Irregular Roundup, 18th September 2023

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup with house prices.

US house prices

The Economist wondered how US house prices could still rise when mortgage payments are at their highest since the 1980s.

- Mortgage rates are up from 3% to 7% on the back of Fed rate hikes, doubling the monthly payment on the median home by the median family.

But after a brief decline, house prices have rebounded to record highs.

Although demand for homes has fallen as rates have risen, the supply of properties has fallen almost in lockstep. Homebuyers typically obtain fixed-rate mortgages for 30 years—unheard of in most countries but viewed almost as a constitutional right in America.

US mortgages are securitised by two government-backed firms – Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

The problem (for the economy) with long-term mortgages is that nobody who is locked into a rate that is half that in the market is likely to sell.

- Fixed-rate mortgages also slow the transmission of the impact of interest rate hikes on the economy.

The decline in transactions, all else being equal, ought to hurt the economy, dampening housing-related activity, with less money spent on remodelling, new construction, furniture and so on.

But instead, people have been fixing up their existing homes, in part because of remote working.

- There’s also been a switch towards new builds, which allow lower interest rates through an up-front payment.

It’s possible that the market will cool if rates stay higher for longer, but the reverse is also true:

Strong housing-market activity contributes to an overheating economy.

And the unaffordability of housing could push more people into renting, driving up rents and thereby propping up inflation.

Danish mortgages

The newspaper also looked at the Danish mortgage market, where rising rates have caused problems.

- In contrast to the US, British mortgages are usually fixed for just a few years; the same is true of Sweden.

But Denmark offers a middle ground:

Homebuyers can borrow at 30-year fixed rates, yet there is no problem of “locked in” homeowners because a seller can end a mortgage by buying it back at its market value, which falls when rates rise, thereby cashing out the value of their interest-rate fix.

They can also transfer their mortgage to the person they sell to.

As you would expect this leads to a more dynamic market:

In the first quarter of 2023 housing transactions were down by only 6% on a year earlier, compared with 22% for existing homes in America.

This sounds like a good system, and it involves no government-backed agencies (as are needed in the US).

UK Tax

In the FT, Emma Agyemang said that we should be prepared to pay more tax to whoever wins the next election.

- As we noted last week, Labour has ruled out a wealth tax and increases to CGT or property taxes.

Some Conservatives are putting pressure on the PM to cut taxes before the election, with the abolition of IHT as a prime candidate.

- The IFS recently concluded that there is no room for tax cuts without cuts to services.

This seems obvious to me, but any mention of a reduction in the size of the state now appears to be forbidden.

Pledges made so far by Labour include the abolition of the non-dom scheme, VAT on private school fees and the end of the carried interest tax break used by private equity.

- Labour has also said it will restore the LTA on pensions, but protection for previous contributions will presumably need to be offered.

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt has been damping down tax-cut expectations:

[I must] double down on inflation and will not pump billions of pounds of additional demand into the economy.

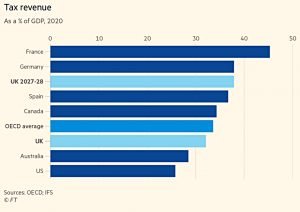

The current UK tax burden is the highest since the post-war hangover and is predicted to rise to 38% of GDP by 2027-28.

The increased take is mostly effected via “stealth” taxes — notably the freezing of allowances and thresholds at which tax is paid — from April 2022 to 2028. This “fiscal drag” approach is especially potent at a time of higher inflation.

The 45% tax rate threshold has also been lowered to £125K.

- This means that more people are paying the higher rates of tax.

Other freezes and cuts include IHT, CGT and the dividend allowance.

There’s no light at the end of this tunnel.

US stocks

The Economist noted that US stocks are at their most expensive in decades.

- Over the long run (since 1900) stocks have returned 6.4% pa (after inflation), whereas bonds have only returned 1.7%

From a historical perspective, buy and hold looks attractive.

Unfortunately, there is a catch. What matters today is not historical returns but prospective ones. And on that measure, shares now look more expensive—and thus lower-yielding—when compared with bonds than they have in decades.

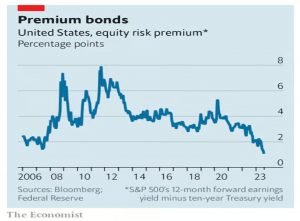

Shares a riskier than bonds, so they need to offer a risk premium (a higher return).

Estimating the return on a bond is easy: it is just its yield to maturity. Gauging stock returns is trickier, but a quick proxy is given by the “earnings yield” (or expected earnings for the coming year, divided by share price).

Over the last year, this premium has collapsed.

Both expected earnings and Treasury yields are roughly where they were in October, when share prices hit a trough. But since then shares have risen a lot, shrinking their earnings yield and bringing it closer to the “safe” Treasury yield.

There are three explanations:

Investors might believe earnings are about to start growing fast, perhaps because of an AI-fuelled productivity boom. They might think earnings have become less likely to disappoint, justifying a lower risk premium. Or they might fear that Treasuries are now more risky.

None of these options are good, with the “animal spirits” of the second theory perhaps the most worrying.

- Most likely, the squeezed premium reflects a bet on a soft landing (lower inflation without a recession) which might or might not happen.

But last year was the worst for bonds in over a century, and investors are probably still bruised.

- A preference for stocks at any price could also reflect a belief that inflation has moved structurally higher.

Higher bond yields (which also imply a lower equity risk premium) could also be here to stay:

Governments are set to issue ever more debt to cover ageing populations, defence spending and cutting carbon emissions, while central banks have disappeared as buyers.

Phillips Curve

Joachim Klement asked whether the Phillips Curve has become steeper.

- The PC dates back to the 1960s and specifies a relationship between inflation and unemployment.

One would expect an economy with lower unemployment rates to face higher inflation due to increased demand, while bringing down inflation creates an increase in unemployment.

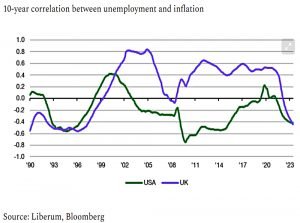

Joachim looks at the relationship through the 10-year correlation between the two variables.

- We should see a negative correlation (below -0.4).

Over the last two decades, this has rarely been the case.

- But in recent years, the correlation has turned negative again.

Does that mean the Phillips Curve has risen from the dead and is now steep enough again to be useful for policymakers?

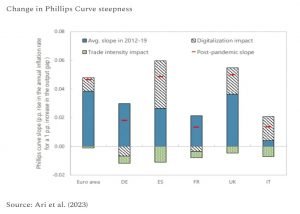

A recent study suggests two reasons for an increase in the steepness of the PC:

- deglobalisation and

- digitalisation

If the economy of a country becomes more globalised, it opens itself up to foreign labour and the link between inflation and unemployment becomes weaker.

If an economy becomes more digitalised, businesses can react more flexibly and replace workers with machines. Hence prices become more flexible, and you have bigger changes in inflation in response to a small change in employment (i.e. consumer demand).

Rising digitalisation in the aftermath of the pandemic has made prices more flexible and hence created a steeper Phillips Curve. Meanwhile, trade intensity has continued to increase a little bit creating a somewhat flatter Phillips Curve.

The net effect is a slight steepening.

A one percentage point increase in the output gap creates about 0.5% higher inflation rates in the eurozone and 1% higher inflation rates in the UK.

The output gap is the shortfall from the peak capacity of the economy.

Joachim remains unconvinced that the PC is steep enough to be a helpful theory for policymakers, and he thinks that it might be flattening again.

UK GDP

We had some good news this month when the GDP figures for 2020 and 2021 were revised upwards such that the numbers for 4Q21 are now 0.6% above pre-Covid levels, rather than 1.2% below.

The ONS said:

These revisions are mainly because we have richer data from our annual surveys and administrative data, we are now able to measure costs incurred by businesses (intermediate consumption) directly and we can adjust for prices (deflation) at a far more detailed level.

The new numbers mean that Britain is no longer the worst-performing economy in the G7. Chancellor Jeremy Hunt said:

The fact that the UK recovered from the pandemic much faster than thought shows that once again those determined to talk down the British economy have been proved wrong. The declinist narrative about Britain and its long term prospects — for which post-pandemic growth was usually cited as a main piece of evidence — is just wrong.

Quick Links

I have four for you this week:

- Mauldin Economics looked at John Mauldin’s Personal Portfolio

- Noahpinion explained How not to be fooled by viral charts

- Alpha Architect looked at Trend Following and Momentum Turning Points

- And UK Dividend Stocks explained Why Prudential plc is no longer in my portfolio.

Until next time.