Weekly Roundup, 15th March 2016

In the run-up to this week’s Budget, we start today’s Weekly Roundup with Tim Harford in the FT, who was looking at the UK’s sin taxes.

Contents

Sin taxes

Tim thinks it might be time to change the way we tax sin.

It’s a good idea to tax products that are:

- price insensitive (ie. people are addicted to them)

- socially harmful

- environmentally harmful (eg. CO2 emissions)

- or physically unhealthy.

Hence our long-standing taxes (we normally call them duties to make them sound less painful) on tobacco (health), alcohol (social harm and health), driving and flying (CO2) and gambling (social harm).

It’s worth noting that sin taxes as a proportion of GDP have fallen from 4.1% in the early 1980s to 2.6% in 2015.

- duty on fuel and alcohol is down in real terms

- consumption of alcohol and tobacco is also down

Raising the duties beyond a certain point just directs consumption to smugglers and bootleggers.

- So perhaps we need some extra taxes.

What Tim doesn’t like about the system is the way that the taxes are levied.

- unhealthy things like bacon, butter, sugar are treated favourably (no VAT, compared with the standard 20%)

- heating and lighting for houses attract only 5% VAT, despite the CO2 emissions

- road tax (vehicle excise duty) is a tax on owning a car (no impact) rather than driving it (CO2 emissions)

- and alcohol has a different tax for every kind of drink

Tim would like to see a level playing field:

- a tax per unit of alcohol

- a tax per unit of CO2 (a carbon tax)

- a new tax on sugar

- congestion charging for traffic outside London

Tim is also unhappy about the “Jaffa Cake” problem:

- cakes have zero VAT

- biscuits have 20% VAT

Back in 1991, a tribunal ruled that Jaffa cakes are cakes – even though they are sold as biscuits – because they start off soft and go hard when stale.

- better to have 20% VAT on both cakes and biscuits

- better still to tax by the sugar content

It’s hard to argue with Tim’s suggestions, but we seem to have a problem in the UK with publicly stating that certain behaviours are undesirable and will be “punished”.

- This is particularly the case when the behaviours (eg. junk food) are concentrated in a subset of the population (eg. poor people).

I think (like Tim) that we need to get over this.

- Keeping bad things cheap because they are popular with the poor makes no sense whatsoever.

Dividend taxes

Keeping with the Budget theme, Adam Palin looked at the impacts of the new tax regime for dividends, which was announced in a previous budget but comes into force next month.

The dividend allowances is a first, and the government has stated that “ordinary investors” won’t be worse off.

- Despite this, the measure is projected to raise £6.8 bn by 2020/21.

The good news is that dividends inside SIPPs and ISAs are not affected, so those people who mainly invest via tax-efficient wrappers won’t see much change.

For the rest, the first £5K of dividends are tax-free, but any further dividends attract a surcharge:

- 7.5% for basic rate (20%) taxpayers

- 32.5% for higher rate (40%) taxpayers

- 38.1% for additional rate (45%) taxpayers

This is a flat 7.5% increase from the tax paid this year.

The winners are higher earners with moderate dividend income.

- a higher rate taxpayer could earn up to £21,667 in dividends before paying more tax

Losers are basic rate taxpayers earning more than £5K in dividends (outside SIPPs and ISAs).

- they will pay tax where this year they didn’t

Even bigger losers are those paying themselves dividends from their own companies

- many who work through a personal service company are caught by the IR35 regulations, which impose a “deemed salary” for tax purposes

- but some industries are not covered, and these workers tend to pay themselves a low salary and lots of dividends

A business owner receiving £10.6K (the current tax-free allowance) as salary and £30K in dividends will pay an extra £1,875.

- but this is still cheaper than paying the £30K as more salary when employer’s and employee’s NI contributions would add another £7.3K

It should also be noted that the dividend allowance is not really an allowance:

- it’s a zero rate band

- dividends within it count as taxable earnings and push your other earnings into higher bands

For example, a pensioner “earning” £11K would pay no tax next year.

- But if they also had £5K of dividend income, they would pay 20% tax on £5K of their other earnings

- So they would be worse off than at present, despite the new “allowance”

US election

Ken Fisher reassured us that the US election – amongst other things – is nothing to worry about.

Markets hate uncertainty – including the potential impacts of negative interest rates and a possible Brexit, never mind weak US earnings and the US election – but it doesn’t last forever.

- Ken says that the president, in particular, has limited power and less impact than most people think.

When the uncertainty ends, stocks tend to recover, and Ken expects this to happen later in 2016.

- So get in now before it happens.

If you need cheering up, read Ken’s article in full.

Limits of central bank action

John Authers wrote about the limits of central bank action.

- The latest piece of envelope-pushing came from the ECB, but it produced the opposite reaction to what might have been expected.

Mario Draghi surprised the markets with a three-pronged attack:

- increased asset purchases (QE), including corporate bonds for the first time

- the idea is to push up asset prices, creating a “wealth effect” where people holding the assets feel able to buy more stuff

- interest rates (already negative) cut even further

- new loans to banks, reducing their borrowing costs

- unprofitable and / or heavily indebted banks are unlikely to make the loans needed to boost growth

The problem is that markets react to the future, and one of the key weapons for central banks is to manage future expectations.

- here Draghi made a mistake, saying he didn’t expect lower rates in the future.

- the euro fell at first (after the initial announcement) then rose sharply after Draghi’s comments

The same thing happened when the Bank of Japan brought in negative rates in January.

- the yen should have fallen, but it went up

John believes we are now reaching the limits of central banks’ power.

- the QE “wealth effect” has worked outside the US, and only to a limited extent there

- adding new assets to the purchase programme just highlights that there aren’t enough of the original assets left to buy

- and negative rates impact bank profits, making them less likely to lend; propping banks up with new loans probably won’t fix this

John quotes a new book by Mohamed El-Erian, one of my favourite investors – The Only Game in Town.

[amazon template=thumbnail&asin=030022253X]

El-Erian calls this situation a “T-junction”:

- either the economy sparks back into life or the problems of 2008 return

- new fiscal policy and structural reforms are needed (John doesn’t go into detail on what these are)

John (and El-Erian) recommend holding cash in case the worst happens.

For John, another reason to hold cash is that the US bull market in stocks just celebrated its seventh birthday.

- US stocks are expensive and their earnings are deteriorating

All in all, a nice counterpoint to Ken’s optimism.

British Euro-scepticism

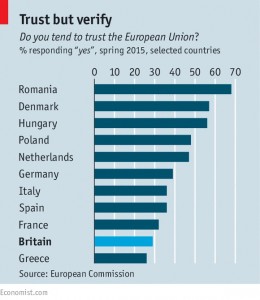

As part of its weekly series of Brexit briefings, The Economist looked at why Britons don’t trust the EU.

The EU grew from a reconciliation pact between France and Germany, the European Coal and Steel Community (1951, from 1957 the European Economic Community).

- Britain preferred to maintain links with the US and the Commonwealth until the 1960s when the EEC’s economy was stronger than ours.

- For those too young to remember, we joined in 1973.

- Britain’s identity is built around rebuffing threats from across the Channel.

So we have a transactional relationship with the EU

- We evaluate the costs of membership with the benefits (basically free trade).

- Arriving late, we found a lot of the pre-existing rules not to our taste.

Initially, Labour was the sceptical party.

- Then in 1988 Jacques “Up Yours” Delors promised tougher labour and social regulations, and plans for closer EU integration and a single currency.

- From then on the Tories were anti-Europe.

- After 2010, new prime minister Cameron also had to deal with UKIP.

So he promised a renegotiation and a referendum, just as Harold Wilson did 40 years earlier.

US frackers

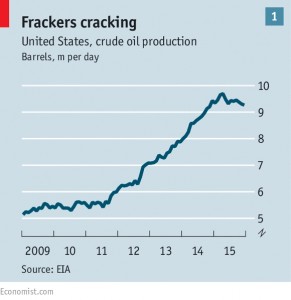

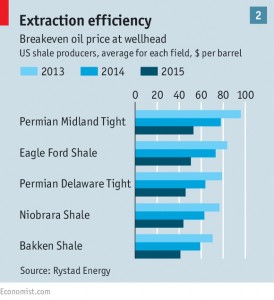

The newspaper also looked at the prospects for US fracking companies.

- US oil production in December – 9.3M barrels a day (Mbd) – was lower than a year earlier for the first time since early 2011.

- The Energy Information Administration (EIA – part of the US government) expects production to fall to 8 Mbd by later 2017.

As oil prices edged back from $30 towards $40 a barrel some in the industry predicted a turnaround in production (which would, in turn, cap an oil price recovery).

- There seem to be wells that are viable at $40-45 a barrel, and in theory, it is not hard for frackers to increase production rapidly.

- Firms have laid off workers, but the pay is good and they should be tempted back.

- The key factor is the “drilled but uncompleted” (DUC) wells, ready to be exploited once the price is right.

The problem is likely to be finding the cash to start them up.

- For years the industry had to borrow to increase production as cash generation from existing wells was inadequate.

- Now there is little money available, and it is much more expensive.

And the books are still not balanced:

- In 4Q2015, American and Canadian oil firms spent $20 bn to generate $13 bn of cash flow

The next stage is more likely to be a wave of bond defaults and company failures.

- The frackers probably need $60 a barrel to be restored to health, and that looks a long way away right now.

US inflation

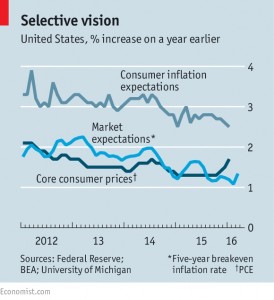

A third article in The Economist looked at US inflation.

- It’s going up, but not everybody has noticed because of conflicting signals.

When the Fed raised rates in December, prices were rising by just 0.5% pa.

- But a healthy labour market suggested inflation was on the way, and raising early might head off the need to raise abruptly later on.

Since the raise stock markets are down, but the labour market is still strong.

- And core inflation (which excludes food and energy) was 1.7% in January.

But consumers are only forecasting inflation of 2.5%.

- That’s 0.5% below their long-term average, and the lowest since 2010.

This may just be a late adaptation to cheap oil and a strong dollar.

- But inflation expectations in financial markets also remain depressed.

The difference between yields on inflation-proof government bonds and the vanilla flavour suggest inflation of 1.4% over the next five years.

- The Fed thinks that the bond spread is compressed because linkers are less liquid these days, and investors want a higher return to risk holding them.

But the swaps market is pointing to medium-term inflation of around 1.7%.

- And consumer spending remains strong.

Against this confused picture, the Fed is likely this month to raise its inflation forecasts even as it postpones rate rises.

- But a climb in the oil price or a fall in the dollar would put multiple rate rises back on the table.

High tech low finance

Buttonwood looked at why a high spend on technology has not made finance efficient.

- Money is just a number in a computer these days, and it ought to be cheap and easy to move around the world.

- Similarly, stock trading is dominated by computer-driven high-frequency trading.

And the finance sector has the highest spend as a proportion of revenues on information technology of any industry.

Despite this, it took years to move from “T+2” settlement (two days after the date of the trade) from “T+3”.

Payments currently travel through many hands on their way from payer to recipient, and the industry creams off $1.7 trn for making this happen.

- The basic problem is that banking goes back a long way, and technology has been largely used to speed up existing systems by replicating them, rather than by coming up with something new entirely.

And now the early systems are decades old, a lot of the technology spend goes on maintaining them.

“Fintech” – which covers digital payments to robo-investment advisors – offers a new hope to some.

- The blockchain technology behind Bitcoin – essentially a distributed ledger of transactions – has the most buzz.

In theory, it would be more secure as tampering with it requires access to all members records simultaneously.

- But at the moment, blockchain can’t handle the thousands of transactions per second that the big credit card systems are capable of.

And there is a fundamental conflict between the interests of customers – who want an open, cheap and anonymous system – and of governments and regulators – who want to snoop for tax evasion and money laundering.

Progress will probably be slow though a continued move to negative interest rates might drive more people into the arms of Bitcoin.

Forecasting growth

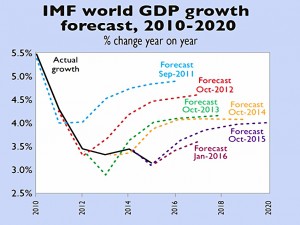

We normally begin this weekly column with a chart, but today we end with one.

It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future. – Yogi Berra

Here’s the IMF proving him right with its world GDP growth forecasts, courtesy of MoneyWeek.

Until next time.

On the sugar tax thing, I would say that the idea is (or should be) to nudge manufacturers towards substituting sugar with an alternative (e.g. replace sugar in chocolate bars with splenda), rather than to nudge consumers towards alternative foods (e.g. replacing chocolate bars with apples).

It’s a bit like the new car tax, which is CO2-based. The idea is mostly about nudging manufacturers to make their cars more fuel efficient (e.g. making a more efficient Mondeo) rather than influencing consumer’s to buy different cars (e.g. switching from a Mondeo to a Fiesta).

I see where you’re coming from, but I’d rather people ate apples and drove Fiestas.

I think we go too far as a society in pretending that all behaviour is equally acceptable.