The right time to buy an annuity

Today’s post looks at a paper from LCP on whether there is a right time to buy an annuity.

Contents

The right time to buy an annuity

The report was written by Steve Webb, who used to be the Pensions Minister and Philip Boyle.

- They are both partners at LCP.

The question which this paper seeks to address is whether the attractiveness of an annuity changes as you go through retirement.

Annuities

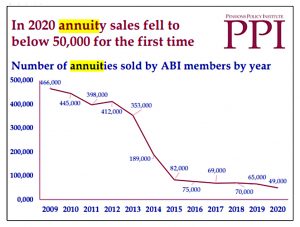

Until George Osborne’s Pension Freedoms of 2015, most people with DC pensions (other than those with very small or very large pots) were forced to use 75% of that pot (after taking the 25% tax-free lump sum) to buy an annuity.

- For a long time, this wasn’t a big problem, but as interest rates fell and life expectancies rose, the returns from annuities also fell, until they offered very poor value.

Once the rules were changed, and flexible drawdown and UFPLS were made available to everyone, few people continued to buy annuities.

Mortality risk

The thesis of the paper is that attitudes to annuities might change as people age since mortality risk (the risk of living longer than you expect – or as the paper defines it, the risk of living longer than the average person) increases as you get older.

This means that managing a drawdown pot to make sure that you don’t run out of money (on the one hand) or end up living excessively frugally to avoid the risk of running out (on the other hand) becomes steadily more difficult as you get older.

That’s quite the leap. The difficulty of managing your pension pot in drawdown will depend to a great extent on two factors:

- The size of your pot (or equivalently, the withdrawal rate that you need to live on)

- Your investment allocation and performance (which are related over the long term)

The paper hasn’t made any statements on either of these so far, so it’s quite a blanket assumption that things must get harder.

- Many people will end up with final pots that are several times the size of the pot they started with, despite drawing an income each year.

Mortality by age

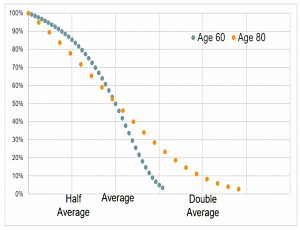

By definition, 50% of people live to the average (median) age, but the distribution of outcomes away from the average is quite different for the 60 year-old compared to the 80 year-old.

The 60 year-old man has almost no chance of living double the average, whereas the 80 year-old man has to consider this a realistic possibility.

I take the general point that the chances of living longer increase with age but, your remaining expected lifespan does not increase with age – it shrinks.

- What LCP mean is that at age 60, the expected lifespan is 26, and living to 112 (52 years, or double the average remaining lifespan) is very unlikely.

At 80, the average lifespan is 9 years, and living to 98 (double the average) is a real possibility (a 6% chance, actually).

- But those 18 years are still less than the average of 26 years at age 60.

If the pension pot has been managed properly in the interim, the risk of exhaustion is lower than at age 60.

- So by the RCP logic, an annuity would be less attractive at 80 than at 60 (though the annuity rates available would be much higher, so that needs to be factored in).

The LCP model

LCP has built a utility (happiness) model based on three assumptions:

- ‘Upside’ – we assume that people will be happier if their annual income in retirement goes up rather than goes down;

- ‘Avoiding downside’ – we assume that people will be very unhappy if their annual income falls in retirement;

- ‘Bequests’ – we assume that people may attach some value to having an unspent balance when they die which can be left as an inheritance to their heirs

These are all reasonable, but the weighting of each will be different for each individual and is hard to calculate.

- On these three measures, annuities score well on downside protection, but badly on the other two scores.

One general finding is that downside protection is valued more highly than upside.

- Another is that money today (income) is valued more than money in the future (bequests).

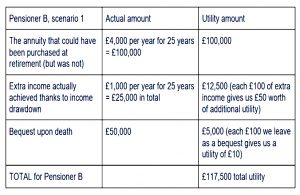

The LCP model assumes a baseline annuity income where £1 of income provides £1 of utility, but the extra income from flexible drawdown is worth only 50p of utility per £1 of income.

- Where drawdown provides a lower income, each £1 of lost income is assumed to translate into £2 of pain (negative utility).

Note that using my preferred strategy of a flat failsafe withdrawal rate (of 3.33%), there is no loss from drawdown – you can withdraw that level of income indefinitely.

LCP also assume that bequests are worth only 10% of money spent during life – each £1 of a bequest provides just 10p of utility.

Let’s put some real-world numbers on this:

- A £100K pension pot currently provides an indexed annuity income at age 60 of £2,070.

- In drawdown, a failsafe withdrawal rate of 3.33% would provide an income of £3,333.

- That’s 161% of the annuity income, but LCP will value this at only 130%, by halving the upside.

There’s some truth to this law of diminishing returns, but another way to look at the extra drawdown income is that it allows you to retire with a smaller pot.

- If you need £25K to live on, then you need a £1.2M pension pot to fund the required annuity.

With drawdown, your pot “only” needs to be £750K.

Examples

The LCP example assumes a 60-year-old who takes out a 4% flat annuity and lives neatly for 25 years so that he gets his £100K back in the end.

- That annuity is certainly available, but the calculation ignores inflation and assumes that the £4K of income (or whatever multiple of that is actually purchased) will still be enough to live on after 25 years.

The comparison is with £5K of drawdown income and a terminal value (bequest) of £50K.

- This leads to £115.5K of utility (100 + 12.5 + 5).

I would argue that the drawdown investor would actually take only £3.3K pa and would end up (on average) with a much larger pot to bequest.

- So we are not comparing apples with apples and the LCP utility calculations don’t make sense.

Their analysis seems to be aimed at retirees with pots that are too small, and who therefore need to withdraw more each year to live on than is prudent for optimal pension management.

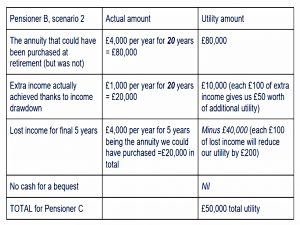

LCP’s second scenario assumes poor investment returns and the pot being depleted after 20 years (at £5K pa – this is actually zero returns over 20 years, which is pretty pessimistic.

- This adds up to a total utility of £50K (80 + 10 – 40).

Scenarios

The rest of the paper looks at variables that could potentially affect the annuity/drawdown decision.

- Note that this decision exists only in the LCP model – taking a failsafe withdrawal from a big enough pot can’t be beaten by using annuities.

The scenarios involve the following assumptions:

- a flat annuity at age 60 of 3.87% pa

- higher rates are available but LCP say this would be the average rate across the entire population

- I understand that most people buy flat annuities, but I still think this is not the best comparator for drawdown

- drawdowns at 130% of the annuity, or 5.03% pa

- This is an unsustainable withdrawal rate – someone who needs to draw this much hasn’t saved enough in their pot

- A true comparison would be an indexed annuity of 2.07% against a failsafe drawdown of 3.33%

- a 55/45 stock-bond split

- 1.2% pa return on bonds

- inflation of 3.3%

- an expense ratio on the drawdown product of 0.9% (a tad high for me – my annual costs are 0.34% at the moment)

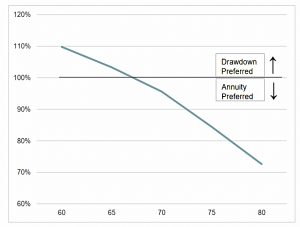

Here’s the baseline scenario – the crossover to annuities happens around age 67.

More risk

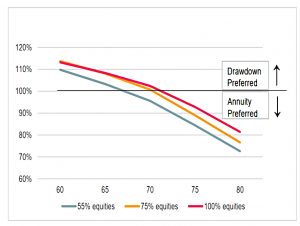

Upping the equity allocation increases the cross-over age to your early 70s.

More aggressive drawdown

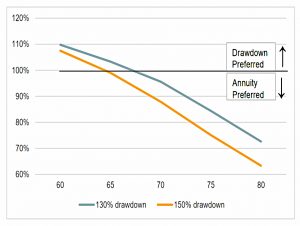

Not surprisingly, using a more aggressive drawdown rate (5.8% pa!) pulls the crossover age forwards.

Index-linked annuity

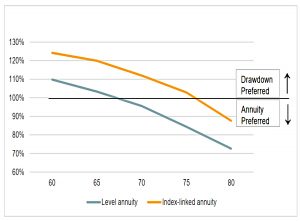

Using an index-linked annuity pushes the cross-over age out to 77.

Greater risk aversion

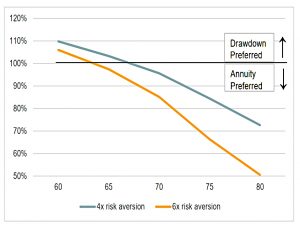

Increasing risk aversion from 4x (up is 50p, down is £2) to 6x pulls the cross-over age forwards.

Bequests

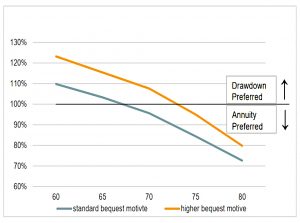

Increasing the utility of a £100 bequest from £10 to £25 makes the drawdown option more attractive.

- This is not surprising, since buying an annuity leaves no money behind for a bequest.

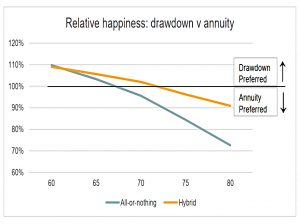

Hybrid approach

The baseline assumes a 45% allocation to bonds.

- In a hybrid approach, this 45% is used to buy an annuity, and the remaining 55% stays in stocks.

This pushes the crossover age out by a few years.

Conclusions

Annuities remind me of communism – a bad idea that refuses to die. (( Hat tip to Kristian Niemitz, who wrote a book with this title ))

- They don’t work in a world of long lives and low interest rates, but the finance industry doesn’t seem to have caught on.

The LCP model in today’s paper doesn’t connect with me at all.

- I don’t have an issue in principle with a utility model (although setting the right weights would not be easy)

- But comparing flat annuities to withdrawal rates above 5% pa just doesn’t match up to the real world of DIY investors working towards financial independence.

Index-linked annuities pay 2.1% pa at age 60, and you would struggle to not beat that over 30 years with your investment pot.

- Flat annuities pay 4% pa but require heroic assumptions about the future path of inflation over 25 or 35 years.

The best plan is to retire when your pot reaches 33 times your target income, and withdraw 3.3% pa.

- That way your pot should last indefinitely, and under extreme (never-seen-before) circumstances, you would simply run down the size of your eventual bequest.

Until next time.