Weekly Roundup, 23rd June 2015

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup with John Authers in the FT.

Contents

Market complacency

John was worried about market complacency in the face of Grexit and the Fed raising interest rates.

Markets appear to be pricing in a deal on Greece, or are convinced that Grexit would have little impact. John agrees that the former is likely ((It looks even more likely as I write this)) but is not so convinced of the second.

There are two possible issues – contagion from the Greek default itself and the precedent set by a country leaving what was envisaged as a permanent currency union.

I think the risk of the first is low – Greece is a small country and the EU has had seven years since the collapse of Lehmans to tidy up the debt – but the second is an unknown quantity. If Spain or Italy decided to leave, all bets are off.

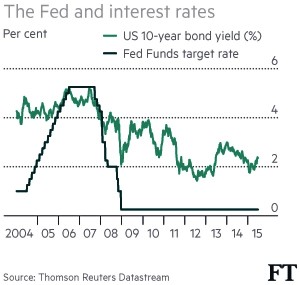

As for the Fed, their June meeting had long been seen as the first one at which base rates might be raised. Of course it did not happen, following a first quarter slowdown in the US.

Janet Yellen said that rates will start to rise between September and March, and that the rise would be gradual. The futures markets have ruled September out, and think December or January is more likely.

There are four risks associated with the rate rises, whenever they begin:

- money returns to the US from foreign markets, as per the “taper tantrum” in 2013

- money is attracted to the US by rising rates, pushing up the dollar, making things difficult for US exporters

- rising rates (even gradually rising ones) create a new recession, as per the Depression in 1937

- long-term interest rates don’t react, and remain low (10-yr rates are 2.5%), making credit attractive and another credit bubble possible

So plenty for the markets to worry about, if they wanted to.

P2P goes business

Judith Evans noted that P2P lending to business is about to surpass that to individuals.

The higher rates on offer (6% upwards, compared to around 5% for consumer loans) appear to be outweighing the increased risk on the loans.

Lending to consumers totalled 1.583bn as at the middle of June, with the faster-growing lending to SMEs just behind at £1.581bn. Property-backed lending to businesses has now passed £600M.

The growth has been reflected in the number of platforms – there are now 16 business platforms in the AltFi index, compare to only five dealing with loans to consumers.

The rapid growth is partly driven by institutional lenders joining the party. They have more to lend and the larger deal sizes with business are attractive. It’s also the case that since the financial crisis, bank lending to SMEs has shrunk.

Private Wealth Management

The FT also published its Private Client Wealth Management supplement.

The first point to note was that the price of entry has gone up by 50% since last year. Higher compliance costs mean that firms are avoiding less profitable clients.

The FT’s 2015 survey found that the average minimum amount of liquid assets need to access advisory services is £806K, a 48% increase from last year’s £542K. For discretionary services, £650K was needed, a 27% increase on £517K.

Not surprisingly, client satisfaction fell from 62% to 54%. There is some hope for improvement however:

- client to staff ratios fell from 175:1 to 161:1

- annual fees on portfolios over £1M fell by 5 basis points (0.05%)

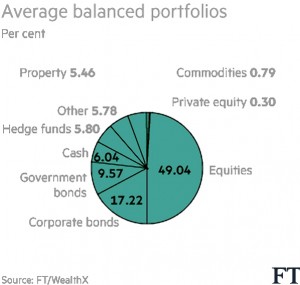

The second finding was that wealth managers have been pushed up the risk spectrum in search of alpha. Even so, over the past three years, less that 20% of managers added alpha, whereas more than 50% generated negative alpha.

Equity allocations are at record highs. This partly reflects the equalisation of bond and equity volatility under QE. Corporate bond allocations have fallen, with short-dated government bons (included index-liked ones) now preferred.

Alternative asset classes like hedge funds and private equity are up slightly. Many managers are also adding P2P debt through investment trusts. Property and infrastructure are less favoured as property yields fall and infrastructure trusts’ premia to NAV increase.

A third finding was the (slow) advance of “robo-advisers” or online discretionary services.

The biggest names in the UK are Nutmeg and Money on Toast, but their reluctance to reveal their level of assets under management suggests that progress has been slow.

Hargreaves Lansdown, the biggest direct-to-consumer platform launched its Portfolio+ service this month (we compared it to Nutmeg last week). ((We didn’t include Money on Toast in the comparison, but MoT seems to be an even more expensive option than Nutmeg, with annual fees of 1.49%))

Investec, Brewin Dolphin and Barclays each plan similar launches this year.

In the US, the leading online services (Betterment and WealthFront) both use passive portfolios of ETFs. This is the Nutmeg approach, but Hargreaves Lansdown and Fidelity both offer portfolios of mutual funds.

The O-ring theory

Life, and in particular, science and technology, is getting more complicated. Ben Jones has found that researchers and inventors are getting older and have narrower specialisations. As the body of knowledge increases, it takes longer to master what is already known before you can add to it.

Tim Harford looked at Why Information Grows, a new book by César Hidalgo, a physicist at MIT.

[amazon text=Amazon&asin=0241003555&text=Why Information Grows&template=thumbnail]

Hidalgo uses the term “personbyte” to describe the amount of knowledge that one person can know. More and more of the personbyte is being filled up with what we already know. The answer to this is teamwork, and research teams are now bigger than they were.

A second approach is modularity. A laptop is built from simpler standalone modules, such as CPU, the keyboard, the OS and the data drive. Smaller teams can work on these sub-products.

But some knowledge is hard to shift. It is easier to move copper from mines in Chile to factories in Korea than to move the manufacturing know-how from Korea to Chile. The most complex products require elaborate networks of teamwork, and can be made in only a few places.

Over 20 years ago, Michael Kremer came up with the “The O-ring Theory of Economic Development”. The title refers to the seal that failed in the Challenger space shuttle tragedy. Lots of things (meals, music groups) are only as good as their weakest link.

The consequence is that the most skilled workers collaborate with each other, and have access to the best equipment. Consequential errors are reduced and inequality increases. This is a trend that is unlikely to be reversed.

Get fracking

The Economist reported that fracking has finally been given the go-ahead in the UK. Lancashire County Council have given Cuadrilla permission to drill at a single site near Blackpool. ((Planning permission has been given, but the councillors still have to approve the decision))

An American-style shale boom will still have to clear a few more fences however:

- while in theory the shale in the north could produce 50 years worth of gas, UK geography is less favourable than in the US

- much of the shale is beneath densely populated areas, valuable agricultural land, or in national parks

- perhaps as little as 1-2% is extractable (which is only one year’s supply, and no bonanza)

- mineral rights belong to the Crown, so local landowners can’t be bribed to give fracking the go-ahead

- public opposition is easy to organise near towns, or areas of natural beauty, and the public as a whole is lukewarm to neutral on the subject

- the planning process through local councils and government departments can take up to two years

Amber Rudd, the new energy secretary, is trying to cut the red tape. Local councils can now keep all of the business rates from fracking, up from half last year, which may make planning permission easier to obtain. But it won’t remove any of the other obstacles.

Alternative Venture Capital

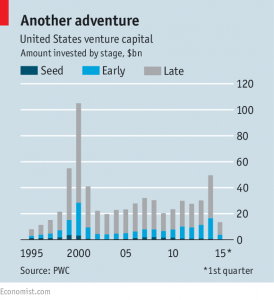

The Economist also reported on the competition that the current US venture capital (VC) boom – the biggest since the dot com bubble – has attracted.

VC is almost unchanged since its emergence in the 1950s. The industry is dominated by partnerships which provide three things:

- cash

- experienced board members

- access to industry connections

This makes the sector not “scalable” – firms can’t grow quickly (indeed, adding more partners tends to reduce returns, as investment by committee becomes more risk-averse).

There are four other factors affecting the VC market:

- the falling cost of creating a startup – cloud computing means that firms come looking for $50K, not $5M. This is not enough for VCs to be interested.

- perversely, at stage two – going global, startups now need lots of money, and quickly.

- startups are also more reluctant to go public at an early stage, so more private capital is needed.

- low returns on other investments makes VC look attractive

There are four main rivals to traditional VC partnerships at the early stage:

- “angels” – rich individuals who put money directly into startups. The US now has more than 300,000.

- crowdfunding websites

- “accelerators” such as Y Combinator and Techstars, which invest small sums startups before taking them to VCs later

- some VC firms have taken on the characteristics of accelerators by limiting the size and number of their investments; these are known as “micro funds”

At the “late stage”, big institutional investors like Fidelity and TPG, a private-equity firm, are providing money directly, like a one-stop IPO.

In between, online media is increasing competition between VC firms by offering more transparency on deals. Startups are also more connected to each other and seek out the best VC brands.

As more and more money chases the best deals at ever-higher valuations, casualties will be inevitable.

True contrarian investing

Over in MoneyWeek, Andrew Van Sickle took a look at what it takes to be a true contrarian investor.

Most people like to describe themselves as contrarian. It sounds heroic, and indeed many of the world most famous investors (Buffett, Soros etc.) are often described in this way. But in practice, most people are influenced by the herd.

Jeff Macke says that apart from the mental strain, contrarian investing doesn’t work. Macke looked at a CNN poll that dates back to 1974. respondents are asked how well things are going in the US, on a four point scale.

Macke’s experiment involved buying at each decades low point, then closing the position after 12 months. Similarly, the high point of sentiment would be shorted, and the position closed after a year. The results were bad: $1000 became $929 over 40 years, whereas the S&P 500 grew by a factor of 26.

Barry Ritholz says that market sentiment is self-reinforcing. In a football ground, the fans cheer when the team does well, and the cheering helps the team to do well. Betting against the crowd would not work most of the time.

A true contrarian needs to be able to identify the extremes of sentiment that might indicate turning points. As we noted last week, Greenspan identified “irrational exuberance” in 1996, but the market went up for another 39 months.

The aim is to go against the herd to capture value that the herd is ignoring. This may sound familiar – the common name for it is value investing. Buying shares when they are cheap has always been the best long-term strategy.

Bitcoin

Finally, following last week’s article on Bitcoin, I came across a useful infographic on Twitter. ((There are many such infographics – Google them – but the one I found doesn’t appear to be searchable, so I can’t credit the author; if anyone can find me a link I would be grateful))

Here are a few highlights. We’ll start with the 10 biggest companies that accept Bitcoin:

Here are the 5 countries which use Bitcoin the most:

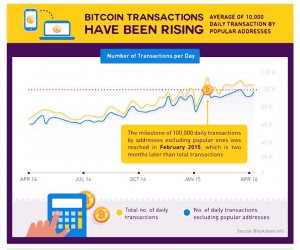

The rate of transactions is rising steadily:

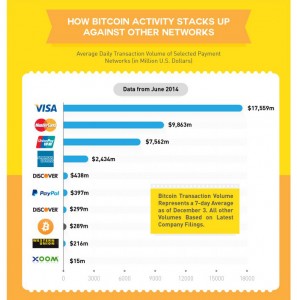

The network is still dwarfed by the credit cards, but it is catching up with more widely known online systems, such as PayPal:

But when you look at what the transactions are, it’s not too impressive (mostly gift cards and IT kit):

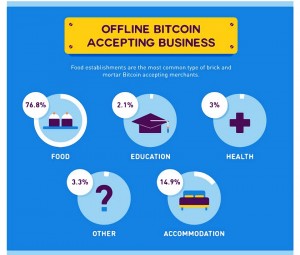

Offline, it looks like there isn’t much you can do except buy a coffee:

So in conclusion, we’re still some way from mainstream, real-world acceptance.

Until next time.