Weekly Roundup, 27th September 2021

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup with a look at bubbles.

Bubbles

In the FT, Robin Harding looked at how to decide when a market is in a bubble.

- He began with The Big Short, suggesting that some of the US housing market’s rise was actually driven by fundamentals.

He quotes a study – by Gabriel Chodorow-Reich, Adam Guren and Timothy McQuade –

that offers as evidence the fact that house prices have recovered to reach new highs.

- The Case-Shiller index peaked at 184.6 in 2006 but now stands at 260.9.

Chodorow-Reich says:

It’s not just a boom-bust-rebound in national data but also in local data. Those places that had the biggest booms had the biggest busts and the biggest rebounds.

This cycle is correlated to supply and demand factors like land availability, zoning rules, wages, weather and the number of local restaurants.

- But why does the boom lead to a rebound?

Chodorow-Reich says that over-optimism (during the boom) and leverage are factors.

Some of what changes is the industries that are taking off. It’s around the time that tech is becoming very important. The start of the national boom is also coincident with the decline in crime in the US, which made central cities much more attractive again.

Since housing supply can’t respond quickly prices boom, then bust.

- Neither subprime credit nor speculative investors are necessary.

Robert Schiller has also noted that bubbles do not burst irrevocably:

Though the abrupt ends of stock market booms in 1929, 2000 and 2007 might seem consonant with such a metaphor, these booms were reflated again before long, [in] 1933-37, 2003-2007, and 2009-present respectively.

Today’s most likely bubble is big US tech – but is it really a bubble?

For the 2008 housing crisis, the answer seems to boil down to:

- whether you define a bubble as a period when prices are well above (often defined as two standard deviations above) fair value,

- or whether these prices arise from real changes in fundamentals which will lead (via a boom and bust) to high prices in the longer term.

As for tech, the same model fits the previous boom and bust, in 2000:

Valuations then were about as extreme as the stock market has ever seen, but it is hard, in retrospect, to say that investors were wrong about the importance of the internet or the profits to be earned from moving business online. They were simply too early and had the wrong set of companies.

The best candidate for a fundamental driver of tech valuations in the current boom is the long-term decline in interest rates.

Ben Inker, head of asset allocation at GMO, said:

Prices in the US equity market look extreme relative to history, but they look less extreme relative to interest rates.But it’s still very explicitly a bet on where real interest rates are going to be or that they’re going to continue to go lower.

Shiller also thinks that there are explanations available.

- the stock market is expensive relative to historic stock prices but reasonably priced in comparison to bond yields.

Economist Andrew Smithers says that interest rates don’t matter:

You can demonstrate overvaluation without reference to the level of interest rates.

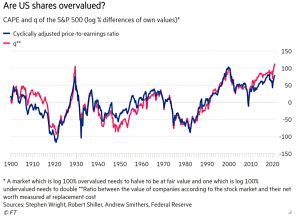

He likes the Shiller CAPE (which has a poor track-record over the short term, but is not bad over longer periods of ten years or more) and Tobin’s Q, which compares the market value of corporate assets to their replacement cost.

- Both measures are close to the 1929 and 2000 highs.

The fact that we are still debating the US housing bubble 15 years after it began doesn’t bode well for the true challenge of investing – spotting bubbles in real-time, or even better, in advance.

Housing

In The Times, Ian Mulheirn (who works for Tony Blair’s think-tank) said that the UK’s housing problem was not just down to how few houses we build.

- The article comes in the wake of speculation that the proposed relaxation of planning laws is set to be shelved following a Tory by-election loss in which the NIMBY vote switched to the Lib Dems.

Proponents argue that a radical overhaul of the present system could boost housing supply, cut prices and thereby revive anaemic rates of home ownership, [But] the approach would have had no impact on home ownership and little effect on affordability.

According to Ian, each year of the last decade has seen 100K more planning permissions granted than homes built.

- A lot of these are in London, where the housing shortage is apparently the greatest.

Ian estimates that hitting the government target of 300K houses per year would take a decade to reduce prices by 10%.

- Meanwhile, prices have gone up by that much in the last year. (( Not where I live, unfortunately – prices are falling here ))

And these price rises are against a surplus of houses relative to households which rises each year and has doubled over the last 25 years.

For Ian, the key driver of house prices – high deposits notwithstanding – is the availability of credit, particularly for first-time buyers.

- These are risky borrowers, and lenders avoid them when times are tough.

So when houses are cheaper, first-time buyers are locked out.

Ian wants the government to help, but when it does (as with Help to Buy), then prices just move even higher.

- His other suggestion is to make renting better for tenants, but structural intervention in the rental market just leads to a smaller market of lower-quality properties.

Or perhaps Ian means that we should build more council houses.

Private Equity

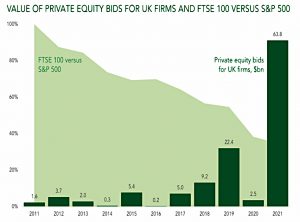

Steve Russell at Ruffer wrote about the increase in PE bids for UK companies, now that UK stocks have fallen so far behind US valuations.

Over the last decade the UK stock market has underperformed the US by over 60% and now trades on a forward price-to-earnings ratio (PE) of just 13x compared to 21x for the S&P 500.

Brexit, a bad start to handling Covid and a lack of large tech firms were some of the reasons for the UK falling behind, but takeover volumes are now running at twice the level of the US or Europe.

So far there have been bids for John Laing, Ultra Electronics, G4S, McCarthy & Stone and Aggreko amongst others, plus of course Morrisons. What do all these companies have in common? They were too cheap for the kind of reliable free cashflows they offer bidders with access to vast amounts of money at ultra-low interest rates.

FIRE

The FT had an interview with Pete Adeney, better known as Mr Money Mustache.

- Probably his most famous article is “The Simple Maths Behind Early Retirement”.

Pete’s insight was that the more of your income that you save, the quicker you build up the pot to fund the money you spend from your savings.

- Pete retired in his thirties.

Spending is the part that’s within our control and it’s something you can change -starting today. Start tracking your spending and figure out where the money is going. Getting more conscious about your spending choices means you can keep a lot more of the money for yourself and invest it.

He advocates saving a very large proportion of income – 50% or more.

Traditionally they teach us to save like five or 10 or maybe 15 per cent of our income, and that does work, but that’s what gets you to a retirement age of around 65 years old. That was depressing to me because I’m still far from 65 and, oh my goodness, I can’t believe how much I am glad not to be in an office job even now at 46 years old.

Pete uses a 4% withdrawal rate, which means the pot needs to be 25 times your spending.

If you have like 20,000 annual spending, whether it’s pounds or dollars, multiply that by 25 and that’s 500,000 that you’d need in investments, very roughly. And if you have a 40,000 spending rate then you’d need a million invested.

I prefer a 3% SWR, which means a pot of 33x.

Cash

In the FT, Joshua Oliver reported that the FCA has launched an £11M marketing campaign to discourage savers from hoarding cash.

- There are 8.6M Britons with more than £10K in cash, and the FCA plans to persuade 20% of them to switch.

Sarah Pritchard, the FCA’s executive director of markets, said:

We want people to have greater confidence to invest. We also want to be able to adapt more rapidly to the changing market and be assertive where we see poor conduct and consumer harm.

Many consumers who might gain from investing currently hold their savings in cash. Over time, these consumers are at risk of having the purchasing power of their money eroded by inflation.

That much is true, though I’m not certain that £10K of cash is the level where people need to worry.

- For many, that would be less than six months’ expenses.

We need to educate people about two things simultaneously:

- They need to save 20% of everything they earn

- They need to invest this in a diversified portfolio of mostly stocks, rather than a cash savings account

Inflation

Buttonwood wondered whether physical assets would provide protection from inflation.

- He worried that property, infrastructure and farmland could prove victims of their own success.

Inflation often coincides with rises in the prices of these assets. An economic expansion tends to fuel consumer-price growth as well as demand for floor space and transport or energy infrastructure. Moreover, these assets produce cash flows that usually track inflation.

Historically, such assets outperform stocks and bonds when inflation is above 2.5% pa.

- Buttonwood is worried, though:

Performance has become harder to predict: think of retail space and office blocks (under threat from e-commerce and remote work), airports and power plants (exposed to decarbonisation) and even farmland (vulnerable to climate change).

There are also access and liquidity issues.

- Primary assets are generally only available to wealthy/sophisticated investors, and the funds that offer indirect access are more closely correlated to equities.

And there is potentially a bubble forming:

Between 2010 and 2020 private real assets under management more than doubled, to $1.8trn. Finding things to buy is getting harder.

Quick Links

I have six for you this week, the first five from The Economist:

- The newspaper looked at the systemic risks of an Evergrande collapse

- And noted that natural gas prices are spiking around the world

- The Economist also wrote about a UK takeover which shows that shareholders still run companies

- And said that fiscal rules can help, despite the US debt ceiling disaster

- And warned of a backlash as financiers move in on rental properties.

- Alpha Architect looked at crowding and factor premiums.

Until next time.