Weekly Roundup, 11th April 2017

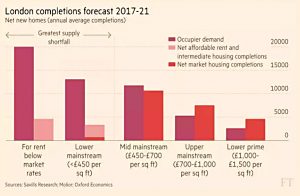

We start today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with The Chart That Tells A Story. This week it was about London property completions.

Contents

London property completions

James Pickford looked at five-year London housing supply projections from Savills.

- 46,000 homes will be completed in London this year, up from 41,000 in 2016.

- This is the highest number since the 1930s.

- It’s more than the Mayor’s minimum target of 42,000, but fewer than the 64,00 new jobs that will be created in the city.

There’s also a mismatch between supply and demand:

- The greatest demand, not surprisingly, is for the cheapest houses – less than £450 per square ft.

- There’s even more demand for rentals at below market rates.

- The highest supply is in the mid-market (£450 to £700 per sq ft).

At the bottom end of the market, there’s more demand than supply, while at the top end there’s more supply than demand.

Prices at the top end have dropped since stamp duty was increased in 2014.

- There was a further impact when the additional rate of 3% was added to second homes last year.

At the bottom end, the Government’s Help to Buy scheme affects less than 10% of sales, since the £600K cap is too low for London.

This is likely the high water mark for completions.

- Starts on homes in Zone 1 and 2 dropped by 75% in 4Q2016 to the lowest level since 2011.

- And Savills is predicting a drop to 35,000 completions by 2021.

Probate fees

Javier Espinosa reported that the government plans to press ahead with the probate fee increases we discussed a few weeks ago, even though a parliamentary committee has said that the rises are unlawful.

Four big questions

It’s Passover this week, and John Authers adapted the tradition of asking four questions from the religious festival to the markets:

- Why is volatility near historic lows?

- Low yields make bonds unattractive, so money must go elsewhere.

- Low real(post-inflation) interest rates also keep the cost of money low.

- More worryingly, some traders are “selling volatility”, which in itself reduces volatility – this is an accident waiting to happen.

- Why is the US stock market outperforming?

- US economic data looks good, and rates remain fairly low.

- Why are UK assets doing so well?

- Partly this is the flattering effect of sterling’s devaluation.

- Second, there was no panic selling after Brexit.

- Third, Brexit has increased consumption rather than reduced it.

- How can bond yields still be so low?

- Partly this in down to central bank policy, though all are signalling tighter conditions from here.

- John suggests demographics are to blame.

- Ageing populations mean that pension funds buy more bonds, which pushes up prices and lowers yields (which in turn means that more bonds are needed).

- Or possibly bond investors are as pessimistic as equity investors are optimistic – they don’t believe the growth and reflation story, so bonds are the safest bet.

UK economy

Chris Giles looked at conflicting indicators on the health of the UK economy in 1Q2017.

Industrial output fell in January and February, and the January figures for services were disappointing.

- But the PMI (purchasing managers’ ) survey numbers are more encouraging.

Consumer spending accounts for 60% of the UK economy, and retail sales were down 1.4% in the three months to February.

- But retail is only one-third of consumer sales and car purchases hit record levels in March.

- Credit card data showed spending is being shifted from things to experiences (eg. restaurants).

House price growth slowed to 3.8% (Halifax) or 3.5% (Nationwide) in March, but remains positive.

The CBI reports that exporter confidence is at a 20-year high, and orders are at a 3-year high.

- But imports are up as well as exports, and the trade gap of £8.7bn is only slightly below the £9.1bn average for the past year.

- Weaker sterling is expected to boost exports in the future.

So far, the economy remains on target for 2% growth in 2017, but rising inflation and low wage growth may impact this in the second half of the year.

Immigration

Tim Harford wrote about immigration, which economists tend to view as a good thing, but which politicians (and the public) are wary of.

- Tim uses the golden rule of “do unto others” to persuade us to feel grateful to immigrants, but he failed to convince me.

He starts by trying to equate immigrants with ex-pats.

- But expats generally move to poorer countries and immigrants generally come to richer ones.

And he once again tries to argue that an assessment of whether there is a net cost or a net benefit to immigration must include the benefits to the immigrants themselves.

- By that logic, me being mugged in the street is a neutral event.

- I’m down a smartphone and the robber is ahead by one.

Immigration is a good thing, up to a point.

- It brings in needed skills and improves the ratio of young, working people to old retired ones.

- But it also keeps wages low and displaces unskilled locals from the workforce. (( Yes, I am aware of the “lump of labour fallacy” – I’ll be quoting it in a later section of this article ))

- And in the extreme, it irrevocably changes a country’s culture.

So it’s quite possible that Britain has had enough of it, as evidenced by the Brexit vote.

Lifetime pension allowance

In the Telegraph, Ros Altmann wrote about the perverse incentives of the lifetime allowance (LTA) for pensions.

The lifetime allowance has a number of flaws:

- Down to £1M from £1.8M in 2012, the allowance is not overly generous

- In drawdown, you might get £35K pa from that pot, which is plenty

- But you would get a lot less if you converted it to an annuity – £25K at age 55 with indexing

And if you stick with drawdown, you could only draw for 28 years before hitting the limit

- If you retire at 55, this takes you to 83, which many people will outlive

The lTA also favours DB pensions over DC ones, by converting them at only 20 times their annual payout, rather than an accurate 28 times.

- This means that a DB pension can reach £50K pa before breaching the limit.

- And it can be paid out for as many years as required.

But the real problem is that unlike the annual limits on ISA and pension contributions, it is calculated on the money you take out rather than what you put in.

- Which means that it’s almost impossible to work out when you’ve contributed too much.

The future value of your pot depends not only on how much you put in, but also on your investment performance.

- With payments over £1M taxed at 55%, this is an expensive mistake to make.

Ros’ specific complaint was that many GPs are quitting in their 50s, because their pension pots are full.

- The same applies to other public sector workers such as police chiefs, firemen and head teachers.

They are all retiring early to keep their pensions below £50K pa.

- They get less per year, but for more years, and may eventually come out ahead even without taking into account the tax they have dodged.

For those with DC pensions, the problem is knowing when to stop.

- Once you have £700K or £800K in your SIPP, you can reasonably assume you will breach the limit in the end, and further contributions make no sense.

Tax burden

In Money Marketing, Paul Lewis wrote about how he doesn’t believe in the tax burden.

- He receives sufficient benefits from the state that he doesn’t see it as a burden.

- I wish I could say the same.

The B-word came up during the post-Budget discussions on whether the self-employed should have the same NIC burden as the employed, and also in reports that the richest 1% pay 27% of tax.

Paul rightly points out that this is 27% of income tax, not all taxes, and that “richest” is defined in terms of income not wealth.

VAT and NIC are the other big taxes, and when these are taken into account, the bottom 10% (of non-retired households) pay 38% in taxes, which the top 10% pay only 32%.

So far, so good – but why stop there?

- If we’re going to include VAT and NIC, we should also add in the value of benefits from the state.

When we do that, the picture becomes very different.

- Depending on the calculations and assumptions you use, somewhere between 30% and 50% of people are net contributors to the system, and between 50% and 70% are net beneficiaries.

So the burden falls not on the poor, but the rich.

- It falls on the givers, rather than the takers.

US stocks weighting

In the Economist, Buttonwood was worried about the heavy weighting to US stocks in the global index.

- The US now makes up a record 54% of the index, as it did in 2002.

- In the developed markets index the US now contributes 60.5%.

- So a global tracker is largely a bet on the US.

Buttonwood sees parallels with the way that Japan dominated the index in the 1980s.

- At its peak, Japan made up 44% of the index, more than double its share of global GDP.

- And we all know how well that turned out.

- Japan is now less than 10% of the global index, and close to its GDP share.

The US is currently at double its GDP share, which has fallen since 2000.

- But half of the S&P-500’s profits are made abroad.

- Though highly valued, US ratings are much lower than they were in Japan in the 1980s.

- And the tech giants of the US may have “natural monopolies”.

The US market may not crash, but investors in low-cost “safe” global index funds should realise what they are getting into.

Funding for business

The newspaper also reported on government plans to use pension funds as a source of patient capital for tech firms and others.

- 650K firms were formed in 2016, a record, and London is full of startup incubators and accelerators

- But long-term capital remains hard to find.

So the government has set up a review that will report in time for the Autumn Budget.

- The particular concern is firms between £5M and £100M.

Britain invested £2 bn of venture capital cash into tech firms last year, which is better than Europe but much lower than the US ($42 bn).

- The Business Growth Fund backed by five big banks contributed £400M of that.

But UK venture capital is mostly interested in a 10-year investment rather than the 30 years needed by life-sciences companies.

- So 60% of UK funding rounds above £10M look to the US.

George Osborne had been pushing pension funds to invest in fewer bonds and more risky startups, and it’s likely that the the new review will draw the same conclusion.

- This might involve bundling the UKs 300 public sector funds together, as has been done in Canada.

- And the new larger pension funds might be allowed to invest in VCTs, which (now we are leaving the EU) could be reformed to accommodate the larger sums involved.

Four day week

We close with a belated April Fools’ joke from the Green Party, which wants to create a mandatory four-day working week.

- They think this would reduce inequality between men and women (presumably because they think men would be keen to use their extra day to catch up with housework).

That’s not the funny bit – a lot of people would like to work one day less, and god knows there’s enough time wasted in offices to make it theoretically possible to get the work done in less time.

- The Green’s don’t want to redistribute 40 hours of work into four 10-hour days, they want to cut the week to 32 hours.

And they want to give everybody a 20% pay rise, so that they get the same money for 32 hours as they used to for 40.

- This would cost £120 bn a year – about the same as the NHS. (( This reminds me of their plan to fund a basic income ))

The pay rise would neatly avoid the problem that people earning less would spend less, and therefore less work would be needed.

- Without the extra cash, the Green’s plan would be guilty of the “lump of labour” fallacy. (( The Economist appears to have missed the fact that the extra payments mean this isn’t the case ))

So the plan requires a 25% increase in productivity to be self-funding.

- This is surely possible, but if I offered to pay you five days money for four days work, would you start to work harder?

Until next time.