Warren Buffett’s Annual Letters – 2008

Today we’re going to look at another of Warren Buffett’s Annual Letters, this time covering 2008.

Contents

Buffett’s Annual Letters

We’ve previously looked at Warren Buffett’s letters that cover 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, 2010 and 2009. Today we’ll examine the 2008 letter, which was published in 2009.

I won’t repeat anything that we’ve come across before – there is always a lot of overlap between the letters.

Performance

From 1965 to 2008, Berkshire Hathaway (BH) performance was as follows:

- Compounded annual gain:

- in BH book value per share: 20.3%

- in S&P 500 (dividends included): 8.9%

- difference in the two (BH excess gain): 11.4%

- Total gain for the period:

- in BH book value per share: 3,623 times

- in S&P 500 (dividends included): 43 times

In 2008 the loss for BH was 9.6%, significantly better than the S&P 500’s 37% fall. The loss in net worth during 2008 was $11.5 bn.

2008 was the worst year for both BH and the S&P 500 in the 44-year history of Warren’s ownership.

Events of 2008

The year was dominated by the credit crunch. Stocks, bonds, real estate and commodities all fell in price.

In God we trust – all others pay cash. (Restaurant sign)

Warren was concerned by the after-effects of the “unthinkable dosages” of economic medicine that was the US Government’s response:

- inflation was a likely long-term effect

- it would be difficult to wean major industries from the public teat

But the medicine was necessary – Wall Street, Main Street “and the various Side Streets” were all in the same boat.

Notwithstanding the problems of 2008, the US had faced worse in the past, and overcome them. The economic system has worked extraordinarily well in unleashing human potential.

America’s best days lie ahead.

Despite the optimism, BH’s businesses suffered this year – particularly retail and housebuilding. The returns from the insurance and utility operations are not so correlated to the general economy.

The silver lining was that capital allocation was easier in a pessimistic market. Three large insurance investments were made on terms not usually available.

But Warren made several investing errors of both commission and omission. More on these later. And the existing investments fell in value with the rest of the market.

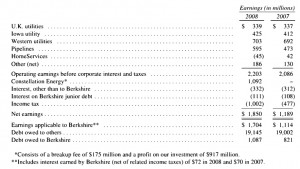

Regulated utility business

This segment of BH performed well, with the exception of a large real-estate brokerage owned by MidAmerican Energy.

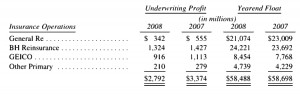

Insurance

Once again there was an underwriting profit, so the $59 bn float of cash cost BH less than nothing.

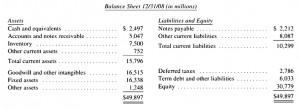

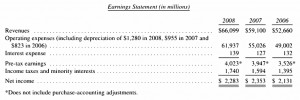

Manufacturing, Service and Retailing

This division earned 17.9% on average tangible net worth in 2008, using only minor leverage. When the goodwill (premium to net worth) is added back, returns fall to 8.1% on carrying value.

That said, earnings in 4Q2008 were bad, and the outlook for 2009 is worse.

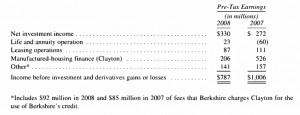

Finance and Financial Products

Warren commented on sales practices in the housing industry, and specifically manufactured homes. Historically (1997-2000), this segment involved:

Borrowers who shouldn’t have borrowed being financed by lenders who shouldn’t have lent.

Salesmen on commission ignored down-payment requirements and signed borrowers up to impossibly high monthly payments. Things ended badly in 2000, and should have served as a warning for the much larger conventional housing market.

Instead the same tactics emerged there, during 2004-07. Borrowers and lenders relied on continuing increases in capital values of houses to make the purchases work.

The delinquency rate for Clayton, BH’s manufactured homes subsidiary was only 3.6%, up from 2.9% in 2006.

This was despite Clayton having borrowers with lower than average credit scores. The reason was that Clayton’s borrowers didn’t borrow more than they could afford to repay.

There were no teaser rates, and no plans to refinance against an appreciating property price, or to sell at a profit if repayments became difficult.

Warren also complained about the advantages of funders with government backing.

Funds for such entities are both abundant and cheap, compared to what is available to BH (at the time, one of only seven AAA-rated corporations in the US).

If this situation is not resolved quickly, Clayton’s future earnings might suffer.

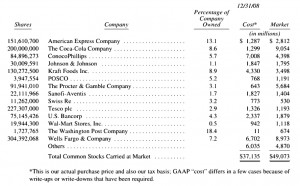

Investments

The table shows investments carried on the BH balance sheet at market value and worth more than $500M.

BH also has 20% holdings in Moody’s and Burlington Northern Santa Fe that must be carried at “equity value” – cost plus retained earnings since purchase, minus the tax that would be paid if those earnings were received by BH as dividends.

The market price of Moody’s and BNSF shares does not affect their valuation in the BH balance sheet.

Warren’s big investment error for the year was buying a lot of Conoco Phillips stock when oil and gas prices were near their peak.

Warren did not anticipate a dramatic fall in energy prices, and still believes that oil should sell far higher in the future than the current $40-$50 per barrel. This mistake has cost BH several billion dollars.

Warren also lost $217M (89%) on two Irish banks.

BH also bought $14.5 bn in high-yield bonds from Wrigley, Goldman Sachs and General Electric. Each comes with substantial equity participation.

Warren feels that risk has gone from being under-priced to over-priced. Good-quality municipal and corporate bonds trade at high yields while risk-free government bonds offer a pittance.

Keeping cash or long-term government bonds is a mistake at present, but holders feel smug for avoiding the recent financial turmoil.

Beware the investment activity that produces applause; the great moves are usually greeted by yawns.

Private Equity

Warren doesn’t like private equity firms.

BH wants to be the “buyer of choice” for businesses, especially family firms. ((In regulated industries, BH hopes to appeal to the regulators who rule on potential acquisitions ))

They do this by:

- avoiding leverage

- giving managers of subsidiaries unusual autonomy

- holding on to acquisitions through thick and thin

The alternative approach is the “leveraged buy out” (LBO) firm. When they gave LBO a bad name, they changed their name to private equity (PE). These firms treat acquisitions as “merchandise” and begin looking for an exit strategy as soon at they have completed a purchase.

In addition, since PE firms usually add masses of debt, diluting the equity, their new name is misleading.

The 2008 credit crisis made this capital structure very risky, but the PE firms did not inject new equity to shore up the balance sheets.

Tax-exempt bond insurance

BH now has a subsidiary called BH Assurance Company (BHAC) which began in 2008 to insure the tax-exempt bonds issued by states, cities and other municipalities, both at the date of issuance (primary market) and later on (secondary market).

This market was attractive because the existing major players (“monolines”) has mostly fallen into trouble. Historically the business was low-risk, but as competition grew and rates fell, they insured ever-riskier bonds.

Early in 2008, BH offered to buy out the books of the three largest monolines for a 1.5% charge. The offer was rejected, which was lucky for BH, as it turned out that Warren had under-priced it.

Subsequently, BHAC wrote $15.6 bn of insurance in the secondary market. Of this, 77% is already insured – mostly by the monolines – and BHAC is liable only if the first insurance company fails. BHAC charged 3.3% for this “second-to-pay” insurance.

Two of the monolines which refused BH’s offer subsequently raised additional capital, ironically making BH’s position on its own policies more secure.

BHAC also wrote $3.7 bn of primary business at 2.6%.

However, Warren is not certain that this insurance will be profitable.

Low premiums for insurance of tax-exempt reflect low default rates of historical bonds, that were mostly uninsured.

Warren refers back to 1975, when New York was on the verge of bankruptcy. It’s bonds were held by local stakeholders, and were uninsured. Eventually, concessions and cooperation led to a solution.

Warren feels that if the bonds had been insured by BH then at best BH would have had to share the burden of any solution, and at worst the bonds would have defaulted.

Warren worries that local governments will face tough problems in the future, largely around pension liabilities. Insured bonds mean that solutions to these problems will be less favourable to bond holders.

The situation reminds Warren of catastrophe insurance. BH will therefore tread carefully.

Warren cautions that such “back-testing” errors are common in all areas of finance.

If merely looking up past financial data would tell you what the future holds, the Forbes 400 would consist of librarians.

He gives as an example the recent losses in mortgage-backed securities.

Here, the loss experience of a period where house prices rose moderately with no speculation was not a good guide to a period of rocketing prices, deteriorating lending practices and unaffordable purchases.

Beware of geeks bearing formulas.

Derivatives

Warren thinks that derivatives are dangerous:

- They have dramatically increased leverage and risk in the financial system.

- They have made it difficult for investors to analyze banks.

- They allowed Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to mis-state their earnings for years.

When BH bought General Re in 1998, they decided to close its book of 23,218 derivatives contracts (with 884 counterparties). This took five years at a cost of $400M.

Warren points out that the Bear Stearns takeover by JP Morgan was brokered by the Fed to avoid a chain-reaction of unknown size.

Warren dislikes the fact that derivatives contracts often don’t settle for years, leading to a huge web of interdependence between financial institutions.

Participants seeking to dodge troubles face the same problem as someone seeking to avoid venereal disease: It’s not just whom you sleep with, but also whom they are sleeping with.

There is actually an incentive for firms to be “too big to fail” – it guarantees a government bailout when things go wrong.

Nevertheless, BH has 251 derivatives contracts. Warren thought these were mispriced at inception, and expects to make a profit.

The contracts also supply an $8.1 bn float to BH, and require little collateral (less than 1% of BH’s investment portfolio).

There are four types of contract:

- $37 bn equity puts – BH pays out if an index – S&P 500, FTSE-100, Euro Stoxx 50, Nikkei 225 – is below the strike value at some point in the future (often 15 or 20 years)

- using Black-Scholes this shows a loss of $10 bn, or a net loss of $5.1 bn after premiums of $4.9 bn

- credit insurance against 100 companies included in high-yield indices

- these were initially 5-year contracts but now have an average life of 2.3 years

- they show a loss of $3 bn in the future; $542M has already been paid out and $3.4 bn in premiums received; the net loss is $100M

- credit-defaults swaps on individual companies, based on the price of their bonds

- $4 bn of contracts have been written against 42 companies

- there are annual premiums of $93M (counterparty risk here)

- no more of these will be written, as collateral is now required

- derivative tax-exempt bond insurance

- a problem here is that mark-to market policies for derivatives are different, and produce strange results

- if these were insurance polices they would show a small profit, but instead they show a $631M loss

- these two results will converge over the life of the derivatives

Black-Scholes

Warren thinks that the Black-Scholes (B-S) formula produces absurd results when applied to long timescales.

He uses the example of a 100-year, $1 bn put option on the S&P 5oo, with strike price 903 (the value at the end of 2008). The B-S value for the premium is $2.5M.

There are a few factors to consider in evaluating this:

- 2% inflation might reduce the value of a dollar to 14¢

- 100 years of retained earning will greatly increase the value of the constituent companies – during the 20th century, the Dow rose by 175 times

The probability of a decline in the index is small, but Warren uses 1%. A serious decline of 50% means the expected loss on the contract is $1 bn * 1% * 50% = $5M.

To cover this loss, the $2.5M premium needs only to be invested at 0.7% pa, compounded annually. This return should be easy to achieve – who wouldn’t borrow money for 100 years at 0.7%?

Even if the worst possible case happened and the entire $1bn was due in 100 years time, the $2.5M could be invested at 6.2% to return this.

Something is wrong here.

The error comes from the use of volatility, and specifically the amount by which prices have moved around in the past.

Warren believes this number has nothing to do with estimating the likely range of values of a business (or in the case of an index, a set of businesses) in the future.

Strictly speaking, the formula is being used to predict a future price, rather than intrinsic value, but the principle is the same.

While historical volatility can be useful in predicting a range of short-term values (and hence in valuing short-term derivatives) it becomes less useful in the long-term.

Warren believes that B-S overstates BH’s liabilities, and that these will diminish as the contracts move closer to maturity.

Quotes

All of the quotes from this week’s report were contextual, and seemed better left where they occurred than moved to the end of the article.

Lessons for BH

- 2008 was the worst year for both BH and the S&P 500 in the 44-year history of Warren’s ownership, but BH still outperformed by 27%.

- BH’s retail and housebuilding businesses suffered, whilst the insurance and utility operations did well.

- Clayton’s future earnings might suffer if the advantages of funders with government backing are not removed.

- Warren made investing errors with Conoco Phillips and two Irish banks.

- $19 bn of tax-exempt bond insurance may not be profitable, since the low premiums involved reflect low historical default rates – this may be a back-testing error.

- By contrast, the BH derivatives contract should be profitable despite currently showing losses; this results from Black-Scholes mispricing of long-dated contracts due to the inclusion of historical volatility in the formula.

Lessons for the Private Investor

- Back-testing errors are common and underlying assumptions must always be checked – are we comparing like with like?

- The Black-Scholes formula doesn’t work for long-dated derivative contracts.

- Derivatives are dangerous, especially contracts that don’t settle quickly.

Until next time.

This post is one of a series on the Warren Buffet Annual Letters. To read the other summaries, go to the Warren Buffet Quotes and Annual Letters page.