Weekly Roundup, 7th February 2017

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with the Chart That Tells A Story. This week it was about family trusts.

Contents

Family trusts

Vanessa Houlder looked at the decline in family trusts, which have gone down in number by 27% in the last 10 years, from 220,000 to 162,000.

- Trusts date back to the crusades and are effectively a box in which you can place assets so that the income from the assets can go to a beneficiary, but the assets themselves are protected.

They have historically been used to pass wealth down through the generations, without any particular generation being able to spend the assets themselves.

- They have also historically protected against inheritance tax (IHT).

The decline is down to the steps taken by Gordon Brown to remove the protection against IHT.

- Trusts now pay 20% of IHT up front (when assets are transferred into the trust).

- And an additional 6% every 10 years.

The strange supplementary rate derives from HMRC’s idea that “a generation” equals 33 years.

- After the trust has been in existence for 33 years, it will have paid an additional 20% in tax. (( Strictly speaking, 18% will have been paid in three lumps, with the extra 2% accrued towards the next 6% payment ))

- Thus the full rate of 40% IHT will have been paid in total.

There are exemptions for assets with business property relief (farms and AIM shares), but these are exempt from IHT anyway.

- You can also make multiple transfers of £325K every seven years without paying tax.

- And there are still reasons for ex-pats and non-doms to use trusts.

By coincidence, I sat through a good presentation on the uses of trusts last week.

- I’ll come back to trusts – and their main alternative, the family investment company – in a future post.

Merryn on Trump

Also in the FT, Merryn was writing about Trump.

- She sees his election as a major turning point.

- It could mean the end of globalisation, as voters are fed up with multi-nationals, immigration, low wages and supra-national organisations (eg. the EU). (( She also said that he might be an alien, but I’ll let you read the article to find out why.

Merryn expects debt to become more expensive, both because of rising interest rates, and Trump’s plan to remove the “debt shield” – the interest deduction (more on this below).

- She also expects protectionism, and rising labour costs.

- And she says higher taxes are coming, though this will be in the form of better enforcement of lower headline rates (for corporates).

Merryn’s conclusion is that investors should get out of multinationals and head for smaller companies.

- She recommends investment trusts, specifically:

- River & Mercantile UK Micro

- Miton MicroCap Trust, and

- Aberforth Smaller Companies

All three of these appear on our Investment Trusts Master List, along with another six UK smaller companies trusts.

Digital tax revolution

HMRC published a press release about what it is calling the “digital tax revolution“.

- The Making Tax Digital project is designed to replace annual tax returns for most businesses with quarterly (online) returns.

This is not as dramatic as it sounds:

- businesses turning over more than the £83K pa VAT registration threshold already complete quarterly online VAT returns

- annual accounts and tax returns are submitted online

- and the PAYE system (salaries, NICs and income tax) requires monthly online submissions

The highlights of the press release include:

- spreadsheets can be used to records receipts and expenditure

- software will automatically generate the updates to be sent to HMRC

- software will be free for smaller businesses (not defined)

- businesses that can’t go digital (not defined) won’t have to

- charities – and those with turnover below £10K pa – won’t have to go digital

- the cash accounting basis will be extended to more businesses

- there will be no late submission penalties for the first year

The new system is planned to go live by 2020, and is expected to reduce HMRC costs and get more tax bill right first time.

- corporate tax bills are thought to be £8 bn light at the moment

Alt beta

The Economist reported on the rise of “alt beta” to stand alongside smart beta as a semi-passive investing strategy.

- Alt-beta is designed to mimic the moderate but uncorrelated returns that hedge funds provide.

- Unlike smart beta’s “buy and hold” indexing strategy, alt-bete funds go short, and use derivatives.

Buying alt-beta is much cheaper than buying a hedge fund:

- alt-beta usually costs between 0.75% and 1% pa, compared with 2% pa plus a 20% performance fee on new high water marks from hedge funds

- There is now around $70 bn invested in al-beta, compared to $3 trn in hedge funds

The article doesn’t mention any funds in particular, and I haven’t come across any here in the UK.

- If you spot one, please let me know.

US tax reform

Buttonwood looked at how Trump’s expected cuts in corporate tax rates might be paid for.

- The focus to date has been on “border-adjustment” rates – effectively part import duties and part VAT adjustments

- But an alternative could be the repeal of the interest tax deduction on debt that has stood since 1918.

This perk is worth 11% of corporate assets, and encourages companies to run high levels of debt.

- This in turn means that more companies will go bust in a recession.

- Thus the Economist is in favour of getting rid of the deduction (as am I).

This should raise 1.6% of GDP for the US government (and even more in times of higher interest rates).

- The corporate tax rate could be cut from 35% to 15%.

- In practice the headline rate will probably come down less, since some of the savings will be used to allow firms to write off capital investment in the first year (rather than amortise it).

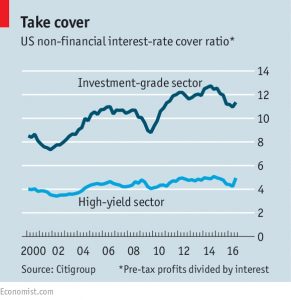

If the tax rate comes down to 20%, Citigroup have calculated that companies with an interest cover ratio (pre-tax profits divided by interest paid) of more than 2.4 would be better off in principle.

- In practice, deductions mean that the effective rate of corporation tax paid is 27% rather than 35%.

- This means that interest rate cover of more than 4 would be needed to see a benefit.

This would be bad news for companies in the junk bond sector of the market, including lots of firms owned by private equity.

It’s also not clear that the change would make the economy safer in the short run.

- If Trump stimulates growth, more investment (and borrowing) will be needed.

- And interest rates are near record lows, even if the interest is no longer tax-deductible.

There’s also the question of international harmonisation:

- US firms would be incentivised to borrow abroad, where the interest would still be deductible.

- They would probably borrow more than required, in order to retire the inefficient US bonds.

So yields on high-grade bonds would fall (and prices rise) while the opposite happens to junk bonds.

- The default rate on junk bonds could be expected to increase, as such companies would find it harder to refinance.

Basic income in India

The Economist also had a couple of articles about universal basic income (UBI) in India (1 and 2).

- We’ve discussed basic income – a monthly payment to all citizens that isn’t means-tested a few times before.

- There are no large-scale schemes in place yet, but many observers think that it will be forced upon us by robots and software automation reducing employment levels.

India has 950 central government welfare programmes, plus many more operated at state level.

- So the potential savings on red tape are substantial.

The central schemes cost 5% of GDP, and for 6% to 7% of GDP, all adults could be given $9 a month.

- This would reduce the numbers living below the poverty line from 22% to 0.5% of the population.

- Giving cash would be less susceptible to corruption than the current “welfare in kind” schemes.

- And a small trial in Madhya Pradesh has calmed fears that UBI would be wasted on booze and gambling.

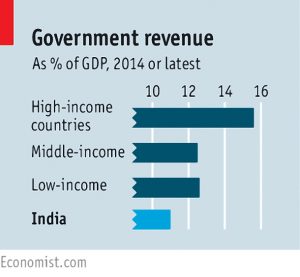

The main stumbling block is the low level of tax receipts in India – just 11% of GDP.

- The current plan hopes to reduce the cost of UBI to 5% of GDP by excluding the richest 25%

- But this depends on either a voluntary opt-out by the rich, or the flawed means-testing used within existing welfare schemes.

There’s also a lack of bank branches in rural areas.

And the recent fiasco surrounding the withdrawal of high-denomination banknotes doesn’t suggest that the Indian government would be good at managing the transition to a single welfare payment.

- So there is a risk that UBI would run alongside existing schemes.

Despite all this, UBI makes a lot more sense in India than it does in the UK.

A few links

And finally, a few of the links that I’ve tweeted out during the past week:

[contentcards url=”https://www.finalytiq.co.uk/busting-myth-u-shaped-retirement-spending/” target=”_blank”]

[contentcards url=”https://blog.thinknewfound.com/2017/02/embracing-conflict-asset-allocation/” target=”_blank”]

[contentcards url=”https://www.ftadviser.com/Articles/2017/02/02/Entire-UK-soon-to-be-heavily-reliant-on-state-pension” target=”_blank”]

[contentcards url=”https://www.ftadviser.com/mortgages/2017/02/02/older-homeowners-view-equity-release-negatively/” target=”_blank”]

Until next time.