Weekly Roundup, 13th July 2020

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup with a look at what has worked in 2020.

What has worked in 2020?

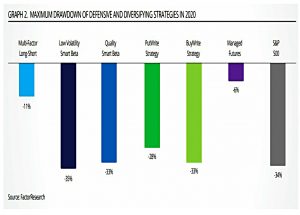

For ETFstream, Nicolas Rabener looked at which defensive and diversifying strategies have worked in 2020.

A defensive long-only strategy is one that allows investors to achieve index-like returns with less volatility. Additionally, many defensive products highlight their ability to experience smaller drawdowns.

Bonds are the historical defensive asset, but they now have such low expected returns that holding a significant allocation is problematic.

- PE and real estate are also widely used, but as we know, these are really Equity Alts (their returns are quietly closely correlated to equities).

Other options include quality and low volatility in the equity space (plus obviously trend/momentum) and asset classes like hedge funds.

Nicolas looked only at strategies with academic support:

- Multi-factor long-short investing: Beta-neutral long-short portfolios, which provide

exposure to a variety of factors like value, momentum, or quality. - Low volatility smart beta: A long-only portfolio of low-risk stocks.

- Quality smart beta: A long-only portfolio of high-quality stocks, which are typically

defined as companies with low leverage and high profit margins. - PutWrite strategy: Employs a covered call approach that buys the S&P 500 and sells

at-the-money calls on the index. - BuyWrite strategy: Sells at-the-money S&P 500 puts and invests the cash in short-term Treasuries.

- Managed Futures: Trend-following across all asset classes, which includes long and

short positions in futures.

He classes long-short and trend as true diversifiers, and the others as defensive strategies.

In mid-May (when Nicolas carried out his analysis), only managed futures had positive returns for the year.

- Long-short was consistently negative, as it relies on the value factor.

The defensive strategies were all similar to the S&P 500, which is not surprising as they are all long-only.

- The poor performance of low volatility (due to beta compression, or indiscriminate selling) is particularly disappointing, as it performed much better during the 2008 crash.

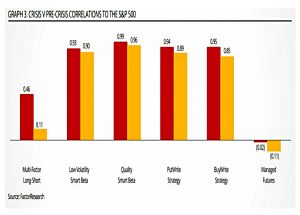

Correlations notoriously spike during crashes.

- The long-only defensive strategies remained highly correlated to the S&P 500.

The increased correlation of the long-short portfolio is explained by sector differences (cheap retail vs expensive tech), which won’t get corrected until the next rebalancing point.

- This could be as long as a month away, which leads to an increase in beta from neutral during a rapid crash such as this.

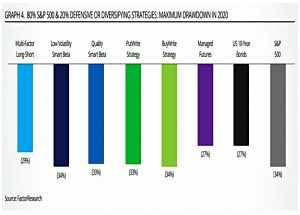

Looking at 80/20 portfolios (20% defensive) shows that trend made the most impact, though no greater than a bond allocation would have.

- As usual, my default approach would be to hold a little of everything, but if your focus is purely on the crisis alpha, trend (and bonds) would seem to be the way to go.

Market Timing

In the FT, Terry Smith was having a go at market timing.

- Regular readers will know that I’m a fan of Terry, but also a fan of certain versions of market timing.

We recently started a series of articles on this topic.

Terry does not agree:

When it comes to so-called market timing there are only two sorts of people: those who can’t do it, and those who know they can’t do it.

Of course, he’s party talking his own book (( Another “advertorial” column from the FT )) in that he runs a massive long-only equity fund and he doesn’t want his investors selling out in panic during every market crash.

- And in another sense, what Terry does (buying a select few “quality compounders”) is as close to market timing (or stock timing) as it is to passive index tradcing.

But Terry is right that most people talk about market timing in terms of selling their stocks before a crash, whereas in practice, selling by retail investors goes up after a crash.

In order to successfully implement market timing you not only have to be able to predict events — interest rate rises, wars, oil price shocks, the impact of the coronavirus, the outcome of elections and referendums — you also need to know what the market was expecting, how it will react and get your timing right.

In terms of “light-switch”, long-only, in-out stock investing, he is correct.

- And then, of course, you have to decide when to get back in again.

But as Nicolas showed above, there are defensive strategies available, and the best of them (long-short and trend) involve something that looks a lot like market timing.

Significance

On the Enterprising Investor blog from the CFA Institute, Joachim Klement looked at the cult of statistical significance.

- The title of his article is also the name of a book by Stephen T. Ziliak and Deirdre N. McCloskey.

The idea behind the book is that finance and economics (and social sciences generally, from memory) are obsessed with “significance” at the 5% probability level.

- Of course, such results will be found by chance for one in every 20 experiments or tests.

As Big Data has emerged in recent decades (or rather, the ability to quickly and cheaply process Big Data), researchers have become more likely to find spuriously significant patterns.

We can detect smaller and smaller effects that may or may not be economically meaningful.

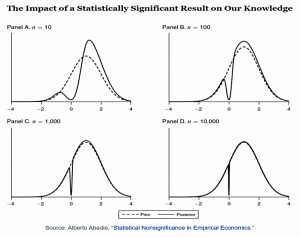

Joachim looks at a paper called “Statistical Nonsignificance in Empirical Economics” by Alberto Abadie, which looks at the amount of knowledge added by a statistically significant test result.

In the charts, the dotted line is the assumed normal distribution and the solid line is the likely distribution given a result with 5% probability.

- The greater the number of data points, the less change that we can assume in the distribution.

On the other hand, if there’s a failure of statistical significance with a test on 10,000 data points, we learn an awful lot.

Joachim thinks that this is why most equity factors are hard to make money from.

- He only trusts value momentum and “a really esoteric factor that I still haven’t understood properly”.

Annoyingly, he doesn’t tell us what that third winning factor is called.

Currency volatility

Buttonwood looked at why zero interest rates could lead to currency volatility.

- In a nutshell, if interest rates are unable to adjust to economic problems, something else must.

You might expect the opposite: shifts in interest rates (or changes in expectations about future rate moves) are big drivers of FX rates.

To explain why FX rates would move in the absence of interest rate moves, Buttonwood matches trade and capital flows:

Say a country runs a current-account deficit worth $10bn each year. To fund this, it borrows $10bn from abroad. The higher its short-term interest rates compared with other countries, the more it attracts such funds.

Alternative funding options include selling assets to foreigners.

- In this scenario, the FX rate is the level of the currency which balances the current and capital accounts.

Say a country which exports both goods and raw materials runs into lower demand for commodities.

- Its FX rate would fall, making its goods cheaper and more attractive.

Normally, the central bank would also cut interest rates to stimulate domestic spending to compensate for the lost money from raw material exports.

- If rates are already at zero, the FX rate has to change more, to make up all of the shortfall.

Fiscal stimulus (government spending) is another possible tactic, but unless the timing is perfect, this could also add to currency volatility.

Put simply, if you lack the sort of assets—and growth story—that foreigners can buy into, your currency is at more risk in a zero-rate world.

AIM

In the run-up to the Summer Budget last week, a few people rushed to the defence of AIM, worried that the IHT relief which props up the best shares on the junior market might be about to be withdrawn.

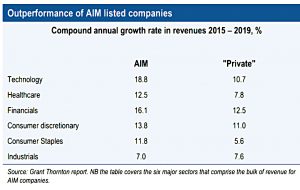

Equity Development quoted a Grant Thornton report:

Small companies listed on AIM perform ‘better’ – generating more added value, more employment and far greater tax receipts for HMRC – than comparable “private” companies.

In their own report, they calculated that for the c. £50M pa that IHT relief costs, AIM firms have added £4.7 bn pa to the UK economy, and resulted in payments of more than £1 bn pas to HMRC over the last five years.

VCT

In the FT, Andy Bounds reported on calls from the Venture Capital Trust Association for the government to relax state-aid rules which limit investments in startups.

- The VCTA includes 10 of the largest VCT managers, comprising 75% of the industry (£3,3bn in assets, 80K employees, £16 bn pa in sales).

This change would allow VCTs to invest £500M in small businesses, saving thousands of jobs.

- Many of these firms are loss-making, which means they can’t access other forms of government support during the pandemic, such as loans.

At the moment, a company cannot qualify for VCT funding if it is more than seven years since it made its first sale, or in the case of companies designated as “knowledge intensive”, it is more than 10 years since annual revenue passed £200,000.

It cannot have more than 250 employees, gross assets of more than £15m, or have received more than £5m of funding in the past 12 months or £12m of VCT funding over its lifetime.

It doesn’t sound like the Treasury is interested, though (as the Summer budget would seem to indicate):

[The UK support package for startups] is one of the most generous in the world. We will continue to engage with stakeholders on our various new support schemes to ensure they are as effective as possible.

Quick links

I have six for you this week:

- Alpha Architect looked at the Overnight Anomaly

- And asked whether Treasuries have a place in a modern portfolio

- The Economist looked at the present-day Space Race

- And warned that the ongoing economic recoveries could easily go wrong

- UK Value Investor explained why Ted Baker has been both a disaster and a gift

- And Flirting with Models looked at hedging.

Until next time.