HFEA 5 – Lifecycle Investing

Today’s post is another in our series on Leveraged ETFs.

Contents

Lifecycle Investing

We’re on a bit of a detour today.

- We’re looking at a book that isn’t directly about triple-leveraged ETFs, but which does recommend the long-term use of leverage.

The book is called “Lifecycle Investing: A New, Safe, and Audacious Way to Improve the Performance of Your Retirement Portfolio” by Ian Ayres and Barry Nalebuff.

- It came out in 2010 and the authors received hate mail for recommending the use of leverage so soon after a financial crisis whose effects had been so exacerbated by gearing.

The authors note that people are generally happy to buy houses at 10:1 or even 20:1 leverage, but are very uncomfortable with buying stocks at even 2:1 leverage.

I plan to work through the book in more detail next year, but for now, I want to see how the strategy compares to HFEA, and whether there are any lessons we can carry over to HFEA.

Time diversification

The theme of the book is that you need to be diversified across time, as well as asset classes and geographies.

Young people have most of their portfolios invested in invisible “human capital” (basically, their future earnings).

- The natural progression of their earnings and outgoings through their working life means that the majority of their retirement contributions (and stock investments) will occur later in their careers.

People make the mistake of putting 80 percent of their stock investments in just ten years. This can have disastrous consequences if those ten years happen to end badly.

People close to retirement who invested the bulk of their stock money in [a] lost decade will not have done well. You are better off spreading your stock investments across several decades.

This is the opposite of what we want since stocks benefit from compounding over long time periods, and you are vulnerable to a crash as you approach retirement.

- The fix is to use leverage when young to buy more stocks, and then tp gradually unwind this leverage as you age.

This will spread your equity timing risk over your entire working career (say forty years) rather than focusing it on ten to fifteen years at the end of your career.

Temporal risk

There are several reasons why savers delay investing:

- paying down mortgages (particularly when interest rates were higher)

- children’s education

- lower salaries at the start of their careers

The authors (I’ll refer to them as A&N from here) recommend that investors work out the present value of their future investment contributions, and get 50% of that in stocks as soon as possible.

- The idea is that you act as if you would if you had all that money today rather than in the future.

I see three issues:

- the potential for error in the size of the future contributions

- it’s not easy to predict your salary progression when you are 25 years old

- the discount rate

- this will vary through their future 40-year career, potentially throwing off the optimal allocations, though presumably still indicating the correct direction of travel

- access to the leverage needed to take an early 50% stocks position

- see the implementation section below

Rules

The two comparison portfolios used by A&N are:

- the “birthday rule”, a modified version of “your age in bonds”.

- If you are 25, your age in bonds means you have 75% stocks

- Another version of this is “100 minus your age” in stocks, which also works out at 75%

- The birthday rule is “110 minus your age in stocks” which works out at 85% (getting a bit high for me)

- For a 60-year old, the three rules work out at 40%, 40% and 50% in stocks

- A constant allocation to stocks (usually 75% in the book)

Versions of the birthday rule are used by (ironically-named) lifestyle and target-date retirement funds to produce equity glide paths before and during retirement. (( Equity glide paths are covered in detail elsewhere on the blog ))

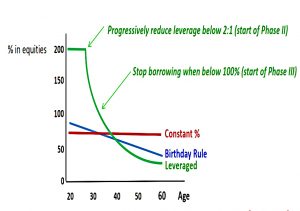

A&B also have leverage caps by age:

- a max 2:1 leverage in your 20s (Phase 1)

- reducing leverage as you approach your equity $ target (Phase 2)

- no leverage when you have more equity dollars than your target (Phase 3)

- in fact, in retirement, you are recommended to unlever further by replacing stocks with bonds (( I think this is a bad idea if you expect your retirement to last for 20 years or more ))

Most people (including me) use a static asset allocation. (( I theoretically target 75% stocks but my property investments mean that in practice I usually average 40% stocks ))

Assumptions

There are several assumptions underlying the lifecycle approach:

- The state pension (Social Security in the US) will survive

- This is not required for the performance simulations but is used as general planning advice to readers

- Investors have a future income (savings) stream

- If you expect no future income, you are effectively already at retirement

- You can borrow money at an interest rate that is lower than the expected return on stocks

- This is the big one, though in many situations this will be possible

Performance

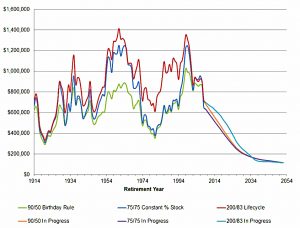

As you would imagine, the authors report performance benefits.

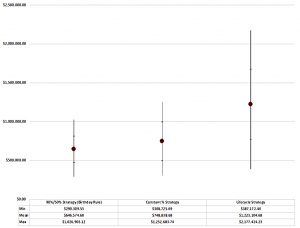

- The chart above has the constant allocation in red, the birthday rule in blue, and lifecycle in green.

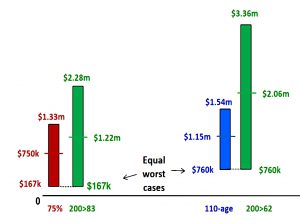

For the same worst case, you end up with higher medians and best cases.

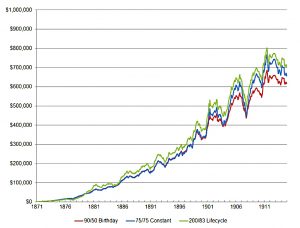

This chart compares the three options (with specific settings).

- It covers 43 years from 1871 as part of 96 historic simulations one year apart.

The 200/83 version of lifecycle investing came out on top even through market downturns.

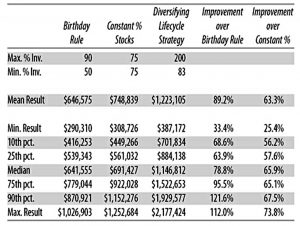

Here’s a table with more data from the simulations.

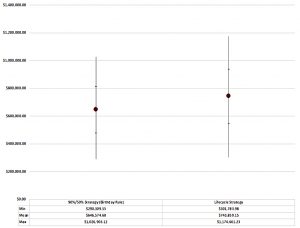

Here’s that data as a chart showing the min, max and median results for each strategy.

- Drawdowns for lifecycle were better than the constant allocation and although the volatility was higher, the Sharpe ratio was good.

The birthday rule had a Sharpe ratio of 2.12, constant had 1.84, and lifecycle had 2.06.

These are all good, by the way.

Modifying the lifecycle strategy to match the volatility of the birthday rule (26%) gives a higher median and max return.

Classify your job

Lifecycle investing assumes that your human capital is bond-like (a regular, stable income in the future).

- So if your job is very uncertain or linked to the financial markets, you might need to make modifications (have a lower proportion of stocks than lifecycle investing would recommend).

The same goes for people who own a lot of stock in the firm that they work for.

Non-job disqualifiers include a low disposable income, a lot of pre-existing debt and/or a low risk tolerance.

- The calculations (of future contributions and stock allocation from risk tolerance) are also not simple and will deter many.

Implementation

There are four ways to access leverage for investing:

- borrow against an asset (( We’ll assume that unsecured lending is not available at the scale required ))

- this could be a property, or an investment portfolio (a form of margin lending)

- regular margin/investment leverage (using CFDs or spread bets)

- leveraged ETFs (as in HFEA), and

- options

A&N recommend the use of options.

- Number 1 is likely not available to investors in their 20s and number 2 is easy for the inexperienced to mishandle.

The book also discusses likely legal barriers to accessing the strategy through a broker, investment adviser or leveraged target-date fund.

- This certainly chimes with my experience here in the UK, where leverage is seen strictly as gambling.

In the US there is a leverage 60/40 ETF (NSTX) but that’s not accessible by UK investors.

Conclusions

I’m way past the age at which it would have been useful to discover this theory, but even if I had found it back then, I doubt that I would have been brave enough to implement it.

- I don’t have any issue with the maths, but 20 years (50%) of growing contributions at say 20% of salary works out to maybe 5 to 10 years of earning.

I was pretty terrified when I borrowed three years of earnings (the max allowed at that time) to buy my first house at the age of 26.

- I don’t think that many young people would have been psychologically strong enough to borrow double that and stick it in the stock market (even if anyone would have lent them the money). (( Fun fact – the 1987 stock market crash took place a month after I bought my first house, so I don’t think I would have enjoyed sticking six years of salary into that ))

Loss aversion is a powerful force and the lack of a “lifecycle index” to use as a benchmark against which to measure foregone gains means that most people will never know what they are missing.

Decades later, the idea of allocating 5% or 10% of my net worth to a leveraged strategy like HFEA seems much less scary.

Nevertheless, lifecycle investing is an interesting topic, and I’ll be back with a review of the most common criticisms (and some rebuttals) in a future post.

- Until next time.

References

- Lifecycle Investing Executive summary – ProfessionalWealth.com.au

- Lifecycle Investing – The New Free-ish Lunch – TolusNotes

- Review of “Lifecycle Investing” – Jess Riedel – Less Wrong

- Don’t Try This At Home (Book Review) – Vermont Law Review – Frederick Vars

Thanks for the article on this. I’ve been following this book for a few years. As a UK citizen I’ve found it very hard to implement this , and would love a practical guide on how to do that in the UK context. As long as the maths works out, I have no fear of staying the course. Everyone knows investing is about staying rational and overcoming emotions. As the authors say, it’s practically no different from the mortgage mechanism.