Weekly Roundup, 7th March 2023

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup with news.

Contents

News incorporation

Joachim Klement looked at the speed with which news about stocks is incorporated into the stock price.

- When the reaction is slow, there is an opportunity for investors to take advantage.

Sometimes, a company may issue positive news, but the share price doesn’t rise. Instead, it drops or moves hardly at all. In my experience, this happens particularly often in a bear market.

A new study from the University of Reading has found that investing in shares that incorporate new slowly makes 1% a month more than the S&P 500 (assuming 0.25% trading costs).

Joachim puts the effect down to the limited attention of investors:

Stocks in the spotlight of investors tend to incorporate news quickly and efficiently. But other stocks do so much more slowly. Smaller stocks, less liquid stocks, stocks followed by fewer analysts and stocks less covered by the media [react more slowly].

So unlike the drunk looking for his lost keys next to the lamppost, look where there is less light.

A second article looked at a study of two behavioural finance effects: prospect theory and emotional states.

Additional gains create less and less ‘utility’ for the investor and thus increasing risk in the portfolio becomes less and less attractive. On the other hand, people who [have had] losses are risk-seeking. They are willing to increase risk in their portfolio even if that means incurring even larger losses just to get a chance to ‘break even’.

Also, investors in a good mood are risk-tolerant/risk-seeking, and those in a bad mood are risk-averse.

You would expect these two effects to be additive:

- People sitting on gains and in a good mood would take more risk than before.

- People sitting on losses and in a bad mood would be even less risky than before.

(You might also expect the two effects to be correlated, since sitting on gains would put most people in a good mood, etc).

The first effect is true – a good mood encourages those with gains to take more risks.

- But the second is not – a bad mood encourages people with losses to take even more risks.

This matches Joachim’s hunch about the effects of a bear market:

In a bear market, investors will try to find the next best investment that provides hope for a recovery in fortunes. But this promise is easier to find for stocks in the media or present in the minds of investors. Thus, in a bear market, investors sitting on losses will likely flock to large and mega cap stocks with good news.

Leaving less well-known and more poorly-covered stocks to react more slowly (and to provide opportunities).

Stock picking in the small- and mid-cap space should become easier, and the outperformance of active fund managers should increase as they recover from the bear market.

Baloney dot com

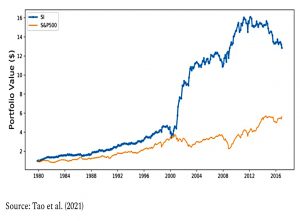

John Authers wrote about an update to one of his “favourite charts of all time”:

Philadelphia fund management group AJO Vista (Aronson+Johnson+Ortiz) has kept a chart of the returns you would make by consistently shorting the most expensive 10% of US stocks, and putting the money into the 10% cheapest.

This value strategy is based on trailing PE and is equal-weighted and sector-adjusted, using the largest 2000 US stocks.

John is particularly interested in the period when the strategy loses money.

I first saw this chart in 2000, when the-then AJO wanted to point out the madness of the internet craze, which it referred to as Baloney.com. There had been four periods of negative performance before 2000, the worst being the “Great Garbage Market” of 1968.

Since then we’ve had the 2008 crisis and the four years up to 2020, which was the longest period of underperformance.

In all cases, a huge snap back in favor of cheap stocks followed. If the past is any guide, it’s fair to expect cheap stocks to keep outperforming the rich ones for a while yet.

Flawed Core

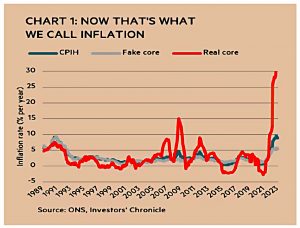

In the Investors’ Chronicle, Bearbull argues that our measure of core inflation is flawed.

The ONS uses a variant of the CPIH that simply excludes the contribution of price changes in energy, food, alcohol and tobacco.

CPIH is OK, adding housing costs (for owner occupiers) to the Consumer Prices index.

- The exclusions are not great, though.

Two of [these items] – food and energy – simply could not be excluded from a household budget, and one – fuel – has a history of bouncing around erratically.

BearBull proposes his own “real core” index:

The components are: food (41 per cent), clothing (9 per cent), housing costs (21 per cent), health (4 per cent), transport (8 per cent), fuels (17 per cent).

BearBull’s version of core has been racing away since late 2021 and is now at something like 35% (off the top of his chart).

- A lot of the difference is down to domestic gas and electricity charges (which largely can’t be avoided).

Arguably what’s most interesting is not the way that real core inflation is behaving at present but how it has behaved since the global financial crisis of 2008-09.

Things were different before then.

[BearBull core] trailed both the CPIH index and its core inflation offshoot for the best part of 20 years leading up to [the 2008] crisis.

But recently it has overtaken both, and that’s why people are so unhappy.

Savings rate

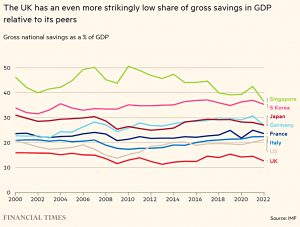

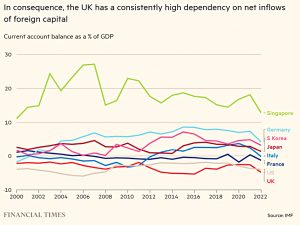

In the FT, Martin Wolf was arguing that Britain can learn from Singapore on savings.

Gross investment averaged a mere 17.1 per cent of UK gross domestic product from 2010 to 2022. This was lower than Italy’s 18.6 per cent, and the US’s 20.6 per cent. It was even further behind Germany’s 21.1 per cent and France’s 23.3 per cent. Korea’s 31.4 per cent seems from a different planet.

Things were the same even before the Brexit vote.

The underlying problem is that investment drives productivity which (along with population growth) drives GDP.

- And investment is financed by savings.

UK investment is heavily dependent on foreign savings. That is because its savings are even weaker than investment. This, too, is a chronic condition.

Between 2010 and 2022, UK gross national savings averaged a mere 13.3 per cent of GDP. The US average was 19.0 per cent and Italy’s was 19.8 per cent. Still further ahead were France, with 22.6 per cent and Germany, with 28.2 per cent. Korea’s averaged 35.7 per cent.

The dependence on foreign savings shows up in the current account deficit, which averaged 3.8% of GDP over the same period, and made up around a fifth of UK investment.

So:

- We need to retain the confidence of foreign investors, and

- A fair whack of the returns on the investment head abroad.

And if we saved more, we could keep more of the pie as well as make the pie bigger.

- We might even flip things around and start to accrue foreign assets.

This brings us to Singapore, which has a savings rate of 30% of GDP (and a current account surplus averaging 17.5% of GDP).

- Unfortunately, this arises from compulsory savings of 37% of wages into the “central provident fund”

Which makes our own (opt-out) workplace savings of 8% of salary (up to £50K pa) look pretty weak sauce.

- 8% is too low to fund an adequate pension, and I’ve long argued that we should move closer to 15% contributions – but I doubt very much that we could get close to 37%.

In fairness, Martin is only asking for a gradual rise to 20%, which I support.

- If that could fix the UK’s productivity problem, as well as provide decent retirement income, that would be great.

Pension Freedoms

We are in the run-up to the Budget, which makes it the silly season for outlandish tax suggestions.

- We’ve already had a proposed cap on ISAs (from the Resolution Foundation) and a wholesale revision of pensions tax advantages (from the IFS).

Now the Resolution Foundation is back, with the recommendation that the government should crack down on pension freedoms in order to stop “wealthy” people from retiring early.

- Private pensions are a big deal in the UK because the state pension remains so inadequate (despite the annual bleating about the triple lock).

The two features that the RF would like to “fix” are:

- the ability to take money at 55 (which is already scheduled to increase to 57 as the state pension age rises to 67 by 2028)

- the 25% tax-free lump sum (again – the IFS had a go at this a couple of weeks ago).

If Hunt wants to tempt retirees back (and dissuade more from retiring), I think he should scrap the LTA.

DIY investing

In FT Adviser, Sally Hickey wrote that the DIY investing market shrank by 8% last year.

- The data comes from Boring Money, which said that the value of assets owned by non-advised investors fell to £345 bn by the end of 2022.

Given the market falls last year, that’s not a massive shock.

- Indeed, the number of accounts increased somewhat, to reach an all-time high of 9.54 M (up from 5.7 M at the end of 2019).

Boring Money CEO Holly Mackay said:

Consumer sentiment remains very low, and although new money is not rushing in,

neither are we seeing people sell up en masse. Investors are largely sitting on their hands and riding it out, with new investors coming in albeit at slower rates than we’ve become accustomed to.

Nothing to see here, then.

Quick Links

I have four for you this week, the first two from The Economist:

- The newspaper said that The case against Google hinges on an antitrust “mistake”

- And reported that Investors are going nuts for ChatGPT-ish artificial intelligence

- Alpha Architect asked Does International Diversification Work?

- And looked at Intangibles and the Value Factor.

Until next time.