Weekly Roundup, 13th February 2023

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup with land tax.

Land Value Tax

In the FT, Martin Wolf was arguing in favour of a land value tax.

- It seems to be open season on ideas for new taxes in the UK at the moment, presumably because the Sunak government has its first real Budget next month, and further out most people expect a Labour government to implement its own tax regime in 2025.

I’m sure that most people agree that the tax code shouldn’t remain static, but most of the articles I read are coy about the impacts of their proposals.

There are five things I want to know in order to evaluate a new tax:

- Which taxes are the new tax meant to replace?

- Is it designed to raise more money or less than the existing ones?

- Given the relentless climb in government spending, and the huge government debts run up during Covid, the answer will usually be more.

- Who are the winners and losers from the change, and how much will they win/lose (both annually and cumulatively)?

- There should be (but usually isn’t) some kind of moral argument here as to why the winners deserve to be richer and the losers don’t deserve the money they already have.

- Will it be implemented as a cliff edge, or will there be a transition period?

- And will existing users of the old system be grandfathered in (allowed to keep what they already have)?

- What behavioural response is expected from the changed incentive structure that the new tax creates, and to what extent does that new behaviour undermine the perceived advantages of the change (for example the extra tax raised)?

Let’s see how Martin gets on.

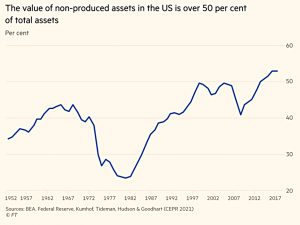

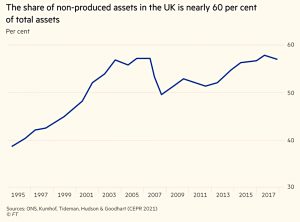

It’s not a great start, with Martin discussing a lot of dead economists and focusing on the distinction between non-produced capital (land) and produced capital.

- He thinks that bundling the two together (in neo-classical economics) is a big deal.

As a result, taxes on land were increasingly considered in the context of taxes on wealth, even though natural resources are quite different from the capital stock created out of effort and foregone consumption.

Speaking as an investor, this feels spurious.

- The investment process starts with creating an annual surplus (by consuming less than your income).

This foregone consumption can then be invested in (ideally) a wide mix of assets, with a view to creating an asset base large enough to live on (financial independence).

There are three relevant points of detail:

- The income that creates the asset base has already been taxed, and there is no moral case to tax the growth of that asset base.

- In the UK, growth in ISAs is sheltered, and growth in pensions is taxed on a deferred basis with the first 25% exempted.

- The asset base will include land/property and there should be some tax shelter available to protect that element.

- In the UK, capital gains on your primary property are not taxed, and annual property taxes are of the order of 0.1% pa (a bit higher for cheaper properties).

- Financial independence means that no further direct effort is required – the indirect effort of managing your asset base is sufficient to provide a living.

- I see no moral case that working in an office or shop is more deserving than managing your own portfolio.

Martin would argue that, for example, the growth in the value of my London home is down to the local infrastructure, to which I did not directly contribute. I would say that:

- The growth is often exaggerated and does not compare well with that of stocks

- Forecasting which area will exhibit rising property prices is part of the investment process

You can certainly argue that property is expensive and too much capital is tied up in it, but you can say the same thing about any expensive asset (cars, jewellery, art etc.)

- The money goes to things that people with money want the most – as it should.

The reason that people want to tax property more, and bring its price down, is that everyone needs a house, in the same way that everyone doesn’t need a Monet or a Ferrari.

- But that doesn’t make it right – and getting from here to there could be horrific.

The implementation that Martin favours is from the Centre for Economic Policy Research, as summarised here.

- They propose a 5% increase in land tax introduced over 20 years – that’s an increase of about what I pay at the moment every year (possibly for the rest of my life).

Five per cent pa on my London home would be unpayable by almost everyone, and property values could be expected to tank as soon as the transition was announced – with potentially catastrophic consequences for the UK economy.

- What happens to the mortgage market, or the rental market if capital values fall by 50% and rentals double overnight?

Even if 50% of the property value were assigned to the land (and the remainder to the building), the resulting taxes would have the same effect.

- Martin proposes imposing the new tax only on land values higher than those of today, but the effects would be the same if perhaps a little slower to surface.

If any political party proposes a land tax of more than say, 0.3% pa, (( I plucked this out of the air as a reasonable annual cost to pay on an investment portfolio )) it will be time to run for the hills.

Growth

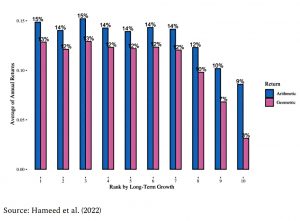

Joachim Klement looked at growth stocks, and in particular long-term earnings forecasts.

A lot of shenanigans can be justified by assuming high long-term earnings growth. But when that earnings growth doesn’t materialise, share prices can come down a long way even though the immediate outlook for next years earnings remains the same.

A recent study looked at US stock returns from 1981 to 2018.

- Higher long-term growth assumptions lead to underperformance, particularly in geometric returns (which are the ones that matter).

Luckily (for new investors) stock price falls in 2022 have brought down a lot of the most egregious earnings estimates.

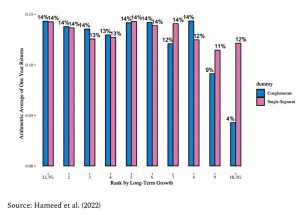

Conglomerates were particularly susceptible to this earnings effect.

Joachim explains this in terms of conglomerates exploiting differences between their subsidiaries:

While different segments of a conglomerate have different cycles and thus different revenue growth over time, management can smooth earnings for each division by allocating costs away from underperforming segments and towards high-performing segments.

This creates the illusion of a steadily growing, stable business.

- Which leads to them becoming overvalued and eventually underperforming.

If I look through the S&P 500 these days, I can find among the top 20% companies with highest long-term earnings growth such conglomerates as General Electric, Danaher, and Disney.

Beware.

State pension age

In FT Adviser, Ros Altmann came out against further increases in the state pension age.

- It’s not so much the principle of a rise, as its impact on “disadvantaged” groups.

Even those with seriously shortened life expectancy and up to 50 years contributions to national insurance, cannot receive a penny of state pension early. Just raising the state pension age because ‘average’ life expectancy has increased is a blunt cost-cutting ‘social welfare’ tool which is not suitable for UK society.

Poor people tend to die younger and remain in good health for a shorter period of time.

- The poorest 10% have good health at 52, whereas the richest 10% have good health at 70.

The state pension has already been increased from 65 (for men) to 66 and will rise further to 67 before I am old enough to receive it.

- A review will report in May which could bring forward further rises to 68 and beyond.

The theory is that the average person should spend one-third of their adult life (post-18) in retirement.

- There’s also another unwritten rule that potential retirees get ten years’ notice of changes (though this was broken when the minimum age for SIPP withdrawals was raised from 50 to 55).

I think Ros is missing the point of the state pension (or perhaps I am).

- It’s income for when you reach a government-decided age when you are no longer required to work, to help support you for the rest of your life (however long that might be).

It’s not support for ill health or bad luck in the longevity genetics lottery.

By definition, insurance schemes have winners and losers.

- When it comes to pensions, the losers are those who die young, and the winners are those who live a long time.

Schwab

Charles Schwab has reduced the minimum balance on its US stock trading accounts to zero (from £$25K previously).

- Trading of US stocks is zero-commission part from an initial FX fee.

The timing is good, as one of the existing free brokers (Australian outfit Stake) just added a $3 transaction fee.

Schwab also offers options trading, which requires further investigation at some point.

- But unlike Stake, there’s no access to US-listed ETFs.

Schwab UK MD Richard Flynn said:

Our new $0 minimum investment opens up our services to all investors. The transaction volume, market capitalisation, and number of listed companies make the US market a unique and attractive option for international investors.

Our new services are designed to help UK retail investors expand their investment

options in the US market. We believe our platform provides investors with one of the most affordable and insightful ways to invest in American businesses.

Quick Links

I have four for you this week:

- The Economist looked at The battle for internet search

- And wondered Is Google’s 20-year dominance of search in peril?

- UK Dividend Stocks gave us their S&P 500 CAPE Valuation and Forecast for 2023

- And Alpha Architect looked at Factor Returns and the Information in Valuation Spreads

Until next time.

Re: “If any political party proposes a land tax of more than say, 0.3% pa,1 it will be time to run for the hills.”

I assume you are referring to annual council tax as a percentage of property vale. In which case, is there maybe a hint of some London bias in your figure?

There’s generally a lot of London bias in what I write, but [as the footnote explains] in this case, I’m just quoting what I see as a reasonable annual charge on an asset. Unless there’s a good reason (eg. the tax breaks on VCTs, or some diversifying assets) you should think about getting out of things that are more expensive than that.

IIRC, the ‘ten year rule’ only applies to changes in the state pension age

I’m sure you’re right, but morally we should expect plenty of notice of changes to any retirement rules.