Warren Buffett’s Annual Letters – 2010

Today we’re going to look at another of Warren Buffett’s Annual Letters, this time covering 2010.

Contents

- Buffett’s Annual Letters

- Performance

- 2011 events

- Five-year performance

- Intrinsic value

- Insurance

- Manufacturing, Service and Retail.

- Regulated, Capital-Intensive Businesses

- Financials

- Investments

- Derivatives

- Reporting: which numbers count

- Black-Scholes

- Leverage

- More quotes from Warren

- Quotes from other people

- Lessons for BH

- Lessons for the Private Investor

Buffett’s Annual Letters

We’ve previously looked at Warren Buffett’s letters that cover 2014, 2013, 2012 and 2011. Today we’ll examine the 2010 letter, which was published in 2011.

I won’t repeat anything that we’ve come across before – there is always a lot of overlap between the letters.

Performance

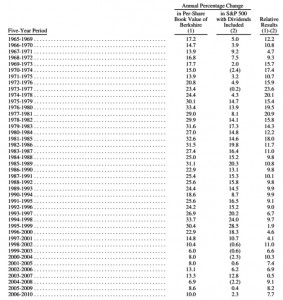

From 1965 to 2010, Berkshire Hathaway (BH) performance was as follows:

- Compounded annual gain:

- in BH book value per share: 20.2%

- in S&P 500 (dividends included): 9.4%

- difference in the two (BH excess gain): 10.8%

- Total gain for the period:

- in BH book value per share: 4,904 times

- in S&P 500 (dividends included): 63 times

Note that the BH share price isn’t being used as a performance measure.

In 2010 the gain for BH was 13%, slightly less than the S&P 500’s 15.1%. No absolute figure (ie. in dollar terms) was provided for the 2011 gain.

2011 events

- Warren describes as the highlight of the year the purchase of Burlington Northern Santa Fe railroad (BNSF).

- This will increase Berkshire’s typical earnings ((Excluding insurance catastrophes and a normal business climate)) by 40% pre-tax and more than 30% after-tax.

- To buy the railroad, 6% of additional shares were issued and $22 bn of cash was used.

- BNSF has a rosy future because of cost and environmental advantages over trucking: rail is three times more fuel-efficient, with reduced greenhouse emissions and a lower requirement for imported oil.

- Massive investment will be needed to grow the railroad as freight traffic increases.

- Normal earning power is now $17 bn pre-tax and $12 bn after-tax.

- BH invested $6 billion on property and equipment, of which 90% was in the United States.

- Lou Simpson, one of BH’s investment managers, retired at the age of 74.

- Todd Combs has been hired as a replacement, with $1 bn to $3 bn under his control and a focus on equities.

- As with Lou, Todd will be paid a salary plus a bonus based on performance relative to the S&P., with deferrals and carry-forwards to smooth out returns.

Five-year performance

Warren measures his success against a target of increasing per-share intrinsic value in BH shares more quickly than the S&P 500 (including dividends). Intrinsic value is subjective, so the conservative proxy of book value is used.

Warren also feels that single-year comparisons can be misleading, and so presented a table of overlapping five-year comparisons with the S&P:

BH has outperformed in each of these 42 five-year periods. The biggest advantage was in the early years (pre-1985) though there were many subsequent good performances in absolute terms, as the wider market did well in the 1980s and 1990s.

From 2000, the market has stalled and BH’s outperformance has led to only moderate gains.

Intrinsic value

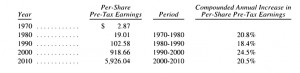

Warren walked us through his calculation of BH’s intrinsic value.

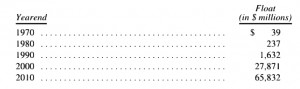

The first item is investments (stocks, bonds and cash equivalents) – these total $158 bn. The insurance float funds $66 bn of these investments, and this is “free” as long as the underwriting operation breaks even over the long term.

The second item is earnings from the non-insurance companies. In the early years of BH, the company focused on investments, but in recent years the focus has been on buying businesses.

As the growth in investments has slowed, the earnings from the non-insurance businesses have grown.

The third, more subjective, element is the effectiveness of how retained earnings are deployed. Warren calls this the “what-will-they-do-with-the-money” factor, as opposed to the “what-do-we-have-now” calculation.

Warren obviously believes they will do well with the money, in part because of BH’s ability to reinvest cash from one business that generates it – but has few opportunities for sensible reinvestment – into another that needs it. (( This conglomerate approach was popular from the 1960s to the 1980s, but BH is almost the only survivor; in recent months it has seemed that Google may be planning to join the conglomerate camp ))

A second advantage is that BH is almost unique in evaluating potential acquisitions against opportunities available in marketable securities. When businesses are priced higher than stocks or bonds, BH buys securities.

A third factor is the BH management team. BH has a hands-off approach and chooses CEOs from a wide variety of backgrounds. Directors receive token compensation: no options, and little cash.

They also do not received liability insurance, so if they mess up, they lose their own money. Apart from Warren, the directors own more than $3 bn of BH shares, which gives them an “owner’s eye”.

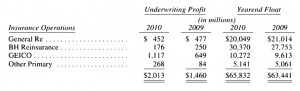

Insurance

The insurance float is now $66 bn.

The insurance businesses have now turned an underwriting profit for eight consecutive years, for a total gain of $17 bn.

Manufacturing, Service and Retail.

Four of the companies in this section had record earnings in 2010:

- TTI, an electronic components distributor

- Forest River, an RV and boat manufacturer

- CTB, a farm-equipment company

- H. H. Brown, a shoe-maker

There was also a major turn-around story at NetJets, which earned $207M in 2010, an improvement of $918M on the losses from 2009. What was BH’s only significant business problem now appears to be solidly profitable.

Ownership of Marmon was increased to 80% from 63%, and will further increase to 100% by 2014.

The home construction businesses have struggled, but Warren expects the housing market to start to recover within a year. Some bolt-on acquisitions have been made in anticipation of this.

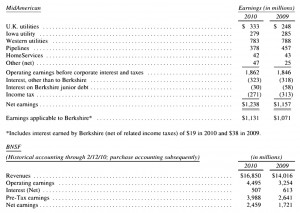

Regulated, Capital-Intensive Businesses

As previously noted, BNSF (a railroad) and Mid American Energy invest heavily in long-life, regulated assets and have large amounts of long-term debt which does not need to be guaranteed by BH.

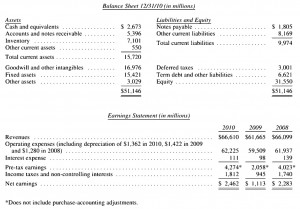

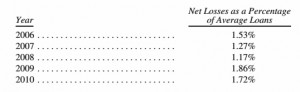

Financials

This is the smallest section of the BH breakdown, and includes rentals of trailers (XTRA) and furniture (CORT) plus Clayton Homes – the US’s largest home builder – and it’s mortgage portfolio.

Warren began this year with an analysis of the mortgage portfolio.

- Clayton has 200,804 mortgages with an average FICO score of 649.

- Forty-seven percent of the borrowers had a score below 640, which is regarded a questionable.

Even so, losses from the portfolio have been small.

Warren attributes this to the borrowers themselves (who borrowed sensible amounts and want to keep their homes) and the fact that Clayton intended to keep the mortgages, rather than securitising them or selling them on. This means that more care was taken in selecting borrowers.

Our country’s social goal should not be to put families into the house of their dreams, but rather to put them into a house they can afford.

There are no financial statements for the financial companies.

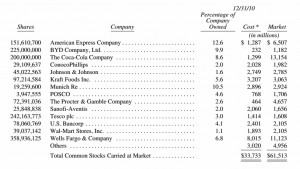

Investments

The table shows investments valued at more than $1 bn.

Derivatives

Warren provided an update on the 251 derivatives contracts from 2008 that BH was involved in. Only 203 remain, in two categories.

Warren compares the contracts to insurance, where BH receives premiums for taking on risks that other don’t want. premiums are received up front, so there is no counterparty risk.

The first category insures against bond defaults by companies in high-yield indices, over a five year period. One hundred companies were covered and $3.4 bn in premiums were received. At the time, BH expected an underwriting profit, and hence the free use of the premiums as float.

With the financial crises, some of the companies failed, and $2.5 bn was paid out. Most of the high-risk contracts have now expired, and it looks like there will be as underwriting profit after all.

The second category is “equity puts”, protecting against falling equity prices in the U.S., U.K., Europe and Japan. $4.8 billion of premiums were received for 47 contracts, mostly lasting 15 years. Only the value of the stock index on the termination date matters.

Eight contracts were closed for a profit of $222M on a float of $647M, leaving 39 contracts which represent $4.2 billion of premiums. At the end of 2010, $3.8 bn would be owed at current index values. Warren expects equity prices to increase and this liability to fall significantly.

Reporting: which numbers count

Warren wanted to point out a number that BH doesn’t use, but the media focus on – net income. Warren says that he and Charlie could legally make that number whatever they liked.

That’s because realized gains and losses on investments go into the net income figure, but unrealized gains losses don’t.

If BH thought that net income was important, they would regularly feed realized gains into the calculation, since they have a huge amount of unrealized gains to draw upon.

Warren considers operating earnings to be a reasonable guide as to how BH’s businesses are performing. Net income should be ignored.

Both realized and unrealized gains and losses are reflected in the book value calculation.

Black-Scholes

Warren doesn’t rate Black-Scholes either. He uses the example of the equity puts. If they had expired on 30th June 2010, the final payment due would have been $6.4 bn.

Stock prices rose in the next quarter, so that the liability reduced to $5.8 bn on September 30th.

But the Black-Scholes formula calculated an increase in the liability (from $8.9 bn to $9.6 bn) – which reduced BH net income by $455M after tax.

Charlie and Warren think Black-Scholes “produces wildly inappropriate values when applied to long-dated options”. That’s why they entered into the equity put contracts. But they have to use the formula for accounting.

The attraction of Black-Scholes is that it produces a precise number, which Warren can’t.

We would rather be approximately right than precisely wrong.

Warren draws a parallel with the efficient market theory, where each fact that refutes it is treated as an “anomaly.”

Leverage

Warren concedes that some people have become very rich through the use of borrowed money, but that really it’s a way to get poor.

It’s addictive, and when the bad times come, it will magnify your losses just as much as it did your gains.

Companies generally assume that debts can be refinanced as they mature. Sometimes, for either general or company specific reasons, they cannot. And then only cash will do.

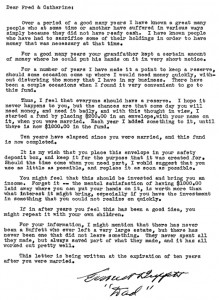

Both Charlie and Warren worked as young boys at Warren’s grandfather’s grocery store, though not at the same time. in 1939, Warren’s grandfather Ernest sent a letter sent in 1939 to his youngest son, Warren’s Uncle Fred.

In 1970, as executor of her estate, Warren found the same letter in his Aunt Alice’s safe deposit box, along with the $1,000 from her father Fred.

Liquidity is important, so much so that BH will always keep $10 bn in cash.

More quotes from Warren

There are just a couple that we haven’t already included above:

To finish first, you must first finish.

A girl in a convertible is worth five in the phone book.

Quotes from other people

You shape your houses and then they shape you. (Winston Churchill)

This is worse than divorce. I’ve lost half my net worth – and I still have my wife. (Investor, 2009)

Economists are most economical with ideas: they make the ones learned in graduate school last a lifetime. (J K Galbraith)

More money has been lost reaching for yield than at the point of a gun. (Ray De Voe)

Lessons for BH

- Liquidity is king – BH will always keep $10bn of cash

Lessons for the Private Investor

- Don’t trust the net income number – book value and operating income are better guides

- Black-Scholes doesn’t work for long-dated options

- Avoid leverage – it will catch you out in time

Until next time.

This post is one of a series on the Warren Buffet Annual Letters. To read the other summaries, go to the Warren Buffet Quotes and Annual Letters page.