Weekly Roundup, 8th March 2016

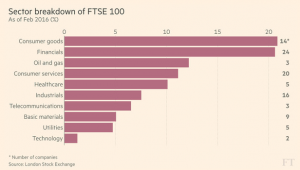

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with the Chart That Tells A Story. This week the column was about FTSE 100 sectors.

Contents

FTSE 100 sectors

Naomi Rovnick reported that consumer stocks have taken over from financial services as the largest sector in the FTSE 100.

- Back in 1984 when the FTSE 100 was launched, a lot of the original members were UK manufacturers.

- But these days the FTSE 100 is much more international, with lots of overseas earnings and plenty from emerging markets.

- But this is as true of consumer groups as it is of mining and energy stocks.

- Unilever made 58% of sales in the developing world and the largest contributor to BAT’s cigarette sales was “eastern Europe, the Middle East and Africa”.

Banks and asset managers are under regulatory pressure to reduce fees and become more transparent.

- They also don’t pay the generous dividends that they used to, as profits have been squeezed by the low-interest rate environment.

- A lot of the banks now trade at below net asset value, which means that investors think that value will be written down in the future.

Brexit

There was more on Brexit this week, with Merryn giving her reasons why UK investors should vote Leave.

- The EU “doesn’t exist”.

- It isn’t Europe – which is real; it is an “imagined community”.

- Most of us feel no real connection with it.

- We care only about what we can get out of it.

- Lack of democracy.

- Representation to the bodies that govern the EU work too indirectly.

- Our PM has to ask 27 other people before he can make minor changes to our welfare system.

- The economy.

- It’s easier to measure potential loss than gain.

- Big UK companies lobbying hard against Brexit have spent decades and fortunes to create an environment that works for them.

- But Brexit is not a leap from the light to the dark but from greyish to more greyish.

- Scotland.

- Merryn thinks that Brexit is the best chance to save the union.

- I think the opposite, but then I don’t want to save the union, so this doesn’t put me off Brexit.

- She does have a good point that Scotland may not vote to leave while the oil price is so low.

The Economist wrote about how hard it is to get unbiased information about the key issues.

They provided three examples:

- 3m jobs in Britain depend on trade with the EU

- The true figure is probably higher, but the idea that all these jobs would be at risk post-Brexit is nonsense.

- Job creation depends on demand, wage levels and labour laws more than on membership of a trade block.

- The British contribution to the EU budget.

- Leavers claim we pay £20 bn

- This ignores the Thatcher rebate and the money the EU spends in Britain

- The next payment is only one-third the size, and Britain is only the eighth-largest contributor per head

- Trade patterns.

- Remain campaigners say the EU takes 45-50% of British exports, whereas Britain accounts for less than 10% of the EU’s

- There are problems here with competing sources of data, whether services should be included as well as goods, and whether the EU should be seen as a block, discounting all intra-EU trade

- Britain takes 16% of block-EU exports, but only 8% of all individual members’ exports

Though pro-staying in itself, the newspaper recommends several websites for better information:

- the broadly neutral fullfact.org

– the pro-EU infacts.org

– The UK in a Changing Europe

ISA season

ISA season is upon us ((Not for me – I invest in April, to get an extra year of gains )) and Aime Williams took a look at the new “Innovative Finance ISAs” – Peer-to-peer (P2P) lending to you and me.

P2P started in the UK in 2005 and is now a £3.2 bn industry.

- From April, you can take out an ISA with one of the popular platforms.

- You can even transfer old cash or stocks and shares ISAs into the new IF-ISA.

- But you can only have one IF-ISA on one P2P platform per year, so setting up a diversified portfolio would require something in the region of £75K.

I got involved right at the start but stopped lending when the credit crunch hit in 2008.

- I took the last of my cash out of my account a few weeks ago.

But the low-interest rate environment since the 2008 crisis means that P2P’s higher interest rates (average 5.1% at the moment) have looked very attractive to many savers, and the industry has boomed.

The logic of P2P lending is attractive – borrowers and lenders are matched online, cutting out the expensive middleman (the banks).

But it’s a lot riskier than cash:

- it’s not covered by the UK’s £75K deposit insurance scheme

- as the industry grows, the likelihood that borrowers who are poor credit risks will be drawn into the system increases

- so does the risk that the best borrowers will be cherry-picked by institutional lenders (who now account for 25% of UK P2P lending)

- the next recession or an eventual increase in the UK’s interest rates could see default rates – which are currently low – begin to soar (industry insiders claim their stress-testing shows that things would be ok)

- and as the industry eventually consolidates around a few platforms, some of the weaker ones could go bust

Here’s a run-down of the main players:

- Zopa, the oldest platform, lends only to retail borrowers

- Funding Circle is 50% institutional money and lends only to small businesses

- RateSetter lends to a mixture of retail borrowers, small businesses, and property developers

- Landbay offers P2P residential (buy-to-let) mortgages

- ThinCats makes secured business loans to UK companies

- Lending Works has insurance against the risk of borrower default

- LendInvest offers short-term property loans

- MarketInvoice allows businesses who want money immediately to sell unpaid invoices to investors

If you do fancy an IF-IFA, look for a member of the Peer-to-Peer Finance Association (P2PFA), whose rules increase transparency:

- members publish bad debt rates and five years of credit performance, returns performance, and data about borrowers and lenders

- the P2PFA also has a rule against institutional cherry-picking

The IF-ISA could be a good thing for the sophisticated investor, but I worry that it’s exactly the unsophisticated who will be drawn to it.

- The tax break on interest is welcome, but it really needs a third-party platform (Hargreaves Lansdown, or YouInvest) to offer loans from all the P2P lenders for the product to be really attractive.

For now, holding the P2P investment trusts in your SIPP or ISA looks like a better bet.

Over in Money Week, Cris Sholto Heaton had a few ideas on how ISAs could be made better:

- Let investors hold foreign currency, to support investing in foreign stocks

- Allow contributions to multiple stocks and shares ISAs within a single tax year

- Allow existing holdings (of shares) to be transferred directly into ISAs, saving two sets of dealing costs

They all sound like good ideas to me.

Pensions and the Budget

One of the most surprising pieces of news over the weekend was George Osborne’s decision to drop his plans to cut pension tax relief in next week’s Budget.

- The briefing stressed the dropping of the Pension ISA plan rather than the flat rate relief option, but now neither will go ahead.

I do think that a Pension ISA would have meant the end of pension contributions by most people, but I can’t see the problem with a flat rate of 25% or 30% relief.

- Presumably, the looming Brexit vote had something to do with it.

Commentators noted that uncertainty about the loss of future relief meant that a lot of cash had already been put into pensions by high earners, potentially losing the Treasury £1.5 bn in tax.

Leisure time

Tim Harford took a look at John Maynard Keynes’ famous statement – in his 1930 essay Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren – that “Three hours a day is quite enough.”

- Keynes was predicting that by 2030 advanced economies could be eight times richer, and able to afford a 15-hour working week.

In some ways, Keynes was right:

- we now enter the workforce later, after lots of study

- we have longer retirements since we live longer

- the work week has shrunk – from 69 hours in 1830 to 47 hours in 1930 to 39 hours by 1970

But around 1970, the work week stopped shrinking.

Part of the problem is the consumer society:

- Advertisers persuade most of us that more work means a better car and a nicer kitchen than the Joneses.

- And we all measure our success in relative rather than absolute terms.

The other side of the equation is income:

- In the US, national growth in GDP continued until the 2007 crisis

- But median household incomes began to stall around 1970

The divergence is partly driven by rising healthcare costs, and partly by the highest earners taking a bigger slice of the pie.

This explanation works for the average workers, but why are the rich still working so hard?

- It seems that success requires long hours

- And the stakes are high, with annual rewards at the top equal to many years of average earnings

One side effect is the resurgence of city centres, where nobody wanted to live until the 1980s.

- Now rich people don’t have time to commute, and they’d rather live near work.

- But all the rich people are chasing a few places to live, so in order to get their hands on one of them, they need to work even harder.

Three hours a day is never going to be enough, so long as someone else can work four, or fourteen.

Investment management

Buttonwood looked at the history of investment, which dates back to 2000 BC when landowners in Mesopotamia hired managers to look after their farms.

- Investment: A History by Norton Reamer and Jesse Downing looks at how the industry has developed.

[amazon template=thumbnail&asin=0231169523]

The basic trend is democratisation, with investment now available to many more people.

- in developed countries, many people have (or should have) some money available for savings after paying for food, clothing and shelter

- and by retiring at around 65, they have two decades of old age to provide for

In the US, retirement savings grew from $368 bn in 1974 to $22 trn in 2014, a 500% increase relative to income.

The industry has also managed to become glamorous, where it once was dull.

- partly this is to do with the development of more products and tax shelters

- but mostly it’s to do with the massive increase in fees

Since fees are usually linked to the value of assets under management (despite underlying costs not rising in this way) the profits available are now huge.

- In ancient times, the poor looked after the assets of the rich, but now it’s the other way round.

Emerging markets

John Authers looked at the prospects for emerging markets (EMs), which have been in a bear market for five years.

He wondered whether the detention of Brazil’s former president Luiz da Silva could be the “blood in the streets” moment – a catharsis that marks the bottom.

- Certainly Brazil’s currency and stock market rebounded, sending a ripple to other EMs.

John looked at a new book by Antoine van Agtmael, who coined the term “emerging markets” back in the 1980s.

- The book is called The Smartest Places on Earth and suggests that the future belongs to the old “Rust Belts” of the developed world.

- These are often hotbeds of innovation and growth, built around a great historic university.

[amazon template=thumbnail&asin=1610394356]

Two things have changed for EMs:

- globalisation may not be irreversible, at least in terms of the physical movement of goods around the world

- global trade is growing more slowly than at any point since 2009

- cheap labour may not be an enduring competitive advantage

- smart labour is now more important than cheap labour

So buying EMs is not about dynamism and growth.

- But it could be about things being too cheap.

Compared to the US, prices look sensible.

- And EM currencies are rising

- So are industrial metals

- And now EM stocks are starting to move

Emerging market debt

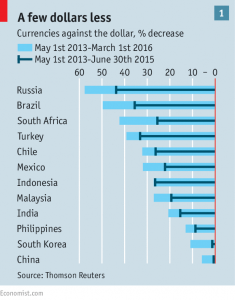

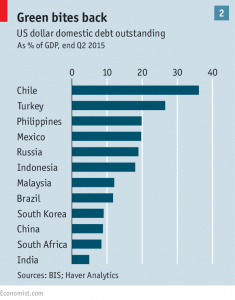

The Economist looked at emerging market (EM) debt, and the importance of borrowing in dollars to the business cycle in developing countries.

- Corporate debt in 12 biggish emerging markets rose from 60% of GDP in 2008 to more than 100% in 2015.

- Resources firms, in particular, are struggling with the rising cost of servicing dollar debts taken out when the dollar was much weaker.

The Bank of International Settlements (BIS) says that the global liquidity cycle in dollar borrowing outside America explains the slowdown in EM economies, the rise in the dollar, and the oil glut.

- When the dollar was weak and global liquidity was good (because of the Fed buying Treasuries under QE) companies outside the US found it cheaper to borrow in dollars.

- These capital inflows pushed up local asset prices, including currencies, making dollar debt even cheaper.

- This feedback loop continued until the dollar started to strengthen (as QE was phased out and bond buying ended).

Where there has been lots of borrowing in a foreign currency, the exchange rate becomes a financial amplifier.

- As companies rush to pay down their dollar debts, EM asset prices fall.

- Firms cut back on investment, sack employees, and GDP falters.

- This drives down EM currencies, turning the virtuous circle into a vicious one.

- The indebted oil firms must pump as much as possible to pay down their loans, leading to a supply glut.

But perhaps the BIS overstates the case:

- Rich countries that export raw materials (Australia, Canada and Norway) have also seen their currencies fall against the dollar as export income falls.

- And the average dollar share of corporate debt in EMs is ony 10%, with a quarter of the total in China.

- Since August, when it seemed likely the yuan would be devalued, dollar loans have been swapped into yuan.

- And much of the dollar debt is long-term (10 years or more), with refinancing and the risk of default far in the future.

- And dollar debt is usually matched by dollar income, even if it is falling.

A more worrying side of the dollar lending cycle is the finding that EM firms with cash were more likely to issue dollar bonds.

- Cash and debt together are usually a red flag in corporate accounts, but it appears that the borrowing was driven by speculation.

- Companies were acting as surrogate financial firms, borrowing to buy other firms’ commercial paper or even to lend to them directly.

- Thus dollar borrowing leads to easier credit conditions in Ems.

Now that dollar lending has peaked, tight financial conditions are expected in EMs.

Until next time.