Weekly Roundup, 18th April 2017

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with The Chart That Tells A Story. This week it was about IP companies.

Contents

IP companies

Aime Williams compared the performance of Allied Minds with that of IP Group and Touchstone Innovations (formerly Imperial Innovations), its main rivals.

- Touchstone is the oldest of the three, formed in 1986.

- IP is the largest at £800M market cap and forms part of the FTSE-250.

Going back to June 2014, Allied soared at first, before falling back to earth.

- This was despite Allied being lost making ($52M on $13M of revenues in 1H2016).

- The crash was precipitated by a new CEO writing down / writing off seven of its investments.

- All three companies are now underwater compared to 2014.

Allied Minds is a big holding of Neil Woodford’s and is also held by Mark Barnett, who took over Woodford’s funds at Invesco Perpetual when Woodford left to set up his own asset management company.

- Between them they own two-thirds of the company.

The lesson here is beware “the Woodford effect”.

Free stockbroking

Aime’s second article of the week looked at the launch later this year of Freetrade, an app aimed at millennials that will offer free trading for portfolios under £10K.

- This follows the launch of a similar app – RobinHood- in the US a couple of years ago.

“Everyone in the UK right now is designing products for a 50-year-old man with a large portfolio” said Adam Dodds, Freetrade founder.

- This is news to me – if anyone is interested, I’d love to help design some products aimed at me.

Much as I would love a free broker, I’m not convinced.

- An ISA account comes with a £36 annual fee, whereas as many are free at the moment.

- And accounts above £10K will be charged 1% pa, which means a minimum of £100 pa.

So I can’t see how there will be any paying accounts to subsidise the kids with less than £10K.

Robo-advice guidelines

Aime’s third article was about the FCA updating their guidelines on advice to take account of robo-advisers.

- I had hoped that this would involve a clearer distinction between (regulated) advice and (non-regulated) guidance.

But in the end it just amounted to a new category of advice called “streamlined advice”.

- It’s a less onerous standard of advice that at current, but it’s still regulated, so not of much interest to me.

Since the RDR, two thirds of financial products are now bought without advice.

- Advisors charging £150 per hour are too expensive for investors with less than £100K in assets.

- They are too expensive for me, as well.

Another category of regulated advice than can be given via online questionnaires is intended to solve this, but it seems to me that only those operating platforms and / or in-house funds will be able to make this model work.

Rich pay more tax

Another writer with more than one article of interest this week was Vanessa Houlder.

- Her first was about how much tax the rich pay, a topic we discussed last week.

The average rate of income tax for someone on 167% of the average wage (22% on £61K) is now double that of someone on 67% of the average (11% on £24.5K).

- This makes the UK tax system more progressive than the OECD average.

- In 2000, only seven OECD countries had a less progressive system.

The increase in the personal allowance from £4,385 to £11,500 is largely responsible.

- This has pushed the percentage for the 67% worker down from 15% and that for the 167% worker down from 23%.

It’s more complicated when you look at households, since the poorest households have no taxpayers and the richer ones often contain two people who have benefited from the rise in the personal allowance.

- And since poorer people spend more of their income, indirect taxes like VAT need to be taken into account.

And as we said last week, the effect of benefits needs to be included.

- The upper quintile of UK households earned £84K gross in 2014-15, compared to just £6K for the lowest quintile.

- After taxes and benefits, these numbers change to £62.5K and £16.5K.

Inheritance row

Vanessa’s second article was about an inheritance tax row.

- A couple in their 80s who placed £17M of property (including jewellry, antiques and art) in a trust for their children are suing for its return.

Manny Davidson, the father, has previously warned parents to “keep your money and spend it on what you want”.

- This was back in 2015, when the children put his (now their) Jacobean mansion up for sale against his wishes.

- The children also sued to remove their parents’ right to appoint the trustees to the trust which controls all the family assets.

I have to say that I agree with Manny – don’t give anything away that you might want to see again.

And until the problems surrounding care fees are resolved – hopefully via the introduction of the promised £72K per person cap, and the subsequent development of an insurance market around it – it will be very difficult for retirees to work out how much they can afford to give away.

Glass-Steagall

John Authers looked back to a previous Easter week that signalled the end of the 1933 Glass-Steagall act that separated commercial and investment banks and insurance companies:

- In 1998 Citibank and Travellers merged, as did BankAmerica and NationsBank.

- Ten years later both combined groups came under pressure during the 2008 crisis.

Both US parties called for the return of Glass-Steagall during last year’s election.

- Even Trump seems interested.

I’m in favour of restoring the separation, but untangling the mess we have at present won’t be straightforward.

- And as John points out, restoring the act wouldn’t rid us of banks that are “too big to fail”.

Brewdog

The Times (( Behind a paywall, so no link )) reported that Brewdog has sold a 22.3% stake to US private equity firm TSG Consumer Partners.

- The £213M paid values the firm at just under £1bn, which almost makes it a rare (and publicity-friendly) UK “unicorn”.

- The firm made £7M in pre-tax-profits in 2016, on £71M of turnover.

A lot of the money will go to the two founders, who stand to make more than £100M between them.

- These two guys were given MBEs in 2016.

“Crowdfunding can no longer be viewed as alternative finance; this is the democratisation of finance,” said one of them in an update to shareholders.

Really?

Ordinary crowdfunding “equity for punks” investors won’t do so well out of the deal:

- Though the typical £1K investment in 2011 now has a paper valuation of £26K, crowdfunding investors can sell only 40 shares (worth £530) in the deal.

- Pre-emption rights have also been removed, which means that crowdfunders can’t buy more shares to maintain their percentage holding.

To me, this deal stinks – at the very least every investor should be able to sell 22.3% of their holdings.

- This would raise £5.8K for a £1K investor, which is a handsome profit whatever happens to the other 80%.

The one defence for the company is that these turkeys voted for Xmas.

- 95% of shareholders recently approved a plan that involves share dilution, more stock for managers, and preferred shares (yielding 18% pa if the company is bought or floats) for TSG.

The stock market canary

Also in the Times, Ian Cowie looked at when (or whether) to get out of the stock market.

- Like me, he sees none of the euphoria that has characterised recent blow-offs.

He’s been asking asset managers for their warning signs:

- CAPE is at 29 (for the S&P 500), compared to a long-term average of 15

- but CAPE was at 28 when Alan Greenspan warned of “irrational exuberance” in 1996, and the market went up for three more years after that

- the same thing happened in 2005

- Interest rates remain low, increasing the value of future (inflation-linked) returns from equities

- so a lot of rate rises from the Fed (perhaps to combat inflation) would be bad news

- Increased defaults in high yield (“junk”) bonds would also be a bad sign

- Falls in the PMI index or in consumer confidence (especially in the Eurozone) should also be watched for

- And the legendary “stock tips from cabbies” (( This was originally shoeshine boys and elevator operators, but both occupations are now much rarer ))

Ian remains fully invested and watching for greed to replace fear in a euphoric market.

Gold

Over in the Economist, Buttonwood looked at why gold has not responded to the risks of reflation and geopolitics.

The fundamentals are not good:

- Jewellery demand fell by 38% in India (because of a new duty) and by 18% in China.

- And net central bank buying dropped to a seven-year low.

Because gold has no income, there is no absolute valuation measure.

- It’s best seen as an alternative currency to the dollar.

- And holding it has a higher cost when interest rates (on cash) are high.

Thus the Trump trade (higher interest rates and a stronger dollar) was not good for gold.

Although the Trump trade has faded recently, so has the threat of trade wars or actual wars.

- Buying gold at the moment is mostly insurance against something going badly wrong.

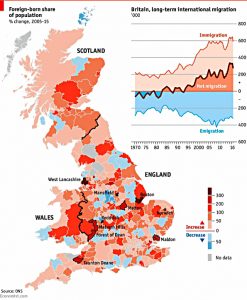

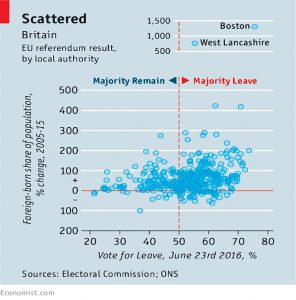

Immigration

The newspaper also looked at the apparent paradox that while immigration should be good for the UK economy, the places in the country with the biggest recent influxes are not doing well.

The usefulness of skilled and hard-working immigrants is not in doubt, but they are not popular:

- 50% want immigration reduced by “a lot” and only 5% want more of it.

To try to understand this, the Economist looked at the 10 local authorities (mostly small towns with little previous immigration) that had the largest percentage change from 2005 to 2015.

- They called these towns “Migrantland”.

- All ten saw at least a doubling in the “foreign-born share”.

The first finding was that Migrantland was pro-Brexit by 60 to 40.

- While there was no link between the Brexit vote at the absolute level of immigrants across the UK, a recent increase in the level of immigrants did lead to a bigger Brexit vote.

A lot of the jobs on offer are low-pay and low-skill (fruit-picking for example).

- Which means that the immigrants are often poorly-educated and don’t speak good English.

And every 1% increase in the proportion of immigrants reduces wages for low-paid locals by 0.5%.

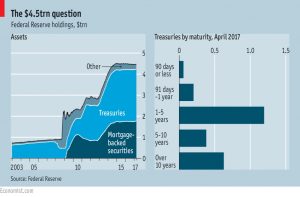

Federal reserve balance sheet

The Economist also argued that the Fed should keep a large balance-sheet.

- The balance-sheet grew from $900 bn before the 2008 crisis to $4.5 trn in 2015.

- This was largely because of QE, as the Fed bought mortgage-back securities and government debt.

QE is supposed to be unwound later this year, with the Fed “retiring” the money it created to buy these assets.

The Economist suggests that the balance sheet needs to be at least $2.5 trn to supply banks with sufficient reserves.

- This should increase financial stability by displacing risky bank-issued short-term debt with government supported debt.

- The cost is that long-term bond yields remain low.

One way to fix this would be to retire long-term debt and replace it with short-term debt.

- I confess to not understanding how this mechanism would work.

- For long-term yields to rise, prices must fall, which implies less demand or greater supply.

The newspaper also suggests letting firms and individuals open (interest-bearing) accounts at the Fed, rather than just banks.

Stagnation and populism

I’m grateful to MoneyWeek for pointing me at a paper called “The Deep Causes of Secular Stagnation and Populism“, written by James Montier and Philip Pilkington of GMO.

It’s a long paper that blames neo-liberalism (globalisation, flexible labour markets, shareholder returns etc) for our current ills.

Removing neo-liberalism is not part of my personal agenda, but the paper includes a couple of good ideas for any government:

- take responsibility for full employment by offering a minimum wage to anyone who offers their labour

- when private firms don’t need this labour, the government would organise “good works” (helping the elderly and disabled, public gardens and environmental projects) to soak it up

- promote import substitution by identifying products which could be made locally and subsidising them as part of a re-industrialisation policy

There are some bad ideas in there too (more unions, penalising shareholder value maximisation) but let’s stay above the line for now.

Pensions dashboard

And finally, Henry Tapper over at the Pension Playpen gave me my first look at what the planned Pensions Dashboard might look like:

No surprises here, but it’s always good to have a heads up.

Until next time.