Increasing the odds – Vanguard on Stock Returns

Today’s post is another in our occasional series on what drives Stock Returns. We look at a report from Vanguard on ways of increasing the odds that you own the stocks which drive returns.

Contents

Stock returns

We’ve looked at the drivers of stock returns twice before:

- Back in November 2018, we looked at Bessembinder’s work on how few stocks deliver positive returns.

- And a month later, we wrote about a Baillie Gifford report which gave their spin on active share.

To recap what we’ve covered so far:

- Stocks have the best returns of any asset class.

- But not all stocks beat bonds, or even have positive returns.

Bessembinder found that only 42% of US stocks had a better return than cash.

- The average stock was listed for just seven years, and the most common lifetime return was a loss of 100%.

The finding that the industry picked up on was that just 4% of listed stocks were responsible for all of the positive gains of stocks since 1926.

- Half of the growth was down to 0.4% of stocks (just 86 firms).

- Bessembinder also found that stocks are becoming less and less likely to be winners

James Anderson, manager of the wildly successful Scottish Mortgage Trust (part of the Baillie Gifford stable) attributes the success of the trust to his stock-picking abilities (rather than the stellar run of US tech stocks that he is over-exposed to.

- Since only a few stocks drive returns, these are the ones to buy, regardless of their current price.

The problem with this is that it’s another version of the larger passive / active debate:

- Active managers underperform the indices (and therefore passive funds) – as a group, because of their higher costs.

- So should you go passive, or seek out the few outperforming active managers?

And if the latter, how?

Company characteristics

Bessembinder said that large stocks did better, and those on major exchanges and with less debt also did better.

Anderson says that the winners were:

- Early entrants to markets that later became huge.

- Founder-run.

- Willing to accept / embrace uncertainty.

The first two points are hard to argue with – though there are a lot of founder-run early movers who fail, and it’s hard to identify winners in advance – but quantifying the third point is not easy.

Responses

There are three ways in which to react to Bessembinder’s finding:

- The Anderson route – work out (guess) which characteristics will lead to future success, and buy a lot of that kind of thing.

- Make sure that you are well-diversified – if it’s hard to pick the winners, you need to hold everything.

- Identify the characteristics of stocks that underperform, and avoid them.

- If 4% of the market has all the returns, then the bottom 96% is flat.

- Leave out the bottom 58% (that did worse than cash), and you’re going to do pretty well.

I advocate a combination of the second and third approaches.

Actual investing

The BG report, by partner Stuart Dunbar, advocated a return to “actual investing”, which he characterised as:

- High active share

- Low portfolio turnover

He quoted research from Petajisto and by Cremers and Pareek:

Managers with high active share and low turnover on average outperformed market cap weighted indices between 1995 and 2013 by 2.3% pa net of costs.

I don’t dispute the result or the approach, but market cap indices are a low bar that is easy to beat with passive strategies (smart beta / alternative indexing) and active ones (momentum and other factors).

Vanguard on stock returns

Now on to the Vanguard report, which is called “How to increase the odds of owning the few stocks that drive returns”.

- Vanguard don’t position the report as an attack on Bessembinder’s work.

- Instead they look at the concept of concentrated “best ideas” funds.

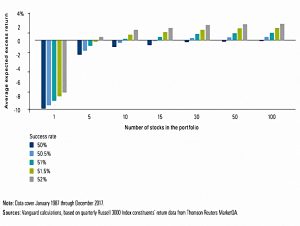

The report sets out to demonstrate that:

- Concentration lowers the odds of outperformance

- Since the portfolio is less likely to hold the few stocks that drive returns.

- Concentration does increase the odds of hitting a high outperformance target.

- But the odds of missing that target increase even more quickly with concentration than do the odds of hitting it.

- The excess return from a portfolio (above market returns) decreases as a portfolio gets bigger.

- But the success rate (percentage of outperformers) needed for outperformance also decreases as the portfolio grows.

So stock-pickers can win, but they need to get a lot of picks right.

Finding the best ideas

The idea that a portfolio’s best ideas can be extracted from a more diversified portfolio includes hindsight bias:

- It’s actually very difficult to identify a portfolio’s best ideas.

The starting point is usually the largest positions in a fund.

- Surely these are the ones in which the manager has the greatest conviction?

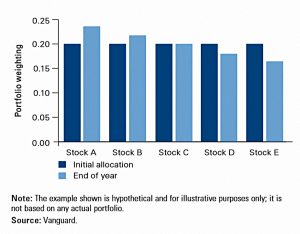

But even if a manager allocates equally to begin with, outperformers will end up as larger positions than underperformers.

- And a manager is likely to add to his winning positions, and / or cut his losers.

It might also be the case that some of the manager’s best ideas are small and / or risky companies, which means a small position in the first place.

Stock returns

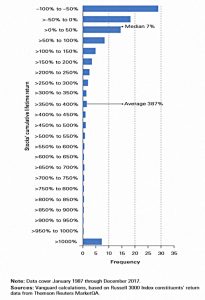

Vanguard have repeated Bessembinder’s work and found the same concentration of returns.

- They note however that the average return from a stock over it’s lifetime (387%)(is much higher than the median return (7%).

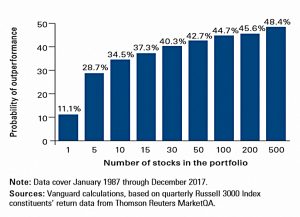

Vanguard looked at random portfolios made up of between one and 500 stocks.

- As the size of a portfolio increases, the portfolio return is likely to move towards the average from the median, sinc the chances of including an extreme winner increases.

They wanted to answer three questions:

- What is the probability that the portfolios will outperform the benchmark?

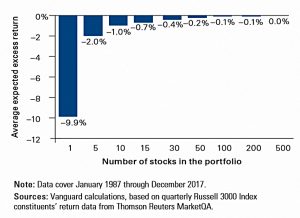

- What is the average excess return of the portfolios that outperformed and underperformed the benchmark?

- What is the expected excess return of the portfolios?

The probability of outperforming the benchmark rises quickly (from a low level), and continues to increases right up to 500 stocks, though it never hits 50%.

- From this chart, it’s hard to argue in favour of (random) portfolios smaller than 50 stocks.

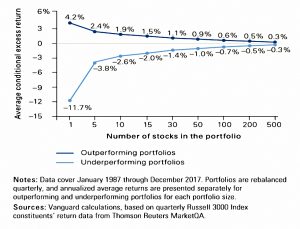

As portfolio size increases, the outperforming portfolios outperform by less, and the underperforming portfolios underperform by less.

- Performance converges to the market average.

The underperformance decreases.

- For some reason, Vanguard prefers to call this a “rising excess return”, even though it’s negative.

This is because picking one stock gives you a good chance of hitting the median, whereas a large portfolio is likely to have av average (higher) performance.

Tracking error also decreases with size, as you would expect.

Other targets

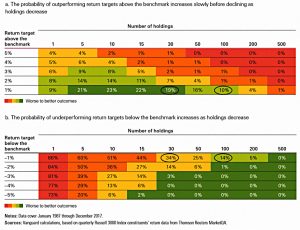

Vanguard also looked at the probability of hitting or exceeded return targets above the benchmark.

- And at the probability of hitting or underperforming return targets below the benchmark.

The relationship is nonlinear.

- To hit high targets, some concentration helps (though the probabilities involved are low).

- Concentration also makes you more likely to underperform low targets.

This tallies with the convergence of returns we saw above.

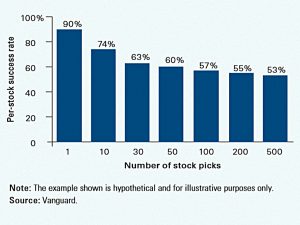

The hit rate (success rate of individual stocks) required for a 10-stock portfolio to outperform is 74%.

- With 50 stocks, this drops to 60%.

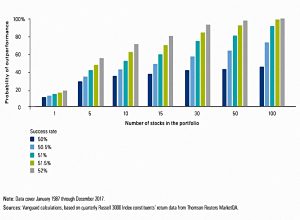

This chart shows how slightly varying the success rate impacts the probability that portfolios of various sizes will outperform.

And this one shows the magnitude of the out- (or under-) performance.

- With 30 or more stocks, you’ll outperform once your hit rate gets above 50%.

Fund history

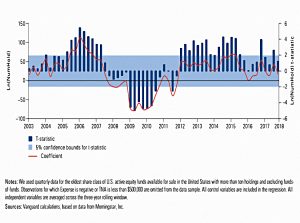

Vanguard also looked at whether concentrated funds have outperformed historically.

In general, larger funds outperformed over the last 15 years, though there have been years when this is not the case.

Morningstar

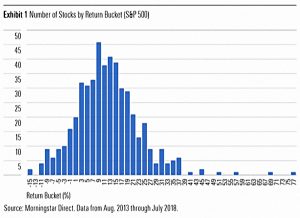

Morningstar also carried an article in response to the Bessembinder findings, entitled Why Diversification Beats Conviction.

As portfolio concentration increases, so do the odds of underperforming the market.

They make the following observations:

The right-hand tail is longer than the left-hand tail, which pulled the average return of the stocks in the index slightly above the median and created a modest positive skew.

Whenever there is a limited lower bound and no upper bound, it is common to find that a few observations have a disproportionate impact on the average.

Compounding tends to increase this positive skewness over time.

They come to similar conclusions to Vanguard:

Investing in a concentrated portfolio is a bad idea because the opportunity cost of missing the market’s big winners exceeds the benefits of avoiding the (many) losers.

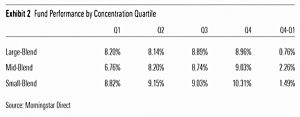

And they also show that the last decade of mutual fund performance fits this pattern:

I grouped active mutual fund managers into quartiles based on the percentage of assets invested in their top 10 holdings at the end of June each year from 2008 through 2017.

The more concentrated the portfolio, the greater the risk of missing out on the biggest winners.

- This is particularly true for small cap and mid cap funds.

Concentrated active managers who do catch some of the big winners can crush the market, but the odds are against them.

Conclusions

Vanguard draw five conclusions:

- Historical market returns are determined by a small minority of stocks.

- A more diversified portfolio is more likely to hold these outperforming stocks while displaying a lower dispersion of portfolio returns.

- Portfolios with fewer holdings underperformed those with more holdings.

- Decreasing the number of holdings increased the chance of outperformance but came with an even higher probability of underperformance by the same target.

- Investors who believe their stock-selection ability is better than chance would be best served applying that skill by selecting more stocks, not fewer.

- Increased diversification yielded higher returns from mutual funds.

I agree with each of those.

Until next time.