Van Tharp 2 – Objectives and Development

Today’s post is our second visit to Trade Your Way to Financial Freedom by Van Tharp.

Contents

Objectives

Chapter 3 of Van’s book is about setting objectives.

- Objectives are a critical part of any trading system but not many people spend any time on them.

The key objectives are the returns you want to make, the timescale you want to make them, and the drawdowns you are willing to tolerate to get there.

Van also wants to know what rate of return on your capital you need each year for living expenses.

- This is essentially your withdrawal rate in accumulation, and for regular investors, it helps to keep this below 3% pa.

Tom Basso

A large part of the chapter is taken up with an interview with Tom Basso, who we met when he was interviewed by Jack Schwager in his book The New Market Wizards.

Schwager named him “Mr. Serenity,” and he considers [Tom] his best personal role model out of all the market wizards he interviewed.

Some of the topics covered by Tom and Van are:

- the number of hours Tom devotes to trading each day (6 including managing his trading business)

- the need for Tom’s system to cope with distractions

- Tom’s high level of computer skills

- his knowledge of statistics

- and his market understanding

Psychologically, Tom is very strategic and patient, as well as being very self-confident and disciplined.

- He also lacks a compulsive/addictive personality and has no conflicts at work or at home, or emotional issues (fear/anger).

I don’t find trading exciting at all. It’s just a business to me. I look at trading as an interesting brain tease.

Van and Tom move on to objectives, both for the individual trader and for those who manage money.

- I’ll focus on the former (Tom’s replies are in italics).

- What is your edge? Strategic thinking, patience and detachment. Computer programming is also an edge ( long-term automated trend following ).

- How much money do you have? How could you afford to lose? How much risk can you take on a given trade? Several million dollars, 25 percent, between 0.8 to 1.0 percent per trade. However, if I were trading on my own, I’d go to 1 percent to 1.5 percent.

- How much money do you need to make each year? My income comes from my salary at Trendstat. Trading income is simply a second income for me.

- Suppose you have a very good system that is right half the time and gives you profits that are twice as large as your losses. You could still easily have 10 losses in a row. Could you tolerate that? I’ve gone through that in the past, so I know that it is to be expected.

- Do you have the time to trade short term? I have about six hours each day. I don’t plan to trade short term so that’s not a problem.

- How much social contact do you need? Can you work by yourself day after day? I don’t need much. I can easily work by myself.

- What do you expect to make each year as a percentage of your trading capital? About 20 to 40 percent.

- What risk level are you willing to tolerate, and what peak to trough drawdown? About half the potential gain – say maximum drawdown of 25%.

- How will you know your plan is working/not working? I plan everything. I set up worst-case scenarios, and I have specifications on the best case for each scenario. When something comes along, I’ve usually planned.

If the results fall within that range, then I know everything is as planned. If the results fall outside of that range, then I know that something needs to be fixed. Generally, I expect a 40 percent return at the best and a 10 percent return at the worst. I remember one year I had a return greater than 40 percent. What it told me is that our risk was too great.

Trading ideas

Van follows up with questions about markets, entries, exits and money management:

- Tom trades dozens of markets (futures, FX and mutual funds), all of them liquid.

- Entry is the least important aspect of Tom’s system, but he enters when the trend changes, which is the best risk-to-reward point.

- He uses stops in places which contradict the original idea for the trade, rather than as risk control (which is handled by position sizing).

- He has no exit target other than trailing stops.

His answer on position sizing is a little complicated, so here it is in full:

I set up a portfolio of instruments to be traded at set risk and volatility limits as a per cent of equity. I monitor the amount of initial risk and volatility and keep them at set limits.

In addition, I keep the ongoing risk and volatility at fixed percentages of my equity. As a result, I always know how much fluctuation can occur in my portfolio overnight and it’s well within my sleeping limits.

Developing a system

As we discovered last time, Van’s development method is based on modelling successful traders and investors.

Personal Inventory

The first step is to take an inventory of your own strengths and weaknesses.

As we saw in the last section, key items include:

- your computer and maths (statistics) skills

- your starting capital

- your ability to tolerate losses

- the time you can allocate to trading

Van also recommends that you try to answer the question “Who am I?”, and to make sure that your answer aligns with your trading plan.

- The answer should include the type of trading style/timescales you will use, and your target returns.

Market information

Van challenges us to become more open to new ideas and to see that everything we have been taught is a belief.

- And some beliefs are more useful than others.

Once you have an open mind, you can start reading about the markets.

- Van recommends you start with the Schwager books, plus a few others.

When you have read the books, write down your beliefs about the markets.

- Van wants you to come up with at least 100 of them.

These will probably be the basis of your trading system.

- You will only trade a system which fits your beliefs (not Van’s beliefs, or mine).

Concept

We’re now getting into trading ideas. There’s more detail to come on these concepts, but the main options are:

1 – Trend following

- How will I spot a trend?

- How will I know when it’s over?

- Will I trade upside and downside (long and short)?

- What do I do when the market goes sideways (which Van claims is 85% of the time).

- What are my entries and exits?

2 – Band trading – what I might call range or swing trading

- How do define a band?

- When do you enter?

- When do you exit (at or near the upper/lower band)?

3 – Value trading (or rather, investing – this usually takes a while)

- How do I define (and calculate) value?

- When do I buy and sell?

4 – Arbitrage

- There are not usually many opportunities for arbitrage open to private investors, though M&A activity sometimes offers similar situations.

5 – Spreading (FX trading, or pairs trading, also lots of options and futures techniques involving multiple trades)

- This has some elements of arbitrage and others of swing trading.

- There’s usually a long position and an opposing short which should provide a partial hedge.

- Sometimes the long and short are separated in time (expiry date).

6 – Seasonal trades

Big picture

Van has noticed that his clients often gravitate to the hot market, perhaps at the wrong time.

- He recommends using several non-correlated markets (stocks, FX, commodity futures and options) and systems.

Time frame

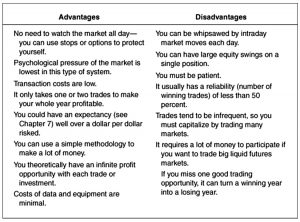

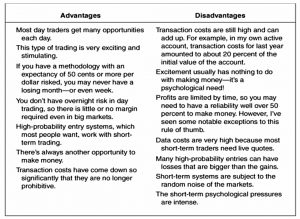

Van has a table showing the advantages and disadvantages of long-term trading.

- For me, the stand-outs are that it is not a full-time job, that there is less psychological pressure, and that you lose less in commissions.

Van sees another advantage:

You have an infinite profit opportunity (theoretically at least) on each position in the market. In many instances wealth builds up because people have bought many stocks and just held on to them. One of the stocks turns out to be a gold mine—turning an investment of a few thousand dollars into millions over a 10-to 20-year period.

The main downside is that you need to be patient and wait for the right opportunities.

- Which means that it won’t suit everyone.

Another problem is that you usually need more capital, to begin with.

- And the best short-term traders should have larger annual percentage returns.

Measurement

Van encourages us to identify the key idea in our thinking, and how it can be measured.

- This should make our criteria for entries clear.

He also recommends testing your signal for profitability on various time periods (after the signal).

- This test should ignore stops and costs.

Van looks for 55% profitability after 1 and 5 days, though I would be inclined to add longer periods (10 and 20 days) since I am likely to focus on end-of-day trading.

R

The next step is to think about stops (which are discussed in detail in a later chapter).

- The main point of the stop is to tell you that your idea isn’t working.

The stop determines what your risk capital is, which is known as R.

- You can then think of potential profits in multiples of R (usually at least 3R).

Expectancy

Van classifies trading systems by the R-multiple distributions of the profits and losses that it generates.

Before we can calculate that, we need to decide on our exit rules (which are discussed in detail in a later chapter).

- Van recommends using three or four different exits in order to maximise expectancy (see below).

Long-term traders like me need to use wider stops.

- We can expect lower win rates, and we need our winners to be as big as possible, which means not getting out too quickly.

Expectancy is the average amount you expect to make on each trade, expressed in terms of R.

- This calculation is discussed in more detail in a later chapter.

Look at your system results trade by trade. What is the makeup of the expectancy? Is it mostly made up of a lot of 1:1 or 2:1 reward-to-risk ratio trades? Or do you find that one or two really big trades make up most of the expectancy? If you don’t have enough contribution from big trades, then you probably need to modify your exits.

Accuracy

Van recommends that we dig into our historical (back-testing) results:

Are your losses 1 R or less, or do you tend to have losses that are bigger than 1 R? What do your profits look like as a function of your initial risk? Do you have some occasional 20 R trades? Or even 30 R trades? Or do you have many 2 R and 3 R gains?

The next step is to trade in small size to see if you obtain the same distribution in practice.

Van says that you should know what to expect across the six different types of market:

- Up quiet

- Up volatile

- Sideways and quiet

- Sideways and volatile

- Down quiet

- Down volatile

Van wants to see 30 complete trades in each market, which probably means more than 250 trades.

- Which could take a while.

Overall evaluation

Van counsels against using win rate to measure a system. Instead, you could try:

- The expectancy of the system.

- The expected gain in terms of R at the end of a fixed time period?

Of course, you need to add some measure of variability to these average returns.

Position sizing

Position sizing is the most important part of any system because it is through position sizing that you will meet your objectives or meet ruin.

Position sizing is covered in detail in a later chapter of the book.

How to improve

Markets tend to change according to the character of the people who are playing them.

Stock markets are now dominated by institutions, and increasingly by the large ETF players (Vanguard, BlackRock and State Street).

Van makes the point that at the time he was writing (2007) the vast majority of fund managers would have only seen one crash – the dot com bubble.

- We’re moving towards a similar situation today, with the 2008 crisis the only one in the last 20 years (apart from the short-lived Covid panic in 2020).

The point is that market research is a continuous process.

Beyond that, extra trades (from extra markets) will usually improve the performance of a system.

- And indeed, using multiple uncorrelated systems will usually improve overall portfolio performance.

This might include a long-term system and a short-term system.

Worst-case scenarios

We already know that Van recommends measuring performance through all possible market types.

- He also recommends preparing for the worst market imaginable.

How would your system perform should the market have a 1-or 2-day price shock against you? Think about how you could tolerate an unexpected, once-in-a-lifetime move in the market, like a 500-point drop in the Dow or another crude oil disaster.

What if we have large inflation again to wipe out our debt? What would happen to your system if currencies were stabilized by linking them to gold? Or what if a meteor lands in the middle of the Atlantic?

Of course, imagining disaster is relatively easy.

- Much more difficult is imagining your response in each situation.

Conclusions

That’s it for today.

- We’re about a quarter of the way through the book now, so I’m still expecting another six articles in this series (plus a summary).

Until next time.