Weekly Roundup, 10th December 2014

We begin today’s weekly roundup with a chart from the FT.

Contents

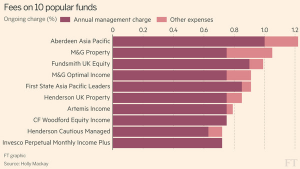

Hidden fund costs

The charges on active funds seem to be in the news every week at the moment. Judith Evans wrote about the difference between the annual management charge (the one that fund managers like to talk about) and the ongoing charge (the real costs that they should be talking about.

The difference between them are a variety of admin costs and bank fees. One notable exception is Neil Woodford’s recent fund, but in other cases they can add up to 0.30% pa. And even the ongoing charge excludes trading commissions and FX charges, which can add yet another 0.6% to 1.3% (not to mention the underlying platform fee for accessing the fund).

For long-term investors like ourselves, these differences matter. The UK Platform group has pledged to switch to the ongoing fee within the year, but what is needed is complete transparency, backed by legislation. Few people would buy a fund that they knew would eat up half of their pension during their lifetime.

Closet trackers

Another topic that won’t go away is closet tracking (unlike the funds themselves). Madison Marriage reported on growing interest across Europe in the practice. In Sweden, 2500 investors have signed up to a class-action lawsuit against a fund manager.

The European Securities and Markets Authority is studying the issue, while regulators in Denmark, and France are also interested. Here in the UK, the FCA said only that it is “the sort of issue [its] new fund supervision team might look at.”

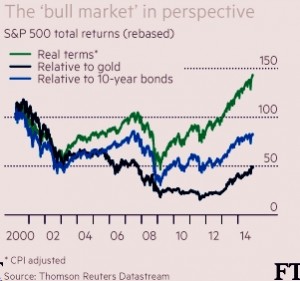

Bull or Bear?

John Authers was trying to decide whether the all-time high in the S&P 500 and 50 months of US job creation means we are in a bull or a bear market. He pointed out that since the dot-com peak of 2000, the S&P lags both gold and bonds (though it beats inflation even from that unflattering start line.

John subscribes to a definition of secular market cycles driven by stock valuations (specifically the 10-year cyclically-adjusted p/e popularised by Robert Schiller of Yale). The last great low (below 10) was in 1981 – 2009 didn’t quite make it. Therefore a new bull market can’t have started in 2009, and this is a bull rally in a bear market.

The CAPE now stands at 26.5, higher than ever outside of 1929 and 2000. To get below 10, we need a 160% increase in stock earnings, a 60% price crash, or a combination of the two. Even to a pessimist this seems unlikely, but John feels that we need to get past low interest rates and money printing before we can be sure.

I appreciate the historical perspective, and feel that the US is over-priced relative to Europe and Japan (and even the UK), but this feels like semantics to me. There is a US bull market, but for how much longer? If 2009 really was the bottom, maybe for several more years.

Complex income products

Judith Evans also reported on opposition from the CEO of Aviva to regulators’ plans to restrict access to complex products to sophisticated investors, or to restrict sales to via IFAs only. Euan Munro was responsible for introducing Global Absolute Return Strategies (GARS, growth) funds at Standard Life, and has since set up similar income funds (Aims Target Income) at Aviva.

His argument is that in the current low-interest-rate low-return climate, the 4%+ yields needed by pension investors are not available without the use of leverage and derivatives (swaps and futures). I agree, but that does not necessarily mean that the funds should be available to everyone. Since anyone with a £250K portfolio can self-certify as high-net worth, restricting access to HNWIs might seem to be an appropriate compromise.

This still leaves the problem of what a pension with less than £250K should invest in. Diversified equity income would seem the obvious choice, supplemented by the government’s long-awaited Pensioner Bonds. Sadly it seems that the latter will be limited to £10K per pensioner, and £10bn in total (meaning they will likely sell out quickly, and will act as no more than a sticking plaster). It would help a little if the tax-sheltering of P2P loans could be accelerated.

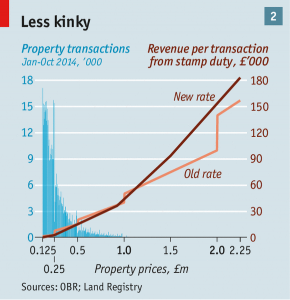

Stamp duty reform

John McDermott confirmed that the impact of changes announced in the Autumn Statement will fall on London: 70% of recent £1M+ sales were in the capital. He also explained why the changes will not benefit buyers, as widely reported.

At the tax reduces, the number of transactions (the demand) rises. In an illiquid market like property, with relatively fixed supply, this means a rise in prices. The reduction in tax will also increase deposits, which may in turn increase mortgage sizes.

So for most people prices will rise: the OBR estimates that for every 1% fall in stamp duty, they rise by 1.4%. A study of what happened when duty was cut in 2008 found a 20% increase in activity, and a long-term increase in prices.

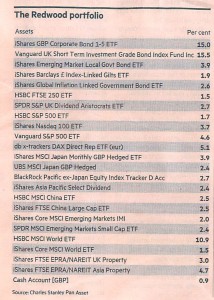

Redwood ETF portfolio

John Redwood gave his regular update on the ETF portfolio he runs. The bulk of his column was focused on the impact around the globe of the falling oil price. I will return to this in a post on oil in the next week or so, but for now here is the latest portfolio.

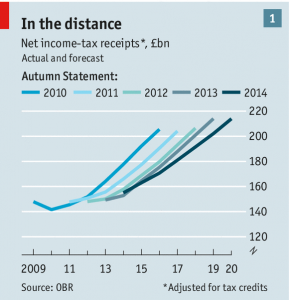

Autumn Statement

The Economist commented on the lack of pre-election goodies in the Autumn Statement. This is largely down to disappointing tax receipts from a low-wage recovery on the back of tax cuts for low earners. There is presently no obvious reason for this situation to change.

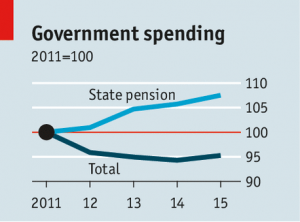

The second reason is that a future Conservative government would need to make further cuts. With government’s share of GDP set to fall from 41% to 35% – and with health, education and aid ring-fenced – other departments must shrink by £61bn (40%).

Means-tested pensions

In a leader published before the Statement, the newspaper advised the government to means-test the state pension, removing it from households with income over £65,000.

Whilst the fiscal logic of this is clear (demographics and the triple lock of pension increases mean that pensions consume more of public spending) the morality is murky. Pensioners retiring today may have been in the workforce for 50 years, contributing via NI to fund their pensions (as they understood it).

That the NI pot is not in fact separate from general spending doesn’t invalidate these contributions. Removing a £12K pension from a couple on £65K pa is quite a kick in the teeth.

Phasing out pensions for the “rich” would take years to implement, would be politically difficult and will surely not be achieved through the introduction of a “slab” system so soon after another unpopular slab (Land Stamp Duty) has been removed.

High-frequency trading

The Economist also took a look at High Frequency Trading (HFT), the subject of criticism earlier this year in Flash Boys, a book by Michael Lewis.

You can buy the book here: ((this is an affiliate link, and I will be paid a small referral commission if you buy through this link))

[amazon text=Amazon&asin=0241003636&text=Flash Boys&template=thumbnail]

FlashBoys

Flash Boys criticised HFT firms for front-running (getting in ahead of large, market-moving orders and slicing off a bit of the price). Regulators have been debating whether to introduce deliberate delays, or to shuffle trades (effectively, use random delays).

HFT defenders claim that the practice improves liquidity, citing a reduction in typical bid-ask spreads as HFT has become more popular (it now accounts for 50% of US stock trading). But this could simply be down to increased computing power, and a recent study has demonstrated that HFT will reduce the size of trades that market-makers will undertake.

This is because the risk associated with each trade has increased as the HFT firms shrink the market-makers’ margin of safety (the spread). In turn, this means that the originators of large orders will see their costs increase as the market moves further against them.

The market-makers have adopted HFT techniques themselves, but neither side can maintain a lead in this technological arms race. The proposed solution is to divide the day into a series of mini-auctions (lasting perhaps just a second) where bid speed is ignored.

This is fascinating stuff, but of little practical use to the long-term private investor. Shaving micro-pennies off a pair of trades (buy & sell) placed months or even years apart will have little effect on the annualised return. It may be that as in FX, these effects have a tendency to cancel out towards zero over time.

American pensions

Buttonwood looked at a new book on the looming US pensions crisis. Americans live longer but retire earlier than they used to. Their pensions (private and governmental) are down and their medical expenses are up. Falling Short explains the three options: live less, work more or save more.

You can buy the book here: ((this is an affiliate link, and I will be paid a small referral commission if you buy through this link))

[amazon text=Amazon&asin=0190218894&text=Falling Short&template=thumbnail]

Falling Short

Most people in the US receive a government pension, but the Social Security fund has been leaking money to early retirees for years, and will run out of money in 2033. To counter this, the retirement age is being raised to 67, and the “replacement” (payout) ratio is being reduced from its historic 40% of salary for younger retirees. Higher deductions for Medicare are also in plan, and the payout ratio will hit 31% by 2030.

As in the UK, private sector defined benefit plans have been replaced by defined contribution (401k) schemes with low (9% annual) contributions. Median pension pots are now lower than projected medical expenses. Reverse mortgages (home equity release) will be needed by many.

There are no easy solutions here, on either side of the pond.

Franklin Templeton bond fund

The Economist also had an article on the Franklin Templeton bond fund, run by Michael Hasenstab, philosophical heir to Sir John Templeton. In personality terms he is unlike Bill Gross, but his fund is just as impressive, returning 8% annually over the last ten years.

Hasenstab specialises in large contrarian bets, lately Ukrainian debt. He is also the largest bond investor in Ghana, Ireland, Hungary, Iraq, the Philippines, Sri Lanka and Uruguay. His argument is that with interest rates about to rise after a 30-year bull market in bonds, he needs to find mis-priced countries.

Some of his critics say that he is just front-running IMF bailouts, others that he props up nasty regimes. He has certainly avoided bailout countries (eg. Greece) and invested in others where the IMF was not involved.

It’s an interesting fund, and diversification from the typical bond fund. Whether it sounds too good to be true I leave to your own judgement.

2 Responses

[…] section of the Economist carried no fewer than four angry responses to the extremist proposal from last week that high income pensioners should not receive the state pension. The letters focused on the […]

[…] Economist has previous on attacking pensioners, as do I on defending them […]