Weekly Roundup, 21st January 2019

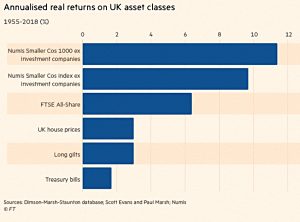

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, where Kate Beioley was looking at the returns on UK asset classes.

Contents

Returns on UK assets

It’s a thinnish Roundup this week, with most of the press occupied by Brexit shenanigans.

The research comes from the London Business School (via Numis), and covers the period from 1955 to 2018.

- Small stocks beat large stocks which beat houses and gilts, which beat “Treasury bills” (( I’m not sure how a UK private investor can access these )).

So no surprises.

In the chart above, the Smaller Companies index tracks the bottom 10% of the UK market (by value), and the Small Companies 1000 tracks the bottom 2%.

- These are annualised real returns, so they are quite chunky, even for the FTSE All-Share.

It should be noted that costs, taxes and rental income are excluded from the calculations (as is the hassle of being a landlord).

- But we should also remember that future returns will not necessarily match those of the past, particularly in the case of property, which is at record highs compared to incomes and rents.

An 8% pa, after-tax net rental yield would bring property up to the level of the smallest companies.

- And if anything approaching that were available, I would be much more interested in property investing.

The gross, pre-tax rental yield on my home is around 3% pa.

- The net, after-tax yield would be around 1.5% pa.

I can get that in a Marcus instant access account.

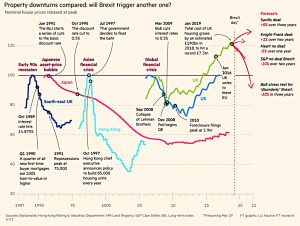

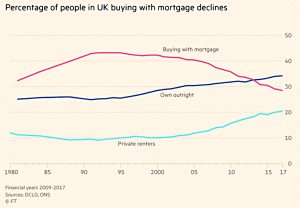

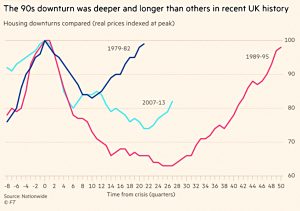

UK house prices

Nathan Brooker looked at previous housing market crashes, to see if we can expect another one in the UK following Brexit.

They looked at:

The UK recession of the early 1990s, the Japanese asset price bubble, the Asian financial crisis and the global financial crisis of 2008.

The consensus was that things won’t be like 1991 (too few mortgages these days, tougher lending criteria, no inflation and better reactions from policy makers).

The US housing crisis after 2008 was caused by sub-prime lending, which is uncommon in the UK.

- The corresponding UK recession resulted from exposure to the US economy which had already been forced into recession.

An Asian recovery – as seen in Hong Kong and Singapore in the decades after the crisis of 1997 – is also ruled out by the FT.

- It was driven by the emergence of China, which even a Britain freed from EU red tape would be unable to rely upon.

So the newspaper reasons that the most likely scenario is Japan, whose house price crash has so far lasted 28 years.

A price crash, a stagnant market, an ageing population and low interest rates.

So says Neal Hudson, director at Residential Analysts.

I can’t see it myself – the population is rising, household sizes are shrinking and enough houses aren’t being built.

- We need interest rate rises and inflation to give the housing market lasting problems, and Brexit isn’t going to cause those.

Perma bear

In the Economist, Buttonwood caught up with Societe General’s Albert Edwards – a perma-bear for more than two decades – at his annual conference in London.

At this week’s bear-fest he scoffed at the confidence central bankers have expressed in their ability to reverse QE.

I must admit that I have a few doubts about that myself.

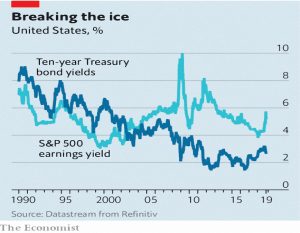

Edwards is famous for his “Ice Age” thesis, based on Japan from the 1990s:

Debt and disinflation would lead to rising bond prices (and falling yields).

At the same time, there would be a “derating” of equities, so that prices would fall relative to earnings (and the earnings yield would rise).

Bond yields have fallen, but QE has managed to hold off the derating of equities.

Now that QE is being withdrawn, Edwards expects a deep recession in the US (based on the high level of corporate debt).

The risks of a hard landing in China have not abated. And the euro is doomed to break up – younger Italians are far more hostile to the European Union than older ones.

He thinks that “fat-cat QE” will be replaced by the “People’s QE” favoured by Corbyn.

When recession bites, “Corbyn will be seen as a moderate!”

Edwards recommends that investors protect themselves with cash and gold.

- He expects the yields on US Treasuries to go negative, which means that prices will rise still further.

- But bonds will then suffer when the authorities are able to stoke inflation (inflation hedges in general are therefore a good idea).

- Japan is the safest equity market – it has cheapish, profitable firms with lower debt.

It’s all a bit Chicken Little for me, but it’s worth reading between the lines for the direction of travel.

Borrowing too much

The newspaper also had an article about the increased tolerance of economists in general for higher government borrowing.

- They have been surprisingly positive about Democrat plans to abandon PAYGO rules which mean that new spending has to be funding by equivalent cuts or tax increases.

“Modern Monetary Theory” (MMT) is now popular on the left in an era where low interest rates make government borrowing look less scary.

- Japan has debts equal to 230% of GDP, but can still raise money in its own currency.

The idea that safe lending to the government would reduce productive investment has been replaced by the idea the government should do the spending (on infrastructure).

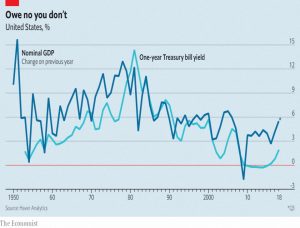

Traditionally, safe government borrowing requires that the rate of GDP growth exceeds the interest rate on the debt, so that the debt shrinks over time.

- This is a low bar at the moment, but growth tends to be higher than the interest rate.

- Since 1870 the US 1-year bond interest rate has averaged 4.6%, whilst GDP growth has averaged 5.3% pa.

The 1980s was the only troublesome post-war decade.

This doesn’t mean that government borrowing has no limits:

Whether or not creditors mind, a government can throw only so much cash at its citizens before their spending exhausts the economy’s productive capacity and pushes up prices at an accelerating pace.

And in the end, creditors do mind, and so do the FX markets.

- The tipping point is not easy to identify in advance, but this way lies Venezuela.

St James Place

Justin Case had an interesting piece in Money Marketing about a new client testimonial video from St James Place, who have the reputation of being the most expensive advisers / platform / wealth managers in the UK.

- I’ve heard tales of 5% up front and more than 2% per year.

According to Justin:

It reveals a host of home truths about where the perception of not just SJP but the advice profession as a whole falls down in the eyes of the public.

The happy clients don’t tell you much about what SJP do:

There is little to no detail whatsoever about what the advice process actually involves, what the proposition SJP offers actually is, or even an easily-identifiable unique selling point. There isn’t much emphasis on investment performance.

What the clients do tell you is what it feels like to be a client of SJP and the emotional value they get from their adviser. The advisers are pitched as doing what is best for the client, not themselves.

SJP client Maggie was very happy her adviser was “not trying to sell me something”. But SJP has in fact operated a “Nectar points” style system where advisers are rewarded on elements including assets and revenue generation.

This reminds me of the discussion at the Boring Money conference last year:

- The formula for trust is competence + benevolence

- Doctors score highly, but finance people score low on benevolence

So the key to success in finance is more touchy-feely messaging to appear benevolent.

- That SJP can overcome their cost disadvantage through soft skills is both impressive and depressing.

HL are a similar case, though less expensive than SJP.

- Investors just don’t seem to care about high costs, so I guess we are stuck with them.

Here’s a quote from one of the SJP clients:

I didn’t go to them because I wanted the cheapest product. I went to them because I wanted the best service I could get. For as long as I receive the service and SJP performance then the payment is a secondary consideration.

If you’re interested, here’s the video – I promise this is not an affiliate link!

Meetup

I’ve taken over the organisation of a Meetup group that was about to be closed.

- It’s called London Passive Investing Club, and has 365 members as a I write.

If you can get into London, and want to learn more about Passive Investing, please think about joining the group – you can do that here.

- Please also take our survey, so that we know in which direction to take the group in the future.

If people want the group to continue, then in due course I’ll set up a parallel group about Active Investing.

- But given my previous (lack of) success in getting groups going, that could be a long shot.

Quick links

I only have six for you this week:

- Enterprising Investor explained that Best does not mean Optimal,

- Larry Swedroe looked at whether the Bucket approach destroys wealth,

- Dual Momentum came back at last week’s post from Flirting with Models about momentum’s fragility,

- The Economist asked whether Google is an evil genius,

- The IT Investor tooks some positives from 2018, and

- UK Value Investor explained why he’s sold Glaxo despite the 5% yield.

Until next time.