Weekly Roundup, 1st November 2021

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup with …

Inflation

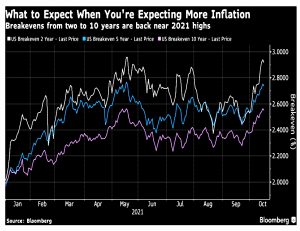

John Authers wrote that the markets now accept that inflation is more than a blip.

- Breakevens (from inflation-linked and regular bonds) between 2 and 10 years are back near their 2021 highs.

John points out that the breakevens tend to follow the short-term oil price:

Marc Chandler of Bannockburn Global Forex said:

The rise of oil and gas prices is not like other price increases. They are essential inputs to agriculture (especially fertilizers and pesticides), manufacturing, and transportation.

On the one hand, this sounds like it is inflationary. On the other hand, the dramatic increase in prices should be considered a tax on consumption.

And like other commodities, high prices tend to cure high prices, so the long-term impact is likely deflationary.

Inflation expectations

Joachim Klement looked at a new paper on inflation expectations.

Jeremy Rudd is an economist at the Federal Reserve and he has published a paper that methodically analyses the theoretical and empirical validation of the assumption that inflation expectations are a major driving force of future inflation.

The central concept is that if people expect inflation to rise then workers will demand higher wages and firms will increase prices to protect their margins.

- The flaw is that workers are assumed to have no “money illusion” (they understand that inflation will reduce their nominal wages) whereas employers use current wages and inflation rather than future estimates.

Back in the real world, we know that workers and employers both are subject to money illusion and do not correctly account for short-term inflation and we also know that employers care very much about future wages and wage inflation.

There’s also a mismatch between economics and monetary policy.

- The former uses short-term inflation expectations whilst the latter targets long-term expectations.

It seems that workers and households form their views on wages and inflation not on future expected inflation, but rather on the recent deviation of inflation from long-term historic averages.

If consumers experience a bout of higher than usual inflation, they will ask for higher wages. If inflation calms down again, wage inflation declines because workers ask for fewer wage increases.

As inflation surges (whether in a transitory manner or not), this is not good news.

- The decline of union power since the last bout of serious inflation in the 1970s might make it more difficult for workers to get pay raises, but they are likely to ask for them.

Letting inflation run above 2% for an extended period of time could leave long-term inflation expectations well-anchored, but still increase wage inflation pressures and create a 1970s-style wage-price spiral simply because every year, recent inflation is above historic averages.

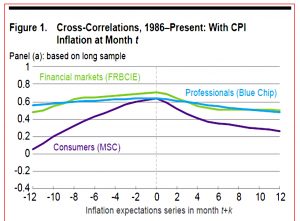

John Authers notes that there has been zero correlation between consumer inflation expectations and actual rates a year later since 1986.

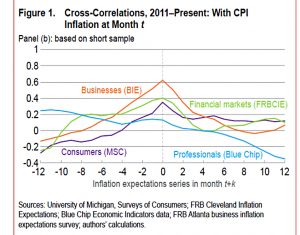

The financial markets and professionals do a better job, although the correlation 12 months ahead of time is still a bit less than 60%. Over the last decade, correlations have deteriorated further.

John says:

I suspect these awful outcomes reflect the conditions of the post-crisis decade, when people kept bracing for a resumption of inflation that kept not happening.

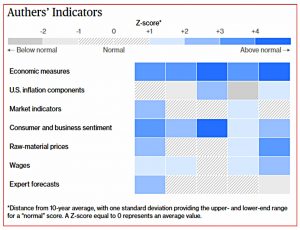

Not much has changed with John’s own set of inflation indicators.

Wage settlements are picking up, as are prices of raw materials.

Index funds

Buttonwood looked at a new book on index funds by Robin Wigglesworth of the FT.

“Trillions”chronicles the rise of passive funds from 1960s academic curiosity to 1970s commercial flop and then runaway success in the 2000s. It estimates that over $26trn—more than a year’s economic output in America—is now lodged in such funds.

The index story has become very familiar since the 2008 financial crisis.

- Index funds are cheap because they are systematic, which means that on average they outperform the more expensive actively-managed funds, which must find the high salaries of their human managers.

Passive funds have done particularly well since 2008, since they are usually market-cap weighted, and the largest stocks in the largest markets have done unusually well in recent years.

- 40% of fund assets in the US are now passive.

There are three potential and related issues:

- A transfer of power to the indexing companies (MSCI, S&P and FTSE)

- A similar dominance by the main passive fund providers (BlackRock, StateStreet and Vanguard now own more than 20% of large listed US firms)

- This leads to corporate governance issues where the fund providers abstain on key issues.

- There are also competition concerns that firms within the same providers’ portfolios might not compete aggressively against each other.

- The “dumb money” issue – passive funds are not price-sensitive and therefore don’t contribute to the price discovery process

- This is particularly an issue in under-represented stocks (eg. small caps).

- A related complaint comes from active managers who view passives as “free-riders” on their research.

Against this, the recent renaissance of retail investing should lead to more price-discovery (even if some of this will now be meme-driven).

- But at some point, there could be too much passive cash for the good of the markets.

Fund fees

Sticking with the theme of fund fees, Merryn Somerset Webb said that they matter more than “skin in the game” when it comes to choosing a fund manager.

- There is a potential conflict of interest when active managers don’t have money in their own funds:

Their main interest is not so much good performance in itself but in growing the assets under management: the more they manage the higher the absolute value of the percentage take.

This generally requires decent performance to begin with, but then the marketing machine can kick in.

- Many “star” managers follow a similar trajectory – their style of investing works for a while and their fund grows large, at which point the dominant style changes and they underperform until investors catch on and sell.

A great example of investor underperformance is the Magellan fund run by Peter Lynch.

- While Lynch was compounding the fund at close to 30% pa, the average investor showed such poor buy and sell timing that they actually lost money.

Interactive Investor has published a “skin in the game” report for the 100 funds on its recommended lists. (( A larger report is produced each year by a fund manager – possibly Cannacord Genuity ))

94 per cent of managers said they were invested in the fund they manage and 24 per cent said those investments came to more than £1m.

Merryn thinks this analysis can lead to awkward questions:

How on earth, in a business that is ostensibly highly competitive, can your profit margins be so high that you pay your managers so much that they can afford to have that much money in just one fund (no one holds just one fund…)?

As we noted above, cheaper funds with no expensive managers to pay, tend to outperform.

- And fees are much simpler to interpret than skin in the game.

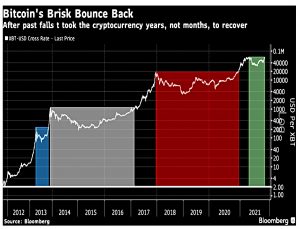

Bitcoin

As the first Bitcoin ETF was preparing to launch in the US (albeit a futures-based ETF rather than one which provides access to the spot price), BTC was pushing up against its all-time highs.

- John Authers looked at possible explanations other than ETF frenzy.

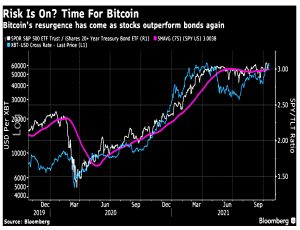

Bitcoin also appears to be behaving more and more like a “risk-on” asset, rising in price when stocks are doing well, bonds are doing badly, and people feel optimistic.

Interestingly, this runs counter to the other argument in favour of BTC as a safe haven store of value, protecting against inflation and dollar debasement.

Bitcoin’s peak earlier this year came roughly as stocks ended a protracted rally against bonds. The stocks/bonds relationship has been almost horizontal for six months, and is in recent days showing signs of breaking out to the upside — just as bitcoin also breaks upward.

This link to other asset classes need not prove reliable – BTC has only 12 years of history, and remains in the growth/speculation phase.

- The sentiment is more important than economic variables.

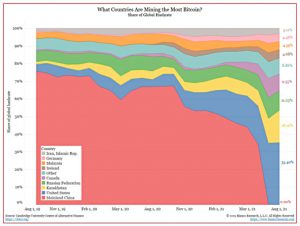

John quotes Jim Bianco (also from Bloomberg) on the reaction to the recent Chines crackdown on crypto mining as ” one of the most bullish things that has ever happened to crypto”:

Nearly 50% of the computing power (called hash rate) of the bitcoin blockchain, pulled the plug, packed up, and relocated to another country in a few months. And no one noticed! It signals an incredibly resilient system.

Part of me is inclined to agree, but in my head, I hear the old market saw “buy the rumour, sell the news”.

- Might the bitcoin ETF mark a local peak?

Quick Links

I have nine for you this week, the first three from The Economist:

- The Economist noted that servicing electric cars is different

- And wrote about the activist investor targeting Shell

- And investigated the Great Britsh Battery Bonanza.

- MarketWatch did the math for Tesla’s stock price

- Alpha Architect looked at the role of factors in asset allocation

- And UK Dividend Stocks concluded that Next is well-positioned for the future.

- Joe Lonsdale said that the (US) Wealth Tax is a terrible idea

- Musings on Markets asked if the Billionaire Tax was the worst tax idea ever

- And Pragmatic Capitalism looked at whether hyperinflation is coming.

Until next time.