or an ISA.

- As your portfolio gets bigger, this will save you money.

Sometimes the wrapper will be referred to as a platform.

- The platform you choose for your ISA / SIPP / taxable account may restrict the range of ETFs that are available.

- Before choosing your platform, you need to check which ETFS are supported.

How much do they cost?

There are four main sources of costs with ETFs:

- The underlying costs of the ETFs themselves.

- These are usually low relative to the alternatives.

- Trading costs for buying and selling ETFs.

- This is the only downside with ETFs in comparison to OIEC index funds, which don’t have transaction fees.

- For this reason, smaller investors are often drawn to starting their portfolio with OIECs.

- OIECs are also more suitable for “dollar cost averaging” strategies (regular monthly investing) with small amounts.

- Note that the government tax on share transactions (stamp duty, at 0.5%) doesn’t apply to ETFs.

- But note also that this doesn’t mean that ETFs are exempt from paying stamp duty when they buy UK stocks.

- The bid-ask spread

- Ongoing costs from the platforms and wrappers in which you hold the ETFs.

ETF costs vary widely, from as little as 0.04% for a FTSE-100 tracker to around 0.75% for a more exotic asset class (Private Equity, or Emerging Markets Infrastructure, say).

- Some platforms – usually those provided by the main ETF brands – will include a “Core” range of six to twelve ETFs that are particularly cheap (0.07% to 0.25% pa).

This can be useful, but it’s the overall cost of the final portfolio that counts.

- Those who want exposure to long-term potential growth across all asset classes and geographies will need to use additional, higher-cost ETFs.

Trading costs range from £5 to £12 for the mainstream brokers, though it is possible to pay more.

- This means that minimum cost-effective trade sizes are in the region of £3K to £5K.

Platform costs can be zero for ISAs and for taxable accounts, but all SIPPs levy a platform charge.

- Larger portfolios will need a platform with a fee cap.

In recent years, AJ Bell YouInvest (£100 pa) and Fidelity (£45 pa, but for a restricted list of ETFs) have been the cheapest platforms.

With say £50K to invest, it should be possible to keep the ongoing costs of a well-diversified portfolio below 0.50% pa.

- The first year costs would be closer to 0.70%, as the initial purchases need to be made.

What’s inside an ETF?

There are two kinds of ETF

- Physical and

- Synthetic – also known as derivative-based.

Physical ETFs hold the assets from the index they are tracking – stocks, say.

- This is very safe, but can also be also expensive, as they need to buy and sell assets as their prices change (which in turn changes the composition of the index).

There are two kinds of physical ETF – those that use full replication (holding all the constituents of the index) and those that use “optimised” replication (holding only a sub-set of the constituents).

- The latter are usually cheaper, but may not track the index quite as well.

- Bond ETFs often use sampling, as some of the bonds in the relevant index might be very illiquid.

- And trackers of very large stock indices may not hold all of the constituents.

Synthetic ETFs hold a basket of quality assets (usually blue-chip stocks from the local main market, such as the London Stock Exchange) and use a “swap” contract with a bank to transform the returns from this basket into the returns of the index that the ETF tracks.

- This is usually cheaper than a physical ETF, but introduces counterparty risk.

- If the bank providing the swap contract fails, then instead of the returns from the desired index, you might end up with the returns from the blue-chip stocks.

Note that even physical ETFs in theory expose the investor to counterparty risk from the investment manager.

- But in practice the assets will be ring-fenced.

There was a lot of talk about the risks of synthetic ETFs a few years ago, but most of this was overblown.

- There’s very little risk that you will lose your money if a counterparty goes bust, and there are mechanisms in place to ensure that the gap between the desired returns and the blue-chip returns remains small.

What does a good ETF look like?

A good ETF has four main features:

- it comes from a reliable provider

- it’s big enough (in terms of assets / market capitalisation) to be liquid (easily and cheaply traded)

- £100M is often taken to be the minimum size for a “good” ETF, but for some asset classes you won’t get close to that.

- You can also look at the bid-offer spread (in percentage terms) and the daily volume of trading to gauge the level of liquidity.

- Note that the liquidity of an ETF is more complicated than that of a regular share – the liquidity of the underlying securities tracked by the ETF is also relevant.

- it has low running costs (annual charges) for the asset class that it covers

- it has a track record of sticking close to its target index (low average tracking error and low volatility of tracking error).

What are the risks?

The main risk is that of a synthetic ETF not delivering the promised returns because the counterparty runs into difficulties.

There have also been fears that the high-liquidity of ETFs is a poor match for low-liquidity markets (eg. some areas of the bond market after ten years of QE and low interest rates).

- But there have been no big failures to date.

Leveraged ETFs (with double or triple the exposure to the index, usually available in both long and short flavours) introduce some extra risks.

- Because these instruments are re-based at the end of each day, their tracking can be poor and they are unsuitable for long-term investors.

Where can I find out more?

Researching ETFs is pretty easy.

- Your platform will have a lot of information on the ETFs that they offer

- In addition you can use websites like justETF, FE Trustnet and Morningstar.

Quality blogs like this one can also help.

Conclusions

For most private investors, the main risk with ETFs is in not owning them.

The three things that private investors can control that will have the greatest impact on their long-term returns are:

- costs

- taxes and

- asset allocation

ETFs tick all the boxes:

- they are usually the cheapest way to access an asset class

- they are compatible with the key UK tax wrappers (SIPPs and ISAs)

- they allow you to access a wide variety of asset classes and geographies

They are one of the most useful innovations of recent decades.

- So go and get some.

Until next time.