Van Tharp 7 – Stops and Exits

Today’s post is our seventh visit to Trade Your Way to Financial Freedom by Van Tharp.

Contents

Stops

The whole secret to winning in the stock market is to lose the least amount possible when you’re not right – William O’Neil

Chapter 10 of Van’s book is about stops.

The golden rule of trading says to cut your losses short and let your profits run.

We do this by using stops (mental or actual).

Van notes that when things go wrong with systems, investors often blame the entry strategy.

- But usually, if the proper stops had been used, the system would have performed much better.

In my opinion, you do not have a trading system unless you know exactly when you will get out of a market position at the time you enter it.

Which means stops (and exits).

- We’ll come to exits in the next chapter, but short-term traders tend to have a specific exit point in mind before they place the trade, but longer-term traders are more likely to use a trailing stop loss.

Your stop loss determines the maximum loss you are prepared to take.

- This is your initial risk, R.

You may find that your average loss is about half of that, or 0.5 R, depending on your strategy for raising stops. However, sometimes the market will get away from you and your loss will be 2 R or perhaps even 3 R.

If you have an exit in mind, you need to check that is it several multiples of R.

- And don’t forget to include commissions and slippage in your calculations.

[The] R value, if small, will make it possible for you to have very large R-multiple wins. However, small stops also make your chances of losing on a given trade much higher and will cut down on the reliability of your entry technique.

Van has several tips for how to choose the size of your stop:

- assuming that your entry technique is not much better than chance and putting your stop beyond the noise of the market,

- finding the maximum adverse excursion of all your winning trades and using a ratio of that value as your stop,

- having a tight stop that will give you high- R-multiple winners, and/or

- using a stop that makes sense based on your entry concept.

Noise and ATR

The day-to-day activity of the market could be considered noise. If the price moves a point or two, you never know whether it’s because a few market makers were “fishing” for orders or whether there was a lot of activity. And even if there is a lot of activity, you have no idea whether it will continue or not.

So we can act as if the daily activity is noise, and place our stop outside this range.

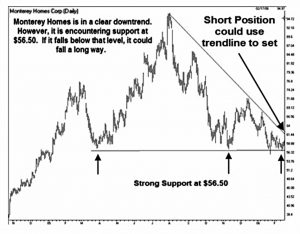

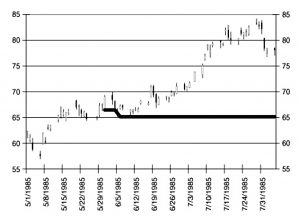

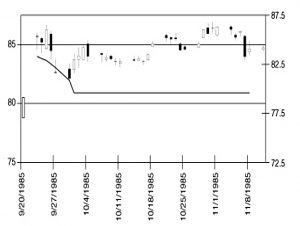

Some people use trend lines, or support and resistance.

One problem with this is that everyone knows where those stops are. You might want to consider putting your protective stop at a level that isn’t “logical” to the market and that is still beyond the noise.

Van suggests using the average true range (ATR):

Now, multiply the 10-day moving average of the average true range by some constant between 2.7 and 3.4 and you’ll have a stop that’s far enough away to be out of the noise.

So let’s call this a 3 ATR stop.

- This was originally designed for the futures markets, and Van suggests that 10 ATR might be a better stop for long-term stock traders.

I’ve never used a stop that wide when actively trading, though it makes sense in the context of my sell rules for my long-term stock portfolios.

- Remember also that wide stops lead to smaller positions since you will have a cap on your maximum loss as a percentage of your portfolio (say 1%).

Maximum Adverse Excursion

The MAE is the worst intraday price movement against your position that you are likely to encounter during the entire trade.

Van points out that MAEs on winning trades are smaller (in terms of R):

Good trades seldom go too far against us.

Which means that we can get away with tighter stops – say 2 ATR.

- He notes however that this analysis is after the fact, and so there is always the danger of curve-fitting.

Van says this should lead to smaller (though more frequent) losses, and a better R ratio (of win multiples to loss multiples

Tight stops

Tight stops lose less money per trade – which is why they are attractive to some – but you will have more losers (lower reliability).

- Because tight stops will also lead to more trades, they also increase your transaction costs.

If you cannot tolerate a lot of small losses, which many traders and investors cannot, then tight stops will be your downfall.

The worst thing a trader can do is miss a major move. Consequently, you must be willing to get right back in the position should it again give you a signal. Many people cannot tolerate three to five losses in a row, which this strategy will regularly produce.

Generally, the 3 ATR stop will be more profitable.

Dollar stops

Dollar stops are hard to guess and are often beyond the MAE.

However, some people confuse such stops with position sizing and then ignore position sizing.

Percentage retracement

Again, this method works much better if the stop is beyond the MAE.

Volatility stops

My experience is that volatility stops are among the best stops you could select.

The 3 ATR stop is a volatility stop.

Dev-Stops

These are stops set one or two standard deviations from a hypothetical normal distribution of prices.

- In fact, prices are right-skewed and have fat tails.

Van explains that a 10% correction is applied to the 1-dev and 20% to the 2-dev to account for this.

- He also suggests using a std dev of the ATR – 1 * ATR + std dev + 10% – or 2*ATR + 2* std dev + 20%

Moving-Average Stops

Van says:

These stops are not nearly as good as stops based on the average true range or MAE.

MA systems produce reversal signals (long to short, or vice versa).

- So you are always in the market and are susceptible to whipsaws.

RC Allen’s 3-MA system is an exception to this rul, as it doesn’t produce reversal signals.

Channel Breakout stops

Channel breakout stops (eg. 20-day low after entry on a 40-day high) are generally too large.

Time stops

The time stop simply takes you out of a position after a fixed amount of time if you haven’t made a profit (or made a profit above some arbitrary level).

Time stops are best for short-term trading.

Don’t use one if you are a long-term trader and have no way to get back in the market should your big expected move suddenly occur. Don’t use one if you have trouble getting back into a position you have exited.

Discretionary and Psychological Stops

Many of the best professional traders use discretionary stops, but I would not recommend them for the amateur or beginning trader. The psychological stop, in contrast, is great for most market players.

There are certain time periods when the most important factor in your trading – you, the human being – is nowhere near 100 percent. These are the times you should just consider getting out of the market.

The times that almost predict certain disaster are (1) when you are going through a divorce or separation, (2) when a significant person in your life dies or is in the hospital, (3) when a child is born, (4) when you move your home or office, (5) when you are psychologically exhausted or burned out, (6) when you are involved in legal proceedings, and (7) when you are [too] excited about the market.

System stops

O’Niel CANSLIM

William O’Neil argues that you should never let a stock go against you by more than 7 to 8 percent.

You would be much better off with a market-based stop. Determine your MAE.

Van suggests once again that you use a 3-ATR stop.

Buffett

Warren Buffett considers most of his holdings to be lifetime holdings. As a result, Warren Buffett doesn’t seem to have any protective stops.

I would strongly recommend that even the most die-hard long-term investor have a worst-case bailout signal. That solution might be as simple as a 25 percent stop.

Kaufman

Kaufman argues that larger stops are generally better because they minimize transaction costs.

He uses a percentage stop as well as reversal signals.

Many of the concepts discussed in this chapter would greatly improve [Kaufman’s] adaptive moving-average system. For example, consider using a volatility stop, an MAE stop, or the dev-stop.

Gallacher

Gallacher enters the market on a 10-day channel breakout when the fundamentals are setups for the market to move in a particular direction. His stop loss is simple. It’s a 10-day channel breakout in the opposite direction.

Once again, Van recommends using his own stop methods instead.

Ken Roberts

Roberts’ setup is a 9-month high or low and then a 1-2-3 pattern. The stop loss is simply putting the stop at a logical point on the chart—just beyond point 1.

Users would be much better off with a stop that was based on a statistical extreme. Several such stops might include (1) three times the ATR, (2) a dev-stop, or (3) [just beyond] an estimate of the MAE.

Taking Profits

People just seem to want to ignore exits—perhaps because they cannot control the market on the exit. [But] exits do control two important variables—whether or not you’ll make a profit and how much profit you will make.

Chapter 11 is about taking profits but begins with an exit that can also be a loss.

The Trailing Stop

Pushing up your 3-ATR stop as the price moves in your favour will reduce your maximum loss, but for a period, the risk of closing at a loss remains.

- Once you are up by your original 3-ATR you can’t lose.

Beware having too tight a trailing stop.

- In this case, moving up your stop could reduce your chances of an eventual profit.

An alternative to a trailing ATR is a trailing dollar amount (which is the way spread bet platforms implement a trailing stop).

Van also discusses channel breakouts, MAs and chart patterns, but I fail to see how these are “trailing”.

- They are just stops, as discussed in the previous chapter.

The Profit Retracement Stop

In order to use a profit retracement stop, you must reach a certain level of profitability such as a 2 R profit.

You might start out at a 30 percent retracement but move the amount down to 25 percent at a 3 R profit and to 20 percent at a 4R profit. You could continue to decrease the amount until you only allow a 5 percent retracement at 7 R, or you might allow it to remain at 20 percent once you reach 4 R.

An alternative is a price retracement stop (like a regular stop loss).

- Van suggests 25%, which is a little wider than I have ever used.

Van discusses lots of other approaches to exits, but I wasn’t attracted to any of them.

- I did see some potential in multiple stops.

For example, alongside the trailing 3-ATR stop, you might also use a daily 2-ATR stop to catch strong adverse moves.

- You might also tighten your trailing stop once a profit target is met (eg. reduce to 1.6 ATR once you get to 4R).

Scaling out

The one exit that Van warns against is scaling out, or “top-slicing”:

This exit produces large losses and small profits. You might start with 300 shares and sell 100 of them when you can break even on all 300 shares. You might then sell another 100 shares at a $500 profit and keep the last 100 shares for a huge profit.

What you are actually doing is practicing the reverse of the golden rule of trading. You are making sure that you will have multiple positions when you take your largest losses. You are also making sure that you only have a minimal-sized position when you make your largest gains.

Common system exits

O’Neil’s CANSLIM

William O’Neil’s fundamental profit-taking rule is to take a 20 percent profit whenever you achieve it. Since his stop loss is about 8 percent, this means a 2.5 R profit.

Sounds good, but:

O’Neil then tempers his basic profit-taking rule with 36 other selling rules. He also adds 8 more rules concerning when to hold onto a stock.

Buffett

Buffett doesn’t sell much, to avoid transaction costs (mainly slippage at his size of trade) and capital gains taxes.

- In those relatively short-term positions where he must have an exit strategy (Van quotes his ownership of 20% of the silver supply in 1998), that strategy has not been made public.

Kaufman

Kaufman’s trend system enters when the adaptive moving average goes up by more than a predetermined filter.

Kaufman comments that one should take profits whenever the efficiency exceeds some predetermined level. He states that a high efficiency ratio cannot be sustained.

Thus, Kaufman has two basic exit signals: (1) when there is a change in the adaptive moving average in the opposite direction, and (2) when the efficiency average hits a very high value such as 0.8.

I think adaptive exits have more potential than any other form of exits. I would strongly suggest that you spend a lot of time in this area in your system development.

Gallacher

Gallacher’s system is a reversal system. It essentially closes out the position (and reenters in the opposite direction) when the 10-day low is breached (that is, a 10-day channel breakout).

However, Gallacher doesn’t use it as a reversal system – [he] takes positions only in the direction of the fundamentals.

This is a very simple exit [and] this system could be improved dramatically with more sophisticated exits.

Ken Roberts

Ken Roberts’ profit-taking approach, in my opinion, is very subjective. It amounts to a consolidation trailing stop approach. Roberts would simply recommend that one raise one’s stop and place it below (or above) a new consolidation once it is formed.

This is an old trend-following approach that worked exceptionally well in the 1970s. Roberts’ methodology would probably work better with many of the exits discussed in this chapter, particularly a multiple-exit strategy.

Conclusions

That’s it for today.

- There are just a few chapters left in the book, and I hope to complete in another two articles (plus a summary).

Stops and exists have been a bit of a slog through lots of options that I can’t see myself using.

- A 3-ATR trailing stop looks fine for me, and kills two birds with one stone.

Until next time.