Weekly Roundup, 1st July 2015

The pages of the financial press are dominated this week by the possibility / likelihood of Grexit, but as I write this it seems like a story that it is either too early or too late to cover. ((Greece has just missed its IMF payment deadline, and the referendum on whether to accept the troika’s demands is only four days away))

Instead we will begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with the chart that tells a story.

Contents

Tax credits

Adam Palin looked at tax credits, which were introduced in 2003-04 at a level of £16bn annually and rose steadily to a peak of £29bn in 2011-12. Since then they have declined slightly as the coalition government has tightened qualification.

Tax credits are actually welfare payments to low-wage workers (working tax credit, WTC) and parents, including the unemployed (child tax credit, CTC).

- CTC is £2.8K per child plus £545, and is tapered at 41% per pound earned over £16K

- WTC starts at £2K, and the 41% taper begins on earnings over £6.4K

- 4.5M families receive tax credits, down from 6.3M in 2010-11

- the decline is almost entirely within working families

- the total paid out has declined only slightly, since the number of families claiming larger amounts has not changed much

The chart shows the amount paid out each year to the various claimant groups.

Further cuts to payments are expected in the July Budget. Returning to the original 2003-04 levels of payment (adjusted for inflation) could save £5bn of the required £12bn from the welfare budget.

Bond proxies

Terry Smith took a look at bond proxies – companies like consumer staples and utilities with safe and predictable returns, but also with higher yields than most bonds, and the potential for yield growth over time.

Bond markets are in a bull market / bubble inflated by two things:

- QE, which allows central banks to buy their own their government’s bonds, and

- a close-to-zero interest rate policy in the absence of inflation.

As bond yields fall, more investors are forced into equities, and particular bond proxies.

Terry began with a couple of quotes from Warren Buffet, of which this is the second: “The primary test of managerial economic performance is the achievement of a high earnings rate on equity capital employed (without undue leverage, accounting gimmickry etc) and not the achievement of consistent gains in earnings per share.”

The most common criticism of Buffett-style investing is that companies like this are too expensive. This concern is being voiced once again in anticipation of interest rate rises, starting in the US.

Terry thinks that the impact depends on how much interest rates rise. In a weak recovery and a disinflationary environment, he expects rate rises to be slower and more gradual than in previous recoveries.

Short-term rates will rise in the end, but long-term rates are more important to bonds and equities, and 30-year US Treasuries already yield more than 3%. Terry doesn’t expect this to shift much.

The second question is what would those fleeing bond proxies do with the money? Bonds and other, more cyclical – and in Buffet’s terms, lower-quality – equities don’t look cheap.

Terry believes that long-term investors (that is, all of us) should stick with the bond proxies. Return on capital is key.

As Charlie Munger says: “It’s hard for a stock to earn a much better return than the business which underlies it … a business [that] earns 18% … over 20 or 30 years, … you’ll end up with one hell of a result.”

To demonstrate, Terry compares two companies held over 40 years:

- A has return on capital (ROCE) of 20%, and can’t be bought cheap – say at 4 times book value; further, when you sell in 40 years time, the rating has halved to 2 times book

- B (a market proxy) earns 10% ROCE, and can be bought at 2 times book; when you come to sell the rating has improved and you can sell at 4 times book

A still produces a compound 18% pa, whereas B only manages 12% pa. Stick with Warren, and with ROCE.

Mini-bonds

And so to another substitute for bonds, but this time a bad one. Judith Evans looked at the wild west of the mini-bond market.

Thousands of private investors have bought mini-bonds over the past 2 years, attracted by potential high yields. But mini-bonds are unregulated, can’t be sold and don’t come with compensation in the event of failure.

International Portfolio Managers (IPM), the security trustee for Secured Energy Bonds (SEB), which lost more than 900 UK private investors £7M when it went into administration in January, is promoting a new mini-bond.

It emerged that 20% of the money raised by SEB went on launch costs – ten times the usual amount – while most of the rest was transferred to an Australian parent company to clear debts and to be used as working capital, in contravention of the terms of the mini-bond prospectus.

Now Providence Bonds II plc aims to raise £5m at 7.5% yield on behalf of Providence Global Ltd, a private Miami-based financial services firm. Providence will use the cash in its invoice financing operations in Brazil, the US, Asia and a new operation in the UK.

These aren’t bonds as we know them, and the promise of 7.5% isn’t enough to cover the risks. Don’t buy them.

The psychology of saving

Tim Harford took a look at the impact of behavioural economics on pensions. Behavioural economics is the branch of economics that tries to be more realistic by taking psychology seriously.

One of its greatest successes is pensions. Like much of personal finance, the pensions problem has two characteristics:

- there is a large behaviour gap between what we should do and what we actually do

- the best way to close the gap is a very simple thing: save more and more regularly (into simple low-cost funds, largely trackers)

Outside of money, the obvious parallel is health. Everybody knows that smoking is bad, and most people know that vegetables and exercise are better than fast food and reality TV. But many (in the case of smoking) or most (in the case of health) ignore what’s best for them, and take the short-term boost.

There is now evidence that taxes on cigarettes please both smokers and potential smokers by making them more likely to quit or less likely to start. Taxing fat and the causes of fat still seems to be a long way off, as the inclusivity lobby remains in denial on this one.

Back to pensions. The biggest recent breakthrough has been automatic workplace enrolment. Tax advantages and employer matched contributions weren’t enough to convince people to save for the future, but making it the default option (opt-out rather than opt-in) seems to be doing the trick. A classic “nudge”.

In the US they have added “Save More Tomorrow”, where a portion of future pay rises is diverted to pensions. The idea is to get the starting contributions of 2% or 3% up to the required 12% to 15% range.

Choosing the level is important – too high will jolt people into opting out, while too low might drag down those who would have made better contributions of their own volition.

A second problem is the desire of the corporate HR department to continually remind employees of the generous pension subsidy being provided. This is likely to increase anxiety and reduce the effectiveness of the initial nudge.

One way to overcome this would be to focus on the happy outcomes from pension savings (eg. cruises) rather than the maths. But it’s a better problem to have than nobody saving in the first place.

US pension deficits

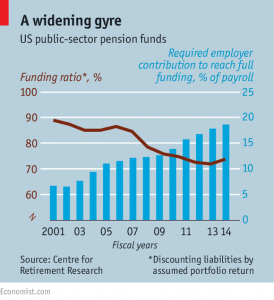

In the Economist, Buttonwood looked at the persistence of pension deficits in the US. America’s public-sector plans hold more than 50% equities, and the record highs on the S&P 500 might be expected to be good news for them.

But the latest report from the Centre for Retirement Research (CRR) at Boston College estimates that the funding ratio (assets / liabilities) has risen only from 72% in 2013 to 74% in 2014. The bottom fifth of schemes are at less than 60%.

It’s actually much worse than that. Future payments are discounted not by long-term corporate bond yields (around 4%) but by the expected return on pension scheme investments (which trustees estimate to be 7.6%!).

Pretending that it is cheaper for the public sector to fund a pension than it is for the private sector shrinks the deficit from $3.9trn to $1.1trn. ((If anything, it should be a bit more expensive as public-sector workers live slightly longer)) Using the private sector measure, public pensions are just 45% funded.

The private sector has tried to tackle the problem over the past 20 years by closing final salary schemes. US firms still have an aggregate pension deficit of $389 bn ($585 bn including health care). But it does appear on balance-sheets.

The public-sector shortfall is being swept under the carpet, because nobody wants to tackle the problem. Unions don’t want to see benefits cut, politicians don’t want to raise taxes. And the schemes won’t run out of cash for decades.

Fixing the hole needs ever higher contribution rates: up from 7% fifteen years ago to 19% now. And states only need to make seven-eighths of the required payment. So the hole keeps getting bigger.

Growth and interest rates

Over at MoneyWeek, they wondered whether higher interest rates have to be bad for growth. The Federal Reserve’s interest-rate-setting met again last week, and declined to raise rates for the first time in nine years.

Janet Yellen said the labour market had strengthened a bit more evidence that the recovery was gathering pace was needed. Many people expect a rise in September, but it could as easily be delayed until 2016.

Normally, US stocks wobble before the first rate hike but then recover as the rises are taken as evidence of a stronger economy. This time might be different, as high private and public debt means that higher rates could impact growth.

Or not. Some economists wonder whether all the money printing by central banks has, rather than stoke inflation and avoid a slump, done the opposite. QE and ultra low interest rates appear to have been deflationary, at least in the short-term.

Low rates keep zombie firms – those that should be dead – alive, and encourage investment in dubious ventures (eg. the shale oil boom), thereby increasing supply. Low rates of interest make savers less willing to spend, reducing demand.

By keeping supply higher than demand, current conditions keep prices low. So higher rates could plausibly increase growth (and inflation). Which could be good news for stocks.

Legitcoin

Finally, it seems that everywhere I look these days I see a Bitcoin article, despite the exchange rate still languishing around the $200 mark.

This week’s story is from the Evening Standard, where Joshi Herrmann interviewed Nathaniel Popper about his book Digital Gold: The Untold Story of Bitcoin.

[amazon text=Amazon&asin=0241180619&text=Digital Gold?&template=thumbnail]

Popper is no fanboy – he owns only two Bitcoins personally – but he is enthusiastic about the technology. As you’ll remember from our previous article on the subject, the advantages of Bitcoin are:

- anonymity – like cash, you don’t need to know or trust the person you are transacting with, and you don’t need to each rely on a common third party for authentication

- cost – transactions cost a third of a penny, rather than the typical 3% credit card charge

- resilience – the blockchain transaction validation method doesn’t have a single point of failure

Wall Street and the City are now taking a serious look at how Bitcoin and its blockchain technology could be used in conventional finance.

- Barclays have just announced a deal with Safello, which runs a Bitcoin exchange and has been part of the bank’s financial tech accelerator in London.

- In April, UBS said it was opening a research “lab” in its Canary Wharf office to do something similar.

- In 2014 Goldman Sachs hosted a conference to explore virtual currencies.

- London has potential as a Bitcoin hub – George Osborne has allocated £10M to support research in the area.

Popper says there are two areas where the banks think Bitcoin might be useful:

- clearing and settlement, where Bitcoin (or just the blockchain) would cut out the middlemen, including lawyers

- consumer payments, where Visa, Mastercard and Amex could be disrupted

Until next time.