Irregular Roundup, 13th November 2023

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup with US exceptionalism.

Contents

US exceptionalism again

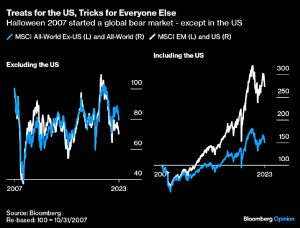

John Authers’ Halloween newsletter reminded us that in 2007 the market peaked at Halloween.

- Sixteen years later, markets outside the US remain below that peak.

US stocks are triple what they were.

Valuations are a big driver.

- Halloween 2007 was the smallest gap between US and world valuations, but now we’re back at dot com levels.

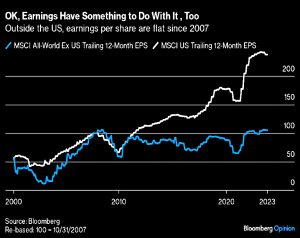

The other reason is earnings.

US earnings per share have more than doubled over the last 16years. For the rest of the world, they’re barely changed.

A big internal market and low corporate taxes help, but US firms outperform those in nominally faster-growing economies.

Virtually all the narratives that might explain this are discomfiting. They fall into the left-wing school — that holds that US companies have been allowed to merge, jack up margins and exploit workers — and the libertarian or Austrian school, which would hold that endemic interference with markets hasled to malinvestment, moral hazard, and a bubble that must soon blow up.

There’s also the tech basis of the US and the Magnificent Seven.

More to the point, what comes next?

- Are we looking at a repeat of the dot com collapse?

Surely a regime of treats for Americans and tricks for everyone else can’t endure much longer.

Zero-sum

Hat tip to Davis Stephenson, who pointed me at an article from Ian Leslie on Zero-sum thinking – a topic we looked at a few weeks ago.

Dividing a cake is a zero sum game; if you get a bigger slice, mine will be smaller. A non-zero sum game is one in which the cake magically grows as you’re dividing it. Science is a non-zero-sum game – everyone in the field gains when knowledge is advanced.

I should declare an interest here – I’m a very competitive person, and I have a preference for zero-sum forms of conflict resolution, where I win and the other person loses.

- I make an exception for service contexts (music, restaurants, medicine), and even I know that zero-sum doesn’t work in some situations.

But the fundamental basis of economics is handling scarcity – there isn’t enough of the good stuff that people want to provide for everyone.

- And there usually isn’t a magic wand to provide more stuff, so we need to work out the best way of allocating it.

Price is the best way, and intervention in free markets is usually counter-productive.

Back to Ian.

In the Malthusian mindset, there was no point trying to make the poor better-off, because then more of them would survive and fewer deaths inevitably meant lower living standards for everyone else.

Poor is an emotive term, but if you replace it with non-productive, the argument becomes a lot more nuanced.

Done right, economic growth means that the better off others become, the better off we are.

“Done right” is doing a lot of work here, and there will always be exceptions inside the “others” group.

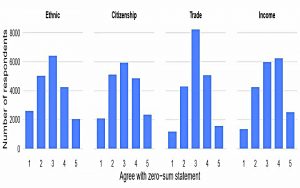

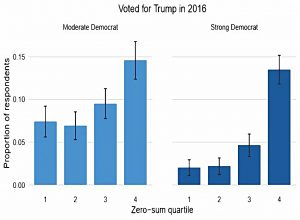

Ian reports on a Harvard study that asked 20K people whether they thought gains for one group came at another group’s expense.

- They used these responses to construct a zero-sum index and then matched that to personal data about political attitudes,income, age and family background.

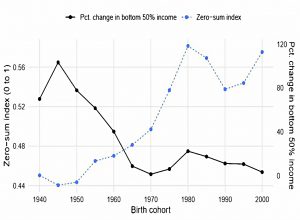

Interestingly, young people are more zero-sum than old people (a result we came across last time).

- The economists explain this through the state of the economy when people are young.

The post-war economy delivered on President Kennedy’s promise that “a rising tide lifts all boats”. In the 1950s and 1960s, some Americans got a lot richer than others, but all Americans gained. Good times tend to breed non-zero-sum mindsets. But when lower or middle-class incomes stagnate, a zero-sum worldview finds more purchase.

It seems that young people today feel times are tough, though things are clearly much better than they were in say the 1980s, or the golden 1960s (I lived through both decades and it’s not a close-run thing).

There’s clearly a relationship with per capital growth to the age of 20, regardless of how much about life that measure fails to capture.

The politics is interesting, too.

The mindset is more associated with left -leaning political views. High zero-summers are more likely to favour policies that redistribute income from the wealthier to the less wealthy, and to back affirmative action for African-Americans and women. But they were also likely to favour more restrictions on immigration.

Ian sees this kind of thinking as responsible for the rise of Trump.

Left-wingers tend to assume that there is a fixed amount of wealth to go around, and that the fundamental problem of modern economies is therefore one of distribution. Some of the attitudes we group under ‘cancel culture’ or ‘woke’ stem from a view of society in which there is a limited amount of status or income to go round and some must “make way” for others.

Not much of this is good, but if what we need to get rid of it is strong per capita GDP growth, we might be waiting a long time.

Active vs passive

Another hat-tip to The Investor over at Monevator, who pointed me towards a post by Conor Mac on Investment Talk called Why don’t you just sell all your stocks and buy ETFs, you’ll probably have better performance?

Conor asks the same question that I do whenever I attend an investor group or conference:

I question why individuals bother buying individual stocks, where the odds of beating the market are stacked against them, instead of buying the market and living a relatively carefree life.

And he gives the same answer:

The little white lie we all tell ourselves as individual investors; that we are different, and despite the majority who will inevitably fail, we will beat the market.

Although I would love to consistently beat the market, my personal goal is less ambitious:

- I want to keep pace with the market but with lower volatility.

There are ways to approach this, which this blog attempts to explore.

Inflation expectations

Joachim Klement compared inflation expectations (and explanations) between economists and ordinary people.

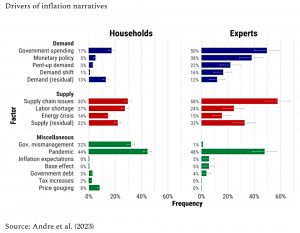

Peter Andre and his colleagues surveyed more than 10,000 US households and more than 100 experts about the recent surge in inflation and its causes.

Joachim is a bit of a cynic when it comes to inflation:

I am on the record for criticizing all existing theories of inflation (whether they are monetarist, Keynesian or fiscally driven) for being based on rational expectations and discounting future cash flows into the present.

This is of course what I do personally, but I know from my own interactions with others that I am in a tiny minority.

The key drivers of the inflation spike in 2021-2023 according to experts was excessive government spending (in particular government spending during the pandemic), supply chain issues and monetary policy.

I agree with this analysis.

If you ask households what caused inflation, they will tell you it was the pandemic, government mismanagement, supply chain disruptions and labour shortages. In essence, households form their inflation expectations based on what they experience in their everyday lives.

This is dumb, but we are stuck with it.

- And it has implications for theory.

As long as central bankers insist on trying to guide inflation expectations by providing forward guidance about future rate hikes or cuts and similar abstract measures only intelligible to experts, they will fail to influence real life inflation through managing inflation expectations.

I tend to agree with Joachim, but I appreciate the guidance, and I’m not sure how to get ordinary people to understand what’s really going on, or even to care about the big picture.

- People care about their own situation, right now, and they’ll vote for anything that they think will improve it (or will hurt people that they hate).

Lloyd’s of London

In Investor’s Chronicle, Julian Hofmann looked at a new IPO which is hoping to revive interest in the Lloyd’s of London market.

- Returns from insurance can be decent (say 10% on average) but they are lumpy and there are serious drawbacks to investing directly (£100K to £1M minimum investment, no tax incentives other than IHT exemption).

People my age also remember the Lloyds scandal of the late 80s and early 90s, when a lot of natural and manmade disasters led to bankruptcy for the Names who at the time had unlimited exposure.

- Liability is limited these days, but the prospect of a 100% loss remains bracing.

Now a SPAC (special purpose acquisition vehicle) is launching with the objective of attracting retail investors to the market.

Financials Acquisition Corp (FNWR) has been flagging a possible £500mn offering that will engineer a listing on the stock exchange via a reverse takeover of London Innovation Underwriters (LIU). The newly created entity will then use the proceeds to invest directly in acquiring a book of Lloyd’s market syndicates.

There are other ways to invest already:

The simplest route now is simply to buy shares in specialist reinsurer Beazley (BEZ),whose own underwriting of cyber-security reinsurance has been one of the most successful areas on the market.

It will be interesting to watch how FNWR develops.

Quick Links

I have seven for you this week, the first four from The Economist:

- The Economist wrote In praise of America’s car addiction

- And asked Are politicians brave enough for daredevil economics?

- And said The fall of WeWork shows the deepening cracks in property

- And reported that Silicon Valley is piling into the business of snooping.

- Alpha Architect looked at The Performance of Major Private Equity/LBO Firms

- UK Dividend Stocks explained how to diversify a defensive dividend portfolio

- And The Spectator wrote about The beauty of mid-range products.

Until next time.