Weekly Roundup, 23rd October 2018

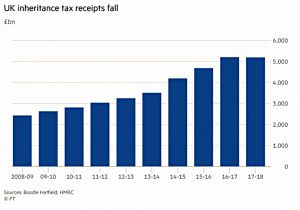

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with the Chart That Tells A Story. This week it was about IHT receipts.

Contents

IHT receipts

Lucy Warwick-Ching reported that IHT receipts are down for the first time in a decade.

- They are still double what they were in 2008/09, at £5.18 bn during 2017-18.

The plausible interpretation is that the lack of indexation of the IHT allowance (£325K since 2009) during a boom in stock markets and (until recently) property prices has pushed up returns.

The recent plateauing would be down to the slowing of the property price rise and the introduction of the residence nil-rate band (£100K in the last tax year).

- This applies only to people passing their house to their children, but will have made some difference.

Lucy speculates whether there will be changes to IHT in the forthcoming Budget, but we’ll look at that in detail next week.

- I think the IHT allowance is shockingly low (its $5M in the US), but any tax that is only paid by 5% of households will always be a target.

Drip-feed investing

Tim Harford looked at drip-feed investing.

- This strategy (known in the US as dollar cost averaging) feels sensible, and it does provide some psychological comfort when the sums being invested are large in comparison to your existing portfolio.

But in upward-trending markets – like stocks – it will usually produce lower returns than lumps-um investing.

- We looked at this in detail a few years ago in The Best Time to Start is Now.

Tim makes the useful point that a better way than drip-feeding to reduce your risk (and consequent nervousness) is to hold some money back from the markets entirely.

- In other words, make sure that your asset allocation matches your risk tolerance.

Drip feeding also acts against the general tendency to invest when markets are high and sell when they are low.

- So for some people, it can be the least-worst option.

Tim quotes Greg Davies of Oxford Risk:

Cost averaging is deliberately doing something slightly inferior, to prevent the likelihood of something very inferior.

Tim suggests a couple of other heuristics, which I support:

- If it takes less than two minutes, do it immediately.

- Never drink alone.

Value investing

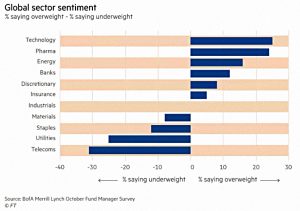

Michael Mackenzie looked at whether it was time to buy value rather than growth.

- Growth – especially tech – has outperformed since 2009.

But now long-term bond yields are rising (in the US, at least).

- This increases discount rates and reduces the present value of future cash flows from growth.

Michael notes that a serious shift away from tech would also hurt Wall Street, which has outperformed the rest of the world on its coat tails.

But he sees lots of macro threats to a value resurgence.

- Perhaps best to wait for signs of resolution in China, Italy and Brexit.

At the same time, things are starting to look a little bit like 2000.

Cash

Moira O’Neill warned investors not to have too much cash.

- Of course, as we know, cash is a terrible long-term investment.

It rarely keeps pace with inflation.

Moira recommends six months of cash in accumulation, and two years in retirement.

- I usually hold four years’ worth in decumulation, but I have even more at the moment.

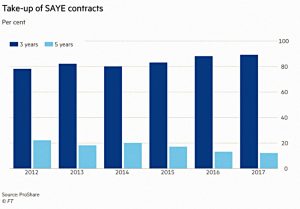

Lindsay Cook looked at share incentive schemes.

- Save As You Earn (SAYE) was launched by Margaret Thatcher in 1980 – this allowed employees to buy shares at a discount.

- Gordon Brown’s Share Incentive Plans (SIPs with one P) from 2000 allowed employers to give away free shares.

The schemes require a lock-in of three or five years, which puts off millennials, who don’t expect to stay in their present jobs for five years.

- The chart shows how the proportion of shorter contracts has been increasing.

Since there is no interest paid on SAYE as the cash builds up, the contributions are eroded by inflation until the purchase of the shares at the end of the contract.

- If the share price falls during the contract, employees are not forced to buy – they are effectively saving for a six-month option to purchase at a pre-agreed price.

- You have to still be an employee of the company to trigger the purchase.

Gains on sales of shares are not exempt from CGT.

- But hanging on the shares is not advisable either, since employees already have a significant investment in their employer’s future.

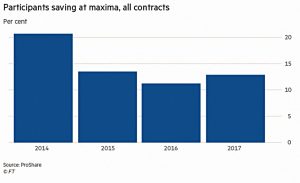

The maximum annual saving into SAYE is £500 per month (£6K pa – a decent sum).

- Only 4.5% of employees do this, and the average saving is £118 per month (£1,400 pa).

Stablecoins

The Economist looked at stablecoins, a new form of crypto currency.

- “Traditional” Bitcoin is 23 times more volatile than the S&P 500 (which itself is no slouch).

- This is a big problem for people who might want to use crypto for payments, savings or lending.

Stablecoins are designed not to be volatile.

- There are more than 20 already, and though they account for less than 2% of total crypto valuations, they are involved in a much higher proportion of trades.

- More than $350M of venture-capital money has gone in to them.

Most stablecoins use fiat money, gold, or baskets of other cryptos as collateral to dampen down their price swings.

- The biggest is Tether, which uses the dollar (as does rival TrueUSD).

- Some use algorithms instead.

One drawback is that although they have attractions for legal crypto users, they are also attractive to those who want to evade tax that is often due when crypto is exchanged for fiat.

Swiss secrecy

The newspaper also reported that a recent court ruling has further reduced Swiss banking secrecy.

- A whistleblower from a Cayman Islands subsidiary of a Swiss bank was held not to be bound by Swiss secrecy laws (as they stood back in 2008, when the data was leaked).

That means he dodges a jail term of up to five years.

Central bank independence

The Economist also notes that Trump’s complaints about the Fed’s rush to raise interest rates might start an overdue debate about central bank independence.

- The logic runs that governments can’t be trusted not to print more money – it stimulates the economy and the inflation boost reduces the impact of public debt.

But they can’t stop, and so inflation consistently goes up.

- An independent central bank will not constantly print money, and will sometimes raise interest rates instead.

- Which can in turn lead to high unemployment.

The Economist thinks that some central banks (like the Fed and the ECB) are not as independent as they seem.

- And that sometimes (as in the UK in the 1970s and 1980s) inflation is defeated by government action.

- There are also problems of cause and effect, and common causality.

The Economist would like to see growth (including wage growth) added to the list of central bank targets, and it’s hard to disagree.

- The alternative will likely be more QE, and eventually, helicopter money.

Leaseholds

The newspaper also looked at leasehold reform in the UK.

- Leaseholds for houses have never made much sense, except as a nice little earner for the builder / freeholder.

- And I say this as someone who would love to own a portfolio of nice, reliable ground rents.

Leaseholds for flats, where several properties share the same land (( And the similar “flying freeholds” which are common in hilly places, like the Pennines and Cornwall )) are easier to understand.

- But even here, common ownership by all the flats involved seems the simplest approach.

The government now plans to cap ground rents at £10 a year.

- But leaseholds won’t be banned, even for houses.

Rising bond yields

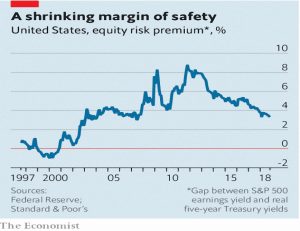

Buttonwood looked at why rising bond yields are making owners of stocks nervous.

Often, stocks and bonds are inversely correlated.

But when bond prices fall because interest rates are set to be higher, the same higher future interest rates mean that future equity returns are worth less today, and so stocks fall as well.

Buttonwood uses the earnings yield (the inverse of the PE ratio) as a proxy for real stock returns.

- This is currently 4.3% for the S&P 500, compared to a 1% yield on inflation-linked Treasuries.

- So the equity risk premium is 3.3%.

The average for the past 117 years is 4.5%, but the premium can rise above 8% when things are, well, riskier.

- During the dotcom boom, in contrast, the equity risk premium went negative.

Things are fine for now, but there is not much room for the premium to shrink further.

Quick links

I only have two for you this week:

- Musings on Markets looked at The Money In Marijuana, and

- EconLib looked at the ways in which people really Escape Poverty.

Until next time.