Weekly Roundup, 28th February 2017

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with the Chart That Tells A Story. This week it was about UK bank shares.

Contents

Lucy Warwick-Ching looked at the rise in the price of bank shares over the past six months.

I have a couple of problems with this chart.

- Six months is a very short period of time in the stock market.

- There are no comparators – most shares have been rising over the past six months, and I’d like to see what’s happened to some other sectors.

Lucy says that the bank shares are picking up because the fines from the 2008 financial crisis are becoming less frequent, and no new scandals are emerging.

- The UK economy has coped with the Brexit vote better than a lot of people expected.

- This means that more people are in work and able to service their loans, so fears of defaults have not materialised so far.

- And the election of Trump means that it’s likely that we’ve seen the peak of bank regulation.

Some observers also think that the threat of inflation will cap consumer confidence and therefore any required rise in interest rates.

- Since higher interest rates would likely lead to more loan defaults, this could be good for banks, too.

On the other hand, when interest rates finally go back to normal, so will banks’ profit margins.

Personally I’m not so keen on banks as investments.

- People like them because they have high-street visibility and the big four have been around for a lifetime.

- But they are difficult to value, subject to a lot of regulation and subject to sudden lurches in direction.

I think there are better sectors to pursue.

DB pensions green paper

Josephine Cumbo looked at the government green paper on final salary pensions.

- There are still 11M members of 6,000 remaining DB pension schemes in the UK.

The big suggestion is that “stressed” employers could switch pension indexation from RPI to the lower CPI.

- This could save £90 bn, which of course has to come from the members’ pensions.

- The average pensioner would lose around £20K over their lifetime.

The most underfunded schemes might be allowed to temporarily suspend indexation.

The alternative – in the extreme – is that the pension scheme goes bust and transfers to the pension protection fund.

- This leads to an immediate 10% cut in pension for any member not already receiving funds.

We’re still a long way from this becoming law.

- Theres’s a consultation until May, then a white paper after that.

Pension transfer values

Sticking with DB pensions, over in MoneyWeek, Merryn reminded us about the high transfer values on offer.

- I looked at this a few weeks ago and decided that even 35 times the pension wasn’t worth it to me.

- That would still mean I had to earn an index-linked 2.9% pa on the cash for the rest of my life.

- And I like the diversification offered by having part of my portfolio in this low-risk, bond-like asset.

But Merryn’s article this week reminded me of another reason:

- Despite the transfer values being 35 times the annual payment at the moment, in the lifetime allowance (LTA) calculations DB pensions only attract a multiple of 20

So if you did transfer a big DB pension into your SIPP, you run a serious risk of ending up over the LTA.

- A £20K pa DB pension would convert from being valued at £400K to a pot of £700K

First world problems, but worth thinking about.

Innovative finance ISAs

Aime Williams reported that P2P lending platforms have been complaining about the UK regulator.

- The Innovative Finance ISA was launched back in July 2015, but there are no products on the market.

- The FCA said last year that it had been swamped by applications, and in the event, none were approved in time for the new tax year (April 2016).

This time around, the big platforms – Zopa, Funding Circle and RateSetter share 60% of the market – are still waiting.

- LandBay and Lending Works – which have 0.6% of the UK market between them – are the only two IF-ISAs approved so far.

I’m not holding my breath for the IF-ISA myself.

- Having to put your whole ISA allowance (£20K from April) on a single platform makes it unattractive to me.

- I prefer the investment trusts that lend in this area.

- You can find a list of these here.

Closet trackers

Chris Newlands looked at a list published by Better Finance of 165 investment funds – from 80 asset management groups – that it claims are benchmark huggers.

- You can check your funds here (it’s a separate website, for some reason)

In 2016, Esma (the European markets regulator) found that 400 out of 2,600 funds it looked at were closet trackers.

- But instead of naming them, Esma referred the findings to national regulators.

- Fidelity, JP Morgan, Schroders and Henderson all appear on the Better Finance list.

The definition used for closet tracking was active share below 60% and tracking error of less than 4%.

- The FCA found last year that £190 bn was invested in UK-regulated closet trackers.

Timing the market

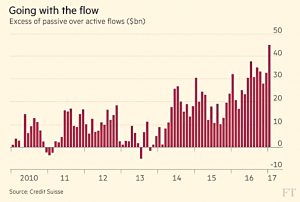

John Authers looked at market timing and the boom in passive funds.

- Is it time to get out of US stocks?

The Dow Jones industrial index recently went up for 10 days in a row, for the first time since 1987 (before Black Monday).

- Judged on PE, the US market has only ever been more expensive in 1929 and 2000

- Even compared with very expensive bonds, US stocks don’t look much cheaper

John references the research by Javier Estrada (amongst others) which shows that successful market timing can be very profitable:

- Missing the best 10 days in 40 years costs investors half their gains

- Missing the worst 10 days led to two and a half times the profit

(I have to say that for me, the lesson from that is to remain invested.)

The big problem is that timing the market is hard.

- Dimson, Marsh and Staunton found that buy and hold beat market timing on PE in 20 countries

- And many studies have shown that investors do worse than the funds they invest in, because they buy high and sell low

Consumer research group Dalbar have been looking at active and passive funds.

- Over the past 15 years investors in active funds have earned 4.0% pa, compared with 2.9% for passive funds (and 5.0% for buy and hold in the S&P 500)

- It seems that passive fund buyers are worse at market timing than active fund holders

It’s also the case that active funds hold some cash while passive funds don’t.

- So an investor switching to passive is actually causing more stocks to be bought.

Coupled with their poor timing, this means that passive investors help perpetuate booms and also contribute to busts.

John thinks that the liquidity offered by ETFs encourages passive investors to over-trade.

- And since passive funds (in the US) are largely sold by fee-based advisors, there is an incentive to churn client’s portfolios to justify the fee.

I don’t think we’ve reached that stage over here yet.

John is in favour of auto-rebalancing (as offered by many robo-advisors at the moment).

- This automatically sells high and buys low

He would still be in the US market right now, but at the minimum allocation permitted by your model.

- He notes that in 1987, the market went up for another seven months – and by another 30% – after the record streak of 10 up days in a row.

Business rates

The Economist looked at the changes to business rates that will come into force on 1st April.

- Business rates are like council tax for companies, and raise £26 bn a year (5% of all tax revenue)

They are charged against property values and are supposed to be recalculated every five years.

- But this will be the first review since 2010 and property values have increased dramatically since then, particularly in London.

Many London businesses face 100% increases, though these will be phased in (with a cap at 42% in the first year).

Since the rates don’t take into account profits, they hit small retailers the hardest.

- Large firms can supply their shops from out of town warehouses

And if you are renting, you’re being taxed on an asset that you don’t own.

I’m not keen on the changes. The secondary shopping street close to my house remains dominated by small retailers, but the chains are slowly moving in.

- We should have some kind of discount for businesses that own less than say five shops.

Tech bubble

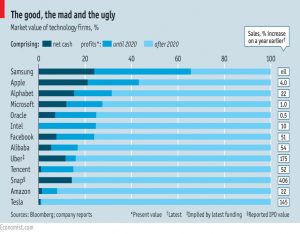

Schumpeter looked at whether tech firms are in a bubble.

- House prices in San Francisco are rising faster than in New York, and by a bigger margin than during the dot com bubble.

- Tech firms trade on the highest price to sales ratio since that time.

Schumpeter suggests three sanity tests.

The first test is cashflow, which they pass.

- In 2001 half of listed tech firms could not convert sales into cash

- In the last 12 months, the largest 150 tech firms generated $350 bn of cash flow (after capex)

The second test is whether investors differentiate between companies (in a bubble, all boats rise).

There are three types of tech firm:

- Mature and profitable (Apple, Samsung)

- Growing at more than 20%, with high margins (Alibaba, Tencent, Facebook, Google / Alphabet)

- Blue-sky – explosive sales growth but no profits (Uber, Snap)

To compare categories, Schumpeter worked out the “duration” of the firms – how much of their current market worth depends on cash, and on near-term and far-term projected profits.

- Samsung and Apple have 40% of their value in cash and near-term profits

- Tesla has more than 90% of its value beyond 2020

This is good news again – the highest valuations are on smallish firms growing very quickly.

The third test is based on the fallacy of composition.

- All these firms are assumed to have bright futures, but could they all succeed together?

- During the dot com boom, projected market shares regularly totalled more than 100%.

- And in the subprime crisis, all the banks said that other banks were holding the risks.

The aggregate profits of the big five tech firms are currently 6% of US profits.

- By 2025 this share is projected to be 10% – bullish but not impossible.

- And there is little double counting – Google doesn’t expect to dominate social media and Facebook doesn’t expect to take over search.

So in aggregate, tech doesn’t appear to be in a bubble.

Schumpeter cautions against the privately held unicorns with valuations over $1bn.

- The total value of such firms is now $350bn.

Schumpeter also worries about Amazon.

- It’s valued at $410bn, of which a third is the profitable cloud supplier, AWS.

- But 92% of its value is from projected profits beyond 2020.

- And the rest of the firm is barely profitable at the moment.

- Nor is it growing very quickly.

To justify its valuation, by 2025 it needs to be the most profitable firm in the US.

The other worry is more regulation:

- the top ten firms have turned each dollar of investment into $8 of valuation

- for Snap the figure is $36

Where are the new entrants to compete this away?

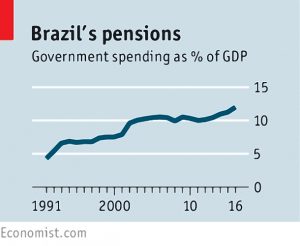

Brazilian pensions

The Economist also looked at the Brazilian pension system, which is one of the most generous in the world.

- The average Brazilian retires at 58, compared with 66 in the US and 72 in Mexico.

- Many teachers retire before 50 and widows inherit their spouses’ payments.

- The average pension is 80% of pre-retirement income, compared with the OECD average of 60%.

Pensions now make up more than half of non-interest government spending, and will hit 80% within ten years.

- Brazil spends 50% more than the OECD average on half the number of over-65s.

The president has now proposed some serious reforms:

- minimum pension age of 65

- 25 years of contributions to qualify, up from 15

- one pension per person

Surprisingly, the real has appreciated against the dollar by more than any other EM currency over the past year.

- So the markets are betting that he can get the reforms through congress.

Good luck with that.

The BBC reported – as the lead story on its front page – that insurance premiums are “set to soar“.

This sounds like a storm in a teacup to me:

- compensation payouts to injured accident victims are intended to last a lifetime

- but they are paid out as a cash lump sum up front

- to work out the size of the payout, a discount rate is used to calculate the present value of future payments

- this discount rate has been set at 2.5% pa for the past 16 years

- but the Ministry of Justice has decided that with bond yields at 1% and inflation at 1.8%, the real rate is minus 0.75%

- so future payouts will be bigger

Insurance company shares slumped on the news, but what’s the problem?

- The new rate sounds right to me – it was the old system that was nonsense.

- You haven’t been able to get a risk-free 2.5% pa after inflation for almost 10 years now.

There is a potential mismatch between short-term and long-term rates here.

- It might be better to come up with a formula based on the yield on the long bond, minus some estimate of inflation based on the spread between index-linked and non-linked bonds.

But that doesn’t mean that the old rate was correct.

Until next time.