Weekly Roundup, 26th July 2021

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup with a look at indexing.

Contents

An index of everything

In the FT, Robin Wigglesworth reported on MSCI’s attempts to create “the ultimate index” – one tracking the performance of all markets.

Peter Shepard, head of analytics research and product development at MSCI, used to be a theoretical physicist and is wary of using the term “ultimate index”:

I need to be careful about not falling into that trap again. I think we may be able to find a grand unified theory of physics at some point, but we’re not going to be able to find a grand unified theory of markets.

The two problems with a broader index are:

- What to include, and

- Where to source reliable and current data for non-public markets.

After that, you come to relative weightings between asset classes, geographies and stock factors like (small) size.

- With bonds, in particular, using a market cap approach produces non-intuitive results (higher allocations to the largest and potentially more risky issues).

Shepard also stresses the importance of simplicity and transparency:

I could come up with a great black box, but if you don’t understand it, you won’t trust it and you won’t use it.

If MSCI can get this right, it could be very useful:

If well constructed it could form the basis of cheap but powerful investment products for everyone from retirees to sovereign wealth funds. While the cost of investing in individual asset classes has been hammered down thanks to the invention of index funds, deciding on how to mix them is often handed over to a pricey financial adviser.

Shepherd obviously agrees:

I think there’s a huge opportunity. The asset allocation decision is the most important decision for a lot of investors . . . But we’re leaving this really critical decision to people who may not be that skilled, or they turn it over to someone who charges fees.

I think that the construction of such an index (or a set of indices for different stages of the investment journey) is definitely possible.

- But from my own experience of trying to shift people away from stock/bond portfolios (or in extreme cases, property/cash portfolios) towards risk parity-style strategies, marketing these new indices will not be easy.

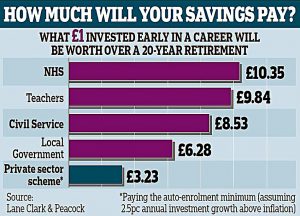

Public vs Private pensions

On ThisIsMoney, Ben Wilkinson reported on the great divide between public and private sector pensions.

- On average, private sector schemes will return just over £3 for every £1 of employee contributions.

Meanwhile, the top public sector pension (for the NHS) returns more than £10 for every £1 paid in by a worker.

One in four pensioners and 16 per cent of the working-age population are members of one of the four largest public service pension schemes. The teachers’ pension scheme is second best to the NHS as it rewards savers with nearly £10 for every £1 saved.

The data comes from Lane Clark and Peacock and looks at early-career contributions at the auto-enrolment minimum levels.

- Pension pots are assumed to grow at 2.5% pa above inflation, and workers are assumed to retire at age 68.

Tax relief and employer contributions are also included.

Public sector schemes like the NHS’s still offer pension promises linked to average career salary that provide a guaranteed rate of retirement pay which will also rise with inflation. And this means they are now far more valuable than private sector pension schemes, which are largely defined contribution.

The DC vs DB gap shows up in employer contributions:

Latest figures from the ONS show that the average employer contribution for a DC

scheme is 3.5 per cent — compared to 22.2 per cent for salary-related, or defined benefit, schemes.Teachers and school staff pay anything between 7.4 per cent and 11.7 per cent but their employer now has to pay 23.68 per cent. Those in the Civil Service scheme pay in between 4.6 per cent and 8.05 per cent, while employers are asked to pay as much as 30.3 per cent. Local government workers pay between 5.5 and 12.5 per cent, while employers contribute around 19 per cent.

PE vs ESG

In the FT, Patrick Jenkins suggested that the recent glut of private equity buyouts might be a reaction against the trend towards ESG values.

Buyout firms rightly pounce on listed companies that they deem undervalued or bloated. In so doing, they keep capitalism efficient and act as a positive reactionary force.

But is private equity also reactionary in the conservative backlash sense of the word — facilitating a rebellion against some of the progressive constraints of public company existence, particularly the growing demands of complying with standards on environmental, social and governance issues?

There’s definitely an argument to be made that PE would prefer to fix broken companies without public scrutiny – without the market seeing how the sausage is made.

There’s also the issue of executive pay, as Patrick highlights in the recent case of the Morrison’s takeover:

Fortress’s agreed £9.5bn buyout of Morrisons this month came with a strong hint that management “incentives structures” would be boosted, only weeks after the listed UK supermarket suffered a shareholder revolt over pay.

As Patrick concludes, the best way to “fix” this is to demonstrate that following ESG principles can lead to long-term outperformance.

- And that will take time.

Convertibles

Buttonwood wrote that convertible bonds are the asset class for the times.

- He says that fast-changing conditions call for flexible forms of capital.

A convertible is a bond with an option to swap for shares of common equity. Last year $159bn-worth were issued worldwide. This was around twice the value of convertibles issued in 2019. So far this year around $100bn-worth have been issued.

As well as a coupon rate of around half that of a standard bond, convertibles have a conversion rate – the number of shares that the bond can be converted into.

- This will be set so that conversion only makes sense once the share price has increased by 30-40%.

Buttonwood gives the example of a $1K bond on a $15 stock.

- A conversion rate of 50 would set breakeven at $20 per share – an increase of 33%.

Convertibles work well for startups in capital intensive businesses (eg. Tesla, until recently).

- Founders prefer not to issue equity that would dilute their own holding, but issuing debt would be expensive as there is significant default risk.

Convertibles make the debt cheap and ensure that equity is issued at a much higher price.

But old-economy cyclical firms are issuers, too. Some, like Carnival Cruises and Southwest Airlines, used convertibles last year to raise “rescue” finance at lower interest rates and without immediate dilution. Others are using them to finance investment: Ford Motor sold $2bn of convertible bonds in March, for instance.

The threat of rising inflation and interest rates also makes regular bonds harder to issue, and hence make convertibles more attractive. As Dylan Grice from Calderwood Capital explains:

[Convertibles are] nominal assets which come with an embedded call option on a real asset.

Tapering

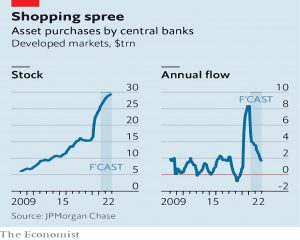

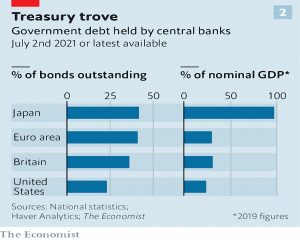

The Economist also looked at how central banks might taper their QE without causing another tantrum, as in 2013 (when bonds sold off, the dollar soared and capital left the emerging markets).

Rich-world central banks’ balance-sheets will have grown by $11.7trn during 2020-21. By the end of this year their combined size will be $28trn—about three-quarters of the market capitalisation of the S&P 500 index.

But the buying is about to stop.

- The Bank of Canada began curtailing the pace of its bond-buying in April.

- The Reserve Bank of Australia said on July 6th that it would begin tapering its purchases in September.

- The Bank of England is approaching its £895bn ($1.2trn) asset-purchase target and looks likely to stop QE once that is reached.

- In May the Reserve Bank of New Zealand said it would not make all of the NZ$100bn ($70bn) asset purchases it had planned to.

- And the European Central Bank is debating how to wind down its pandemic-related scheme.

Which leaves the Fed.

The problem with tapering is that it acts as a signal that interest rates will be raised.

The implication is that you can reverse QE without much fuss if you sever the perceived link between asset purchases and interest-rate decisions.

But this could be difficult if inflation is rising and markets are booming.

[And] if interest rates rose, however, central banks’ enormous balance-sheets could become lossmaking, [with] sizeable consequences for the public finances.

A 1% rise in interest rates will produce a bill equal to 0.5% of GDP in the UK.

Crypto

The UK’s war on crypto continues with the news that the FCA will spend £11M on a digital marketing campaign to warn people about the dangers of investing in crypto.

- The fund was announced as part of the FCA’s business plan earlier this month.

Nikhil Rathi, the FCA CEO, said:

More people are seeing investment as entertainment. This is a category of consumer that we are not used to engaging with: 18 to 30-year-olds more likely to be drawn in by social media. That’s why we are [spending £11M] to warn them of the risks.

Quick Links

I have just four for you this week, the first two from The Economist:

- The newspaper looked at Netflix’s ambitious third act

- And noted that technology unicorns are growing at a record clip.

- Musing on Markets looked at the Zomato IPO

- And Pragmatic Capitalism was learning from bad inflation takes.

Until next time.