Weekly Roundup, 18th May 2020

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the Economist, where they were working out the costs of the lockdown.

Lockdown costs

The Economist was clear that the economic impact of the pandemic will last for a lot longer than the public health threat.

- In the absence of a vaccine, or even plausible treatment, I’m not so sure about that – I think they might both hang around for quite a while.

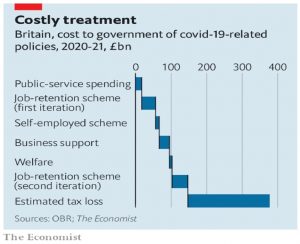

The bar that leaps out from the chart above is that the tax loss is double the impact of the direct spending, despite more than one in five workers now being attached to some form of government support system.

- Hence the desire to get back to work those who can operate safely.

It might not be so easy, however.

- I think Rishi set the bar too high at 80% of wages.

With nothing to spend money on other than food and drink, I think a lot of people will fancy the summer off if they have that amount of money coming in.

How to pay for it

In the FT, Emma Agyemang speculated about the tax rises that might be used to pay for all this spending.

- Her starting point was a leaked Treasury document with a shopping list of potential changes.

The Tory manifesto excluded raises to income tax, NIC and VAT – plus the state pension triple lock – but some commentators think that voters might for once understand if election promised were broken.

- Personally, I think that tax rises will have to wait until we have an economic recovery, but let’s indulge ourselves for a moment.

A penny on income tax (or possibly 1% on the basic rate, 3% on the 40% rate and 5% on the 45% rate) would raise a lot of money.

- The Chancellor might also introduce such changes as temporary (say for five years).

There will inevitably be calls to focus exclusively on the well-paid, but unfortunately, there aren’t enough of them.

- A penny on basic rate raises almost five times as much as a penny on the higher rate, and fifty times the amount raised by a penny on the 45% rate.

There have also been suggestions that the tax-free allowance might become a 10% or 15% band.

- But this would mainly hit the lowest earners, so I can’t see this.

On national insurance, there are three obvious options:

- Scrap the upper earnings limit, so that everyone pays 12% on all earnings.

- This effectively increases the 40% band from 42% to 52%.

- Add a surcharge to NICs for either/both of the NHS or a general social care fund.

- The latter could plausibly be restricted to the over-40s, which could make it more popular with the mainstream media.

- Add NICs to wages for workers older than the state pension age.

- This is morally dubious since NICs, in theory, finance the state pension, and many people will have already paid in for more years than the maximum qualification of 35.

The self-employed can expect to pay more in NICs (they pay 9% at the moment).

- Rishi Sunak said as much when he extended the furlough scheme to the self-employed.

Moving on the pensions, higher rate income tax relief could go.

- And the annual and lifetime allowances might shrink yet again.

And of course, the triple lock on the state pension could go, even though the UK state pension is the lowest in Europe.

A more creative change would be to replace inheritance tax with some kind of gift tax (or capital transfer tax, as the UK had until the 1980s).

- The key here would be the level of allowances (annual and lifetime).

And CGT could be aligned with income tax.

- There’s even talk of new property taxes or a general wealth tax.

I can’t see these happening as the UK economy is too dependent on a buoyant property market.

So the Chancellor is spoilt for choice in terms of options, though I doubt more than a quarter of these changes will actually happen.

- The real problem is not introducing new taxes, it’s persuading people to behave so that the new taxes raise more money than the old ones.

Inequality

The Economist also had a couple of articles about inequality.

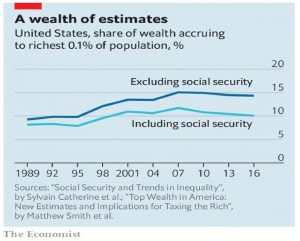

- The first looked at new research which suggests that rather than having made out like bandits since 2000, the top 0.1% in the US has merely stood still.

Measuring wealth is harder than it may seem. People are liable to under-report their asset holdings on official surveys, whereas it is hard to measure the true value of things like private companies and art works.

So these new studies reverse engineer wealth from the income it produces.

Previous estimates have relied on the assumption that all people receive the same rates of return on a given type of investment. That may be misleading. The rich tend to plump for riskier investments, which command higher rates of return.

Which of course implies that their asset base is smaller than previously thought.

A second study claims that it is unfair to count only private wealth.

- Claims on future state payments (pensions, or what they call Social Security in the US) should also be included.

This is my preferred approach, and it closes the gap between rich and poor yet further.

- The Economist notes that based on private wealth alone, Sweden has very high inequality, which the poor can tolerate because of a generous cradle-to-grave welfare system.

The second article explained that the pandemic could actually lower inequality eventually.

It doesn’t look like that in the sort term:

Covid-19 seems to have hit poorer neighbourhoods harder. Low-wage earners are often less able to work from home or maintain social distancing. Interruptions to schooling widen the gaps in achievement between children. Meanwhile, workers on the lower rungs of the income ladder have borne the brunt of job losses.

So the big danger is that temporary job losses become permanent.

- But disruptive events usually lead to more equal distributions of income and wealth.

Thomas Piketty points out that high levels of inequality in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were reduced by the calamitous events of the period from 1914 to 1945. Only four forces have ever managed to reduce inequality in a sustained way: war, revolution, state failure and pandemic.

It’s hard to see wages rising because of a shortage of workers (as after the Black Death).

- If anything, social distancing will encourage more robots and fewer humans.

Nor should we see a repeat of the 90% stock market crash from the 1930s depression.

- But the debts we are racking up will need to be repaid, and the rich are likely to foot a greater proportion of the bill.

Redwood portfolio

John Redwood provided his regular update on the ETF portfolio he runs for the FT.

- He’s at 20% cash.

As the virus started to spread, I reduced risk in the FT Fund as much as I could. I gave up on euro area exposure some time ago. I cut the exposure to property.

I kept the bulk of thereduced share exposure in the US. More recently, I have added to the fund’s technology holdings.

I am also underweight Europe and property (excluding my home).

- I also have some tech, but nowhere near as much as John.

The US is now up to around two-thirds of his fund – that’s scarily high for me.

- John is down 5% YTD, and I’m just behind him at -5.3% as I write this.

John has also restructured the bond part of the portfolio:

I have sold the corporate bond ETFs, as I am expecting more downgrades and bankruptcies to trouble these markets. I have increased the fund’s holdings in US Treasuries.

I agree with John that government bonds are a better bet than corporate, but I can’t stomach the low (below inflation) yields.

- Luckily, I can use cash and DB pensions as proxies.

Risk parity

The Economist noted that risk parity strategies didn’t do well during the March crash.

“The pandemic was a strange beast that I didn’t have an edge wrestling with,” says Ray Dalio, founder of Bridgewater Associates.

Bridgewater reported losses of between 7% and 21% across its various funds for 1Q20 (still less than the major stock indices).

The newspaper explains the theory behind risk parity:

To balance holdings of relatively volatile stocks with government bonds—in times of market stress bonds usually rise in value, offsetting losses from stocks. But that means less exposure to equities, which tend to have higher returns. Bridgewater’s innovation was to keep a high allocation of stocks, but to borrow to buy safe long-dated bonds.

The approach performed very well during the 2008 crisis, and more than $1trn in assets are now managed this way.

- The problem this time was the period when bonds and stocks fell together, in late March.

I use risk parity as the basis for my own portfolio, but with a few differences:

- Since risk parity portfolios hold a lot of bonds, they are low return (in absolute terms – they have high risk-adjusted returns).

- I aim to hold more stocks, though my high allocation to expensive London property means that I have never (will never) reach my target of 75% stocks.

- I use very long-term values for returns, volatilities and correlations between assets.

- I don’t use leverage.

- The combination of short-term rebalancing and very high leverage is usually to blame for high-profile blowups of hedge funds and risk-parity firms.

- During period of high volatility, I sell some stocks (from the trend-following portion of my portfolio) but I don’t covert the cash this generates immediately into bonds.

- This is how I avoided the double-whammy in late March.

Quick links

I have just three for you this week:

- Musing on markets compared strategies through the crisis – Value vs Growth, Active vs Passive, Small Cap vs Large

- UK Value Investor had some tips on investing in a coronavirus world, and

- The Economist had an ode to the shopping mall.

Until next time.

RE: 80% – I reckon you are correct.

Just to get a sense of peoples current thinking: at one of the recent daily No 10 briefings iirc a member of the public asked if he would get money to buy a car as public transport should not now be used

Perhaps the new “Pick for Britain” appeal will prove me wrong – let’s see.