The Year of Coronavirus

Today’s post offers up a few thoughts on the terrible year just passed.

Contents

Annus horribilis

Good riddance to what has to be the most difficult year in my life so far.

Since March, I’ve written eight articles about the virus and its impact on my portfolio.

- Given that a vaccine rollout is now underway, I think that we’re in the recovery phase of the pandemic.

So I’d like to revisit the issues I’ve previously considered for what I hope is the last time.

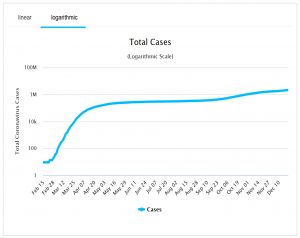

At the time I started writing this article (just before Xmas), there were 77.8M recorded cases and 1.7M deaths worldwide.

- Here in the UK, there have been 2.0M cases and 67.6K deaths.

Portfolio

Let’s get the portfolio stuff out of the way first.

- When the pandemic kicked off, I sold things that I thought would suffer the most/recover the slowest – to make sure that I had enough cash to get through the pandemic.

I go two things wrong here:

- I thought that the market recovery would take longer than it did (in my defence, I have no precedent for living through a pandemic)

- I didn’t appreciate the extent to which lockdowns and tiered restrictions would impact my spending – I over-estimated how much cash I would need and I sold too much.

I’ve been buying back in for the rest of the year, starting with the obvious stuff like China, gold and tech.

- I’ve now also unwound my underweights to Europe and the UK, and I have been adding to my thematic portfolios (tech, biotech and ESG).

After Xmas, I will be buying into the reflation and recovery trade through cyclical and travel and hospitality stocks.

- A lot of people got into this trade when the first vaccine was announced and have been well-rewarded – though the discovery of the highly-contagious UK mutant vaccine has led to a setback.

My plan is to be fully invested by April, which is the earliest that I expect the Covid restrictions to be relaxed.

At the low point in April, my (low-volatility, widely-diversified) portfolio was down 11.5%.

- At the time of writing, I am up 9.2%, which I am very happy with considering the events of the year.

The questions

Here are the questions I asked back in April:

- How contagious is the virus?

- How deadly is the virus?

- How many excess deaths should we expect?

- How prevalent is the virus, particularly here in the UK?

- When will we have an adequate testing regime?

- What is the likely path of the pandemic in the UK?

- When might we have a vaccine?

- What are the exit strategies from lockdown?

- Can we trade lives against economic loss?

During the year we added a couple more:

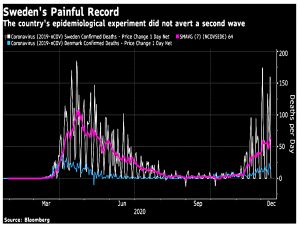

- Does lockdown work (or would the “Swedish approach” have been preferable)?

- How has the UK government performed?

Today I’ll add one more:

- Will the vaccine eradicate Covid-19?

Before we start, here’s the usual disclaimer that I’m not a doctor, or an epidemiologist – I’m just someone who likes to analyse data, and has a big interest in the economy.

Contagion

The virus is pretty contagious, and this new mutant appears to be much more contagious than the version we got used to over the spring and summer.

I’m no longer so impressed by the impact of lockdowns on the R number, but this might be down to the lower levels of compliance as the year progressed.

- Young people, in particular, appear to believe that they have already been immunised.

In the absence of a counterfactual or control group (other than Sweden, see below), we must assume that lockdowns, distancing, masks and hand washing are having some impact, though clearly not enough.

The complicating factors from March remain:

- Some of those infected show no symptoms and will likely not present to the health system

- They may still be infectious, however.

- Around 80% of those who do show symptoms have a mild form of the disease.

- These people might stay home, too

- The symptoms associated with the disease are quite varied, complicating diagnosis.

- Most are also common to lots of respiratory diseases (colds, hayfever).

What we do know is:

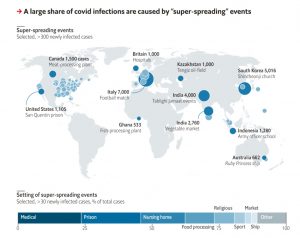

- Inside is much worse than outside, and singing/shouting/hugging is worse than chatting quietly.

- Two weeks of isolation seems to be long enough to wait out the incubation period.

- The virus is quite hard to catch – there are lots of cases from cloistering (eg religious groups) and in situations where people might have repeated exposure or exposure to a high viral load (the healthcare system, transport and shops).

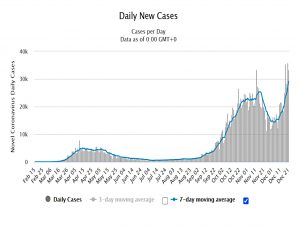

- The virus is seasonal (in the northern hemisphere at least) and a winter “second wave” was to be expected.

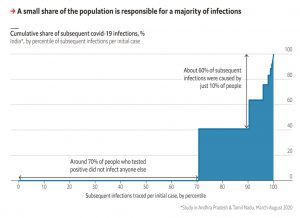

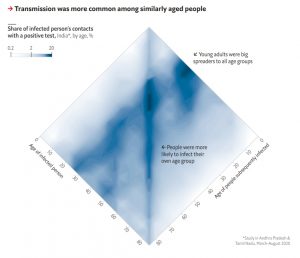

The Economist noted that a minority of people (so-called super-spreaders) are responsible for the bulk of transmission.

- It’s the Pareto principle/power-law once again.

In two Indian states, 10% of people caused 60% of subsequent infections.

Such transmission occurs most often in large buildings, while just three documented events have taken place outdoors. Risk of infection is greatest among similarly aged people.

Deadliness

This ought to be the easiest question to answer since deaths are well recorded.

But:

- Some countries count dying with Covid as well as dying from Covid.

- Some countries record only hospital deaths and not those at home or in nursing homes.

- Deaths are (at least initially) often logged against the day of reporting rather than the day of death, adding noise to the data.

- Death rates vary significantly by age (in particular), gender and pre-existing health conditions (sick old men do worst) – and possibly by other demographic variables.

The death rate for resolved cases is down to 3%, and only 0.5% of the active cases are “serious or critical”.

- I would guess that the true mortality rate is not much more than 0.5%.

The UK has dropped to eleventh in the deaths per capita table (behind Belgium, Italy and Spain).

There seem to be two factors behind both of these improvements:

- A lot of the most vulnerable people (eg. in the care homes in the UK) died in the first wave.

- The testing programme and treatment available in hospitals has improved significantly.

It might also be the case that mutations have made the virus less deadly (as usually happens).

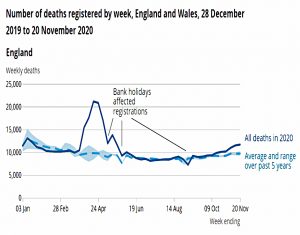

Excess deaths

We won’t really know how deadly the virus is until the pandemic is over.

- Around 600K people die each year in the UK, and the true impact is any excess deaths over this figure.

And even that is only a net impact.

Some of the trade-offs include:

- People (usually old and sick) who would have died anyway, many of them from a regular winter flu.

- People who won’t die from other contagious diseases that they won’t catch because of the lockdown.

- Varying accident rates in the home (up), the workplace (down) and the roads (down).

There are also second-order effects like increases in poverty, substance abuse, domestic violence and mental health issues – each of which would impact society’s goal of long and healthy lives.

- And people with “normal” diseases (particularly cancer) may not seek help, or may no longer be offered it.

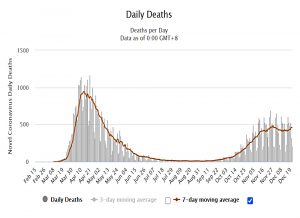

The UK had excess deaths in March, April and May, but they fell back to normal over the summer.

- Since mid-October, excess deaths have been rising again.

We have around 65K excess deaths YTD in the UK, despite all the countermeasures we have endured.

Prevalence

With the advent of a vaccine, hypothesizing about the prevalence of the virus in the community has become less profitable.

- Herd immunity is clearly not going to be our path out of this pandemic (see Sweden, below).

The key numbers now are infection rates and the trend of infections, since these determine the tier of restrictions your area falls into.

- With the emergence of the new UK mutation, this increasingly looks like Tier 4 for everybody in the near future (previously known as a national lockdown).

A given number of deaths are consistent with more than one scenario:

- Rare and deadly

- Common and not lethal to many

Most widespread testing studies have found no evidence for widespread infection, but this is complicated by the possibilities that (i) the antibodies don’t last long after fighting the infection and (ii) some young people in particular fight off the virus using T-cells, without ever producing antibodies.

Testing

Anyone can get a test now – free if you are patient, at a price if you are desperate.

There are two types of test:

- Antigens – answers whether you have the virus today

- Some countries are using facial temperatures (measured using something like an infra-red camera) to do instant tests

- Antibodies – answers whether you have already had Covid (and might therefore now be immune)

I still haven’t had either test as yet.

There are suggestions by some that the popular tests produce a lot of false positives.

- When some patients are asymptomatic, tests will always be open to this attack.

Once again, with a vaccine rollout underway, arguments about test accuracy have been superceded.

- The direction of travel is what everybody is looking at – in particular, the government, whose underlying mantra remains “protect the NHS”.

More cases lead to more hospitalizations lead to more ICU demand lead to more deaths.

- Rate of change of positive tests is the best leading indicator we have.

Herd immunity

This idea slowly disappeared as the virus failed to penetrate any community to the necessary levels (in part because of social distancing and lockdowns).

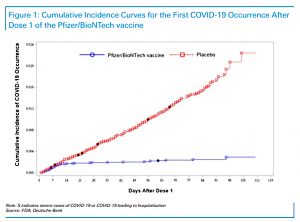

- Of course, deploying the vaccine will lead to herd immunity, assuming that the immune response lasts for more than a few months.

Regular booster shots of a vaccine might be needed, but even a six-month response would give us a good shot at engineered herd immunity.

Vaccine

I’m genuinely impressed by the speed with which several useful vaccines have been developed.

- It’s a coordinated human effort on a par with the space race in the 1960s.

And I expect it to lead to a lot of other medical and healthcare breakthroughs in the coming years.

The rollout brings up a number of issues:

- logistical – some of the vaccines need to be kept very cold, which will be difficult in some countries, and the sheer scale of the programme is unprecedented

- financial – some of the vaccines are expensive, and the cheaper options may be disproportionately donated to poorer countries, regardless of efficacy

- moral – who should be vaccinated first?

I’m happy with the UK prioritisation which favours front-line workers and those most at risk.

- But I’m sure plenty of others will argue for different groups to be favoured.

The potential for the vaccination rollout to take around a year to complete (in the UK) raises the prospect of “immunity passports”.

- Cinemas, pubs and other entertainment venues might be restricted to those who can prove they have had the vaccine.

- As might international flights.

There would logistical issues with this.

- The NHS Test and Trace app is a likely candidate for this purpose, but it isn’t universally popular (though most of the issues are with the follow up).

On the downside, National ID cards have never been popular in the UK (though I can’t see the problem myself).

- It’s hard to see how we can have biosecurity without some loss of privacy.

And such a proposal would further convince the conspiracy theorists and anti-vaxxers that they are right about surveillance chips and mind control.

Lockdown exits

Here in London, we are in “Tier 4”, which amounts to lockdown.

- I can’t leave the Tier 4 area without a good reason, and I can’t stay anywhere overnight.

Christmas Day family gatherings have also been cancelled.

Getting out of this now seems to depend on the vaccine rollout, but it’s not clear how much of the population needs to be vaccinated before the rules can be relaxed.

- I’m in the lowest of the UK priority groups, and according to the vaccine queue calculator (here), I won’t get my doses until May.

And there are 40M people to go after me.

Economic trade-offs

The cost of the lockdown in the UK has risen to £280 bn.

- A lot of this is crowd control rather than real job preservation.

I’m fairly relaxed about businesses going bust since others will spring up to take their place once we have a recovery.

- This is not WW2 when the physical infrastructure was destroyed (and many millions lost their lives).

The worst outcome for me would be that government intervention leads to lots of zombie companies who are too strong to die, but too weak to make significant profits.

Did the lockdown work?

In the narrowest sense of stopping the spread of the virus, lockdowns have not been a great success.

- In terms of avoiding the flooding of the healthcare system, and getting the R number (temporarily) below one, lockdown seems to have worked.

But we don’t know whether these things might have been achieved just more hand-washing, masks and some social distancing.

There is no true counterfactual available since lockdown is the path we chose – the nearest thing we have to a control group is Sweden, the poster-child for “no lockdown”.

- They have significantly more cases per million than the UK, but fewer deaths.

Finding truly comparable countries is difficult since population densities, demographics, healthcare spending and cultural factors (attitude to authority) seem to play such a large role in how the virus plays out.

- Sweden seems to have done a lot worse than its immediate Scandanavian neighbours which used tighter lockdowns.

How has the UK government performed?

This has become a deeply politicised issue.

- To an extent, a pandemic response must be political, since our reactions revolve our attitudes to freedom and to protection.

Statists believe in a “one-size-fits-all” approach, and that the State must know best.

- Strangely, those who believe in big government have been the most critical of our own.

Utilitarians believe in the greatest good for the greatest number, even if this means sacrificing some members of society.

Libertarians like myself believe in individual freedom and personal responsibility above all else.

- People should be encouraged/incentivised to behave well, and more importantly, should not be bailed out when they do not.

I think we won’t know which countries did badly and well for years and that the true measures of success and failure are the macro ones:

- Excess deaths over several years

- Medium-term impact on GDP

The UK didn’t have a good hand, to begin with:

- London is one of the great international travel hubs

- We have a lot of ethnic minority people, who seem to suffer more

- And a lot of overweight people

- And we seem to have bungled the way we handled care homes in the first wave.

Things don’t look great for the UK at this point, but they might look better in a couple of years.

- We appear to have been “unlucky” in the first wave, but other nations are catching up now.

For me, there are five questions to answer:

- Why was lockdown not imposed earlier?

- Why were “bed-blockers” released from hospitals to potentially infect care homes?

- Why the dithering over masks, which might have helped from the start? (( I’m not clear that they do, but in general, all counter-measures should be implemented as quickly as possible ))

- Could the messaging have been clearer? (( It has been confusing to many, though not particularly to me ))

- Was government advice guided by “the science” throughout, or did economic considerations take over for a while, before themselves being abandoned?

On the other hand, we have invented one of the first three vaccines, we were the first country to approve a vaccine (not our own) and we are the first country to start an immunisation programme.

Will the vaccine eradicate the virus?

It’s possible, but the historical track record is not great.

- Smallpox has been eradicated, and polio is almost gone.

But eradication (or anything close) usually takes many years to decades.

- This is a very contagious disease with a foothold in every country in the world, so the omens are not good.

A lot depends on how many people we can convince (or force) to be vaccinated.

- To get to herd immunity we need to vaccinate between 60% and 90% of the population.

- According to opinion polls, the first target should be achievable, but the second will be difficult.

Those who don’t think they are vulnerable (or expect mild or no symptoms) may not be keen.

- Some may want to delay so that any side-effects become apparent, and others may not want to vaccinate at all.

- Or they may want to hold out for a “better” vaccine with a higher effectiveness rate.

And the altruistic motivation of helping others in society is undermined by those most affected – the old and the already ill.

- Many young people appear indifferent to the idea that their elders might die from Covid – or perhaps they genuinely can’t connect the delayed effects of their illegal partying with the cause.

Polio had the “advantage” of striking down young children.

All of which brings us back to the incentive of immunity passports as mentioned above.

- Or even to direct financial incentives.

Conclusions

It might be that we will look back on the lockdowns as a massive overreaction.

- But it’s easy to understand why during the fog of war, the government would prefer to err on the side of caution.

I think we should have restricted travel over the summer, and the schools and universities should have moved to remote teaching only.

- The release of hospital patients back to the care homes at the start of the pandemic also stands out as a big mistake.

Meanwhile hospitality – which in my experience has been pretty safe, and has not been associated with high transmission levels – seems to have been unduly punished because of the optics of drunk people hugging in the street at the kicking-out time.

I would have preferred a true “firebreak” lockdown – with no movement allowed for two or three weeks – over the summer, in order to eliminate the virus.

- Wuhan, the ground zero for the virus, is now back to normal and happily socialising.

Instead, we’ve flip-flopped between tightening and relaxing.

- With many active cases at all times, we run a higher risk of counter-productive mutations like the one we have in the UK at present.

Against all that, we now have a vaccine, and it’s hard to believe that next Xmas will be as difficult as this one.

- More people have died than I expected, but I would have settled for a return to (a new) normal by autumn 2021 – if indeed we get there.

Until next time.