Weekly Roundup, 27th August 2019

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT with The Chart That Tells A Story, which this week was about the state pension.

Contents

State pension

Josephine Cumbo looked at the rumour that the state pension age will be raised to 75, which comes at a time when fewer people are claiming the pension.

- Since the suggestion to raise the age came from a right-wing think tank, rather than the central government, the seriousness with which it was treated in the mainstream press suggests a political motivation.

There are 12.6M people now claiming the state pension, 300K fewer than two years ago.

- The qualifying age has risen for both men and particularly women (who used to receive it five years early).

This has limited the number of new claimants from the baby boomer generation.

- I won’t qualify until I’m 67 and for people younger than me, the age qualification has already been raised to 68.

It seems clear that we won’t stop there, but future increases are likely to be linked to increases in life expectancy, which have stalled recently.

The key number to watch is the ratio of claimants to workers who are funding the payments.

- There is no central pot of money to throw off an income each year.

Increasing the qualifying age helps at both ends – fewer claimants and more workers.

The government has also committed to giving people 10 years notice of any change.

- Which means that my start date should be secure, and my partner’s date will be safe in a few months.

Recession-proof your portfolio

The inverted yield curve means that we’ve seen a rash of articles about how to cope with a recession.

- We published our own approach a couple of weeks ago.

This week it was the turn of the FT, in an article written by Siobhan Riding and Emma Agyemang.

The indicators they were watching included:

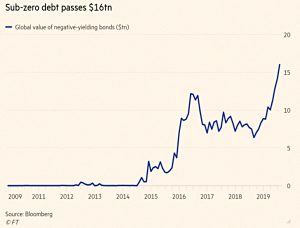

- negative bond yields

- negative interest on cash

- negative mortgages

- the US yield curve inversion

- the rising gold price

- the trade war, and

- a hard Brexit

Whether the inverted yield curve still works at such low interest rates is open to question, and even if it does, we could have a year or two to run, with plenty of room for a final melt-up in markets.

- I think this particularly the case because Trump has a presidential election to win next November.

The worry is that when the downturn comes, it could as drawn-out and protracted as the current recovery has been.

- The average series of cuts by the Fed during a recession is 5%, but with rates only at 2.25% to begin with, there’s no scope for that much intervention.

Tax cuts or even helicopter money might also be needed.

Suggestions for de-risking included gold, bonds, multi-asset funds, absolute return funds and cash – though it’s hard not to see bonds as risky themselves at present.

- Cash apparently now makes up 12% of the average portfolio.

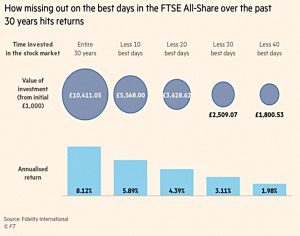

Full-on timing of the market was as usual not recommended.

Sectors that will suffer include housebuilders and banks.

Reasons to be fearful

Merryn Somerset-Webb was also on recession watch.

- She’s hosting a series of talks at the Edinburgh Fringe this month and has been asking her guests what they would invest in now.

She noted that:

- Value stocks are at a 44-year low versus growth stocks

- The pound is at a 35-year low against the dollar

- US stocks are a 50-year high against GDP

- Bond yields are negative

- We seem to have a new Cold War between China and the US

Money printing is likely to be part of the government / central bank solution, but her guests have not been convinced by the idea of time-limited MMT / People’s QE, preferring Milton Friedman’s insight:

Nothing is so permanent as a temporary government programme.

Almost every panellist has recommended gold, and many have also said silver, which is at a 30-year low relative to gold.

- UK assets are also seen as cheap, especially if the pound falls further in advance of Brexit.

James Ferguson also tipped oil, since production levels are at “extreme lows”.

Crisis of faith

The Economist wrote that the onset of a downturn is a matter of mood.

- They pointed out that recessions can happen without market crashes, and that many economists think that recessions need not happen at all.

A recession is defined as two consecutive quarters of contraction, and model models of how they start include a random “shock” which knocks things off course.

- This could be a market crash, a jump in the oil price, a jump in interest rates or an austerity budget.

This is held to cause people to reconsider investment plans, but the precise mechanisms are not clear or reliable.

Recessions, then, are not just the after-effects of shocks, but periods when people and firms fail to use valuable resources as they become available.

As demand slackens, bargains bloom in the form of cut-rate goods, willing and available workers, and appealingly priced assets.

We’re back to Keynes’ “animal spirits” here.

- The newspaper looks to governments and central banks to signal their resolve to keep expansions going.

But with low interest rates constraining action, and Trump seemingly not entirely clear on the outcome he wants, that makes things tricky at the moment.

What are companies for?

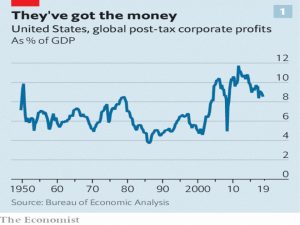

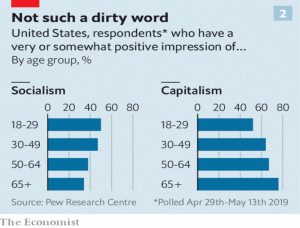

The Economist also had two articles (1 and 2) on corporate purpose.

- A bunch of US execs from the Business Roundtable have expressed the view that a wider social purpose than the current focus on shareholder value is needed.

Additional stakeholders would include workers and customers, suppliers and local communities.

- New targets would include the usual ESG suspects.

I can’t say that I find any of this persuasive.

- I’m not arguing for monopolies, cronyism, or the ignoring of negative externalities, simply for free markets that will find the best way to solve a problem.

The biggest issue in corporate governance remains the agency problem.

- That is, how to convince the hired hand managers to act in the best interests of the true owners, the shareholders.

If a new standard emerges, it’s easy to see capital flowing to firms in countries which do not adopt it.

- But if it is enforced everywhere, what will we invest in then?

The danger is that if returns (and hence maximum efficiency) are no longer paramount, firms will be accountable simply to the pressure groups who shout loudest on social media.

- So let’s hope that this is simply another pile of virtue-signalling.

For once, the Economist agrees with me:

This new form of collective capitalism will end up doing more harm than good. It risks entrenching a class of unaccountable CEO s who lack legitimacy.

And it is a threat to long-term prosperity, which is the basic condition for capitalism to succeed.

Japanification

Buttonwood wondered whether the Japanification of the bond markets was a passing phase or a permanent state.

He thinks it is not permanent:

If the economy lacks demand, governments can help to fill it by borrowing cheaply to cut taxes and raise spending. The politics are not there yet, but the Japanification of bond markets will move things along.

But this might take quite a while.

Old vs young

In the Times, Greg Hurst reported that contrary to popular belief, older people are getting less for their taxes than did previous generations.

- Older people are working longer and paying more tax on their workplace pensions.

For all cohorts, people of working age pay in more than they receive in benefits.

- This pattern reverses when people hit state pension age.

Those currently aged 20-24 receive £4.1K pa more than they pay in.

- In contrast, those now in their sixties paid in £2.6K pa more than they received when they were aged 20-24.

Those currently aged 25-34 pay in £1.1K, much less than the £3K paid in 40 years go by those now in their sixties.

Current retirees draw just £8.2K, compared with £11K ten years ago, and £12.4K twenty years ago,

SIPP charges

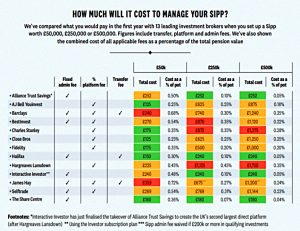

For FT Adviser, Amy Austin reported on a Which study of SIPP charges.

- The study looked at first-year charges across 13 providers.

HL was the most expensive for large posts (> £500K).

Fixed-fee providers such as The Share Centre, Interactive Investor, Halifax and Alliance Trust Savings were the most cost-effective for larger pots.

It looks as though the study focused on OIECs rather than ETFs, which makes it of limited use.

- For example, a £500K ETF SIPP with AJ Bell might cost £600 in year one (less than the £875 quoted for OIECs) but the year two cost would be just £100 – lower than any of the Year 1 costs.

Quick links

I have just three for you this week, the first two from Alpha Architect:

- They looked at how Structured Notes exploit retail investors,

- and gave the first half of their approach to Crisis-Proofing A Portfolio.

- Meanwhile, Pragmatic Capitalism looked at Black Hole Monetary Economics.

Until next time.