Weekly Roundup, 2nd March 2020

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup with what has become the big story once again – the coronavirus.

Contents

Not a panic

In his first Bloomberg newsletter of last week, John Authers was clear that the market selloff was not panic.

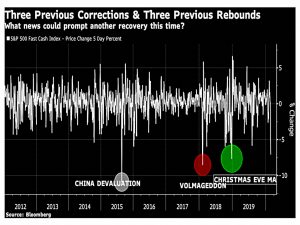

- The recent fall is the fourth drop of more than 7% since 2011.

Whilst the other three were followed by rapid rebounds, this time it’s harder to see how -for example – intervention by the Fed can make much difference.

The 10-year Treasury yield hit an all-time low on Tuesday, and futures markets are now pricing in two rate cuts (of 25 bps) before the Presidential election in November.

- Not that rate cuts will help much either against a virus or in what is already a very low interest rate environment).

Hong Kong has decided to implement helicopter money, and I’m interested to see how that goes.

This is a very unusual “correction” that is aiming to correct economic expectations in the light of news, rather than excesses in the market.

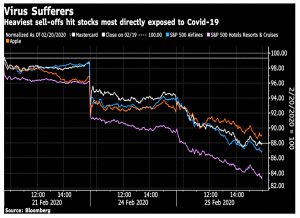

John notes that losses are worst in the sectors you would imagine (travel-related) and companies that have warned of future impacts.

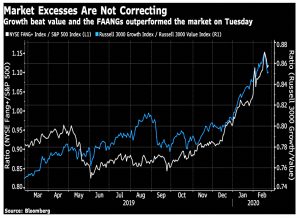

[On Tuesday] the NYSE Fang+ index lightly outperformed the S&P for the day, while growth stocks did slightly better than value.

Bitcoin fell and gold faltered after a good run.

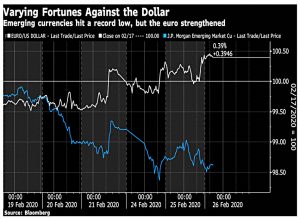

- And the euro (with one of the worst outbreaks in Italy) surprisingly strengthened against the “safe-haven” dollar.

The best explanation for this may be that investors are reducing their risk by closing out carry trades, which means buying back euros and selling off exposures to emerging market currencies.

Though this is no panic, John feels that underlying issues remain (beyond the virus):

This continues to look like a wildly top-heavy stock market supported only by extreme valuations in the bond market.

As you know, markets continued to fall throughout the week and things look much more like a panic by now.

The rising cost of care

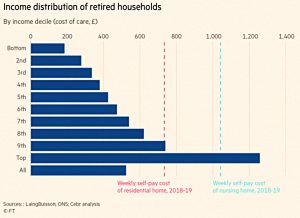

In the FT’s Chart That Tells A Story, Lindsay Cook looked at the rising cost of care.

- A residential home now averages £750 a week, and a nursing home £1,050.

The average stay in a residential care home is now 30 months. For nursing homes, the average stay is 16 months.

These costs are beyond the income of the 90th percentile of pensioners.

- The implication is that savings (including pensions and property) will have to be used instead.

But many pensioners are without savings and will need to rely on the state.

Things are likely to get worse over the next decade as the squeezed generation – too young for DB pensions (outside of the state sector) and not young enough for auto-enrolment – starts to retire.

In 2018, the average employer contribution to defined contribution schemes was 2.3 per cent compared with 16.2 per cent for defined benefit schemes. Employees paid 2.7 per cent to defined contribution schemes.

Family Investment Companies

Last year I looked into setting up a Family Investment Company (FIC).

- In the end, my family couldn’t come up with enough cash to get one started.

It seems I had a lucky escape, as Stefan Wagstyl reports in the FT that HMRC now has a special unit looking into the use of FICs.

- The comments section on that FT article is worth checking out – people are not happy.

HMRC previously set up a high net worth unit in 2009 to focus on the 7,000 or so people who have £20M or more in assets.

- The existence of the FIC unit – within the Wealthy and Mid-sized Compliance Directorate – was revealed after a freedom of information request was filed by Pinsent Masons PR.

HMRC said:

The Family Investment Company team was established . . . in April 2019 to look at FICs and do a quantitative and qualitative review into any tax risks associated with them with a focus on inheritance tax implications.

The team’s work is exploratory at this stage and as such, we would not like to share any more details. [Doing so] would allow opportunistic individuals and would-be avoiders [to] identify where HMRC is devoting resources and arrange their activities to escape challenge.

Since FICs don’t have any special tax advantages over regular companies, I’m not clear what the problem is.

Pension charges

With an article by Josephine Cumbo, the FT has launched a campaign for clearer pension charges.

- They asked Holly Mackay from Boring Money to analyse current charges for them.

Typical fees for investing a £1m pension fund into drawdown will cost between 2 and 2.5 per cent of your pot per year for a fully advised service, and between 0.5 and 1.25 per cent on a DIY platform.

My target is even lower, at 0.3% to 0.4%, though my individual pension pots are all smaller than £1M.

- At £1M, 0.3% would be a realistic target.

Clarity is good and I’m all for the FT campaign – but what we really need are cheaper pensions.

- Given the scale economies open to large providers, DIY SIPPs shouldn’t be the cheapest route.

Buffett’s performance

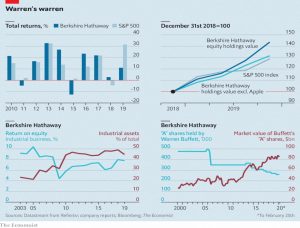

Following on from our review last week of Warren Buffett’s Annual Letter, the Economist looked at the recent performance of Berkshire Hathaway.

After years of mostly level-pegging or outperforming the broader market, Berkshire’s shares did only one-third as well as the soaring S&P 500 index last year.

As we noted last week, Buffett objects to the recent change which forces him to book unrealised changes in the value of BRK’s listed holdings as earnings.

- But he hasn’t been consistent about what the alternative measure should be.

At points he has endorsed tracking book value and at other times “operating earnings”, a proxy for the cash generated by the businesses Berkshire owns outright (plus the dividends from minority stakes).

The Economist splits BRK into two parts:

- Financials (insurance and listed stocks), and

- Industrials (railroads and manufacturers)

The second group has grown as a proportion of BRK (now close to half) and they have a low return on equity (8%), so they hold BRK’s performance back.

Benchmarks

Buttonwood looked at benchmarks, and why active bond funds can beat theirs, but active equity funds find this difficult.

- The sum of active stock funds (which deviate individually from the index) is the index itself.

So the average performance after subtracting fees is lower than the index.

- Passive stock funds underperform too, but their costs are lower so they underperform by less and on average beat the average active fund.

In theory, active funds could trade ahead of passive funds when the composition of an index is about to change, and in theory, outperform them.

In practice, the turnover in stocks within equity indices is not large enough to handicap the passive funds.

But bonds have an average life of six years, and so the makeup of bond indices changes a lot. In addition:

A lot of institutional investors are constrained in what kind of bonds they are allowed (or need) to hold. They may be barred from holding corporate bonds or bonds that are not rated investment grade. Or they may need to hold bonds of certain maturities for regulatory reasons.

Jamil Baz, Helen Guo, Ravi Mattu and James Moore of PIMCO put the proportion of bonds held by such “non-economic” players at around half.

A third point is that bigger (and therefore riskier) issuers of bonds are weighted more heavily in the indices.

Tiling against each of these flaws means that active bond fund managers can win.

Quick links

I have just four for you this week, the first two from the same source:

- Musings on Markets looked at the market meltdown

- And provided Data Update number 5, on Relative Risk and Hurdle Rates

- UK Value Investor wondered whether Diageo’s share price was too high

- And (amazingly) the FT wasn’t too keen on Piketty’s new book.

Until next time.