Weekly Roundup, 14th September 2020

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in The Times, with a couple of articles about tax.

Tax

There are probably still more than 10 weeks to go until the third and final budget of 2020.

- But following a leak of Chancellor Rishi Sunak’s notes for a meeting with Tory MPs, there is already quite a lot of speculation in the press about which taxes might go up to pay for the Covid-19 bailout.

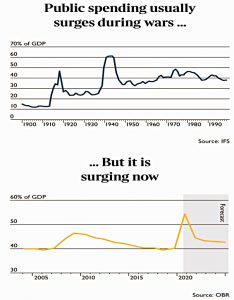

David Smith pointed out in The Times that the OBR is projecting public spending to hit 54% of GDP this year.

- Spending is obviously up, and GDP will be down, perhaps by 12%.

That compares with 46% in 1976 when Britain had to borrow money from the IMF.

- It was also 46% in 2009-10, prompting the coalition government to introduce “austerity”.

Spending has only been higher than this year during wartime.

The real problem is that a budget deficit of 5% is predicted as far out as 2024-25, when government spending should be back down to around 42% of GDP.

- Which is why higher taxes are on the agenda for a Tory government.

Of course, you need to choose carefully, because higher taxes have a habit of not translating into higher government revenue.

- This is partly because recessions lower revenue in any case, and partly because it has been hard historically to collect more than around 38% of GDP in tax.

To get the 2024-254 deficit down to 2%, we’d need to raise 40% in tax.

- The last time that happened was in 1983, with privatisation receipts, North Sea oil revenues and income tax rates of 30% to 60%.

In the same paper, Mark Littlewood also looked at potential tax rises.

- He started by pointing out that the national debt has passed both £2 bn and 100% of GDP and that this year’s deficit is likely to be the largest ever by a factor of three or four.

Naturally, the Treasury would like to raise taxes in order to shore up their credibility, but can this be done without choking off any recovery?

- A higher future growth rate is probably the best defence against future catastrophic levels in the debt-to-GDP ratio.

Mark says that the economic literature shows 20% (of GDP) to be the optimum level of state spending for maximum growth.

- If you add in maximising welfare, this rises to 30%.

As we noted above, the maximum sustainable spend (ie. tax-raising capacity) is around 38%.

- Sadly, Britain has exceeded 38% for many years.

Flat Tax

Over in Money Week, Simon Wilson argued in favour of a flat tax – say 20%.

- This might in theory cover income, NICs, corporation tax, VAT and IHT, but most plans just look at income tax.

A large personal tax-free allowance is also needed to make sure that tax remains progressive at lower incomes.

By simplifying the tax code – and making the single rate sufficiently low – you save people and businesses time and money, drive up compliance rates by reducing the incentive for tax evasion or avoidance and stimulate the economy by increasing the incentives for extra effort and risk-taking.

The idea is that a lower headline rate will nevertheless raise more revenue.

Flat-taxes haven’t really be tried outside of Russia and Eastern Europe, in relatively poor countries with weak governance.

- It would be a tough sell here since most of the big losers would be in the middle of the income distribution.

In that sense, it reminds me of the left’s “good idea in theory” – a universal basic income.

Educated money

Joachim Klement looked at educated money, which is his term for what other people call the smart money.

- In particular, he looked at a study which examined which investors take the right and wrong side of trades.

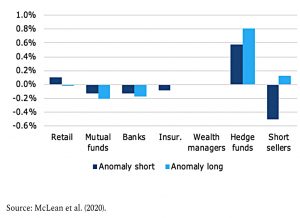

McLean et al looked at 130 anomalies/factors were treated by various investor classes.

Retail investors on average increased their positions in stocks that should be shorted. So they ended up on the wrong side of the trade. They [also] reduced their positions in stocks that should be bought. Again, they ended up on the wrong side of the trade.

Mutual funds, banks, and insurance companies tended to sell both kinds of stocks, whilst hedge funds tended to buy both types.

The only investor group that did the right thing on both sides of the trade and thus the educated money in the market are short-sellers.

Investment trusts

In the FT, John Kay looked back on a lifetime in investment trusts.

- He’s been an investor in and board member of ITs for almost 40 years and recently retired as the senior independent director at the Scottish Mortgage Trust (SMT).

John is a big fan of the sector and walks his readers through its history.

He also compares ITs to their historic rivals mutual funds (in the US – unit trusts and later OEICs here in the UK).

Unit trusts historically had two marketing advantages over investment trusts — they could be advertised to potential investors, and they could pay commission to intermediaries.

These advantages – which accrued in any case to the intermediaries and managers, rather than to investors – have now been removed, but open-ended funds remain more popular than ITs.

John also touches on venture capital, active share and the Woodford scandal.

- The article is worth a read, but it does exhibit the FT’s recent penchant for advertorial – in this case, providing a boost for SMT and its managers.

Blunt ratio

In the last two editions of the Verdad newsletter, Brian Chingono and Nick Schmitz took a look at the Sharpe ratio, or as they call it, the Blunt Ratio.

They start by asking why traditional measures of financial risk (eg. standard deviation) treat positive surprises in the same way as negative surprises.

- Taleb has a new book out arguing against the use of standard deviation (SDs), beta and Sharpe ratios (SRs) with variables that have fat tails (such as stock returns).

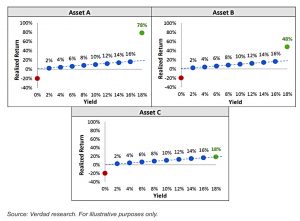

Brian and Nick look at three assets:

- Asset A delivers large positive surprises when yields are high (ie. prices are low)

- Asset B delivers a moderate positive surprise

- Asset C delivers no positive surprise.

When expensive (0% yield) they each deliver the same negative surprise.

- And they all perform the same when yields are in the 2% to 16% range.

So Asset A is the most attractive.

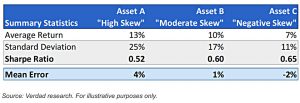

But although A has the highest return, it also has the highest standard deviation, so it has the lowest Sharpe ratio.

- The mean error is a better measure since this is positive for A and negative for C.

A has one positive surprise of +60%, one negative surprise of -20% and eight conditions with zero surprise.

- So using mean error would push you towards the asset wit the highest returns.

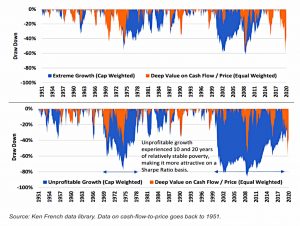

Brian and Nick note that value stocks have behaved like Asset A (higher returns, lower SR, better mean error) and growth stocks have behaved like Asset C.

Drawdowns also look better for value, though it should be noted that growth has been measured on a market cap basis, and value on an equal-weight basis (to reflect common investor practices).

- The whipsaws in value’s drawdowns lead to a higher SD, and a lower SR.

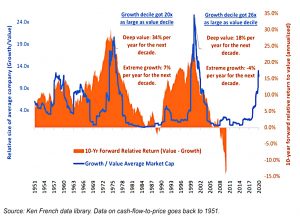

Brian and Nick note that the lost decades for growth stocks were preceded by very high valuations.

The decades of massive value outperformance (and growth famines) seem to have been presaged by the widest price divergences between growth and value.

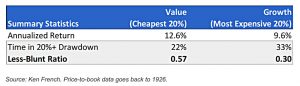

They propose a new “Less-Blunt” ratio which divides returns by the amount of time an investor would have spent in a 20%+ drawdown.

- This measure makes no assumption about the distribution of returns.

Not surprisingly given what we have seen so far, value comes out ahead.

Triple Lock

The Pensions Policy Institute has issued a briefing note which suggests adding a smoothing mechanism to the earnings portion of the Triple Lock on the State Pension.

- The issue that it’s trying to address is that the collapse in average earnings in 2020 (due to Covid-19 and the furlough arrangements) will be ignored by the current mechanism.

But a potentially significant rebound in earnings in 2021 would be captured and would lead to a big rise in the state pension.

The suggestion sounds reasonable at face value and is certainly preferable to scrapping the Triple Lock (keeping it is a Tory manifesto pledge).

- But I’m not a fan of tinkering with rules (and adding complexity) to deal with one-off and/or temporary issues.

Instead, I think we need to take a step back and think about why the lock exists.

- It’s there to prevent the State Pension from becoming a pitiful proportion of average earnings, as it did a few decades ago.

The last time I checked, the UK state pension was less than 30% of average earnings – the worst in the developed world – compared with an average across the OECD of more than 60%.

- Countries like Holland, Portugal, Italy and Austria all pay out more than 90% of average earnings.

So to prevent this issue arising before each year’s budget, it might be better to replace the triple lock with a target of say 50% of earnings, to be implemented over the next 10 years.

- But if the recent press coverage is indicative, people want to pay UK pensioners less, not more.

It’s the only part of the benefits system which doesn’t seem to be popular with the socialists.

Quick links

I have eight for you today:

- Philosophical Economics (guesting at OSAM) took a (very long) look at Upside-Down Markets

- UK Value Investor sold Xaar after concluding that heavy R&D and cyclicality are not a good mix

- The Guardian reported that David Beckham will be floating his e-sports team on the LSE

- The Economist wondered whether Netflix’s culture of innovation could survive further growth

- And warned us to beware the power of retail investors

- Alpha Architect looked into whether we can use the Shiller CAPE ratio to forecast country returns

- The Escape Artist reminded us that when you want to help someone, you tell them the truth

- And Disciplined Systematic Global Macro Views pointed out that smart beta ETFs are not so smart after launch.

Until next time.

Every two years the OECD publishes “Pensions at a Glance”.

See https://www.oecd.org/publications/oecd-pensions-at-a-glance-19991363.htm

for the latest issue – and a downloadable PDF too.

Figure 1.13 therein captures your 30% point rather well.

Thanks for that link – I’ve never seen the source document before.

No worries.

IMO, the report contains a lot of good stuff and is particularly worth reading because it sets things in a wider context.