Weekly Roundup, 1st May 2018

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with Merryn Somerset Webb. This week she was looking at the struggles of fund managers to be average.

Contents

Aiming for average

Merryn has been reading a book about the origins of asset management.

- Investment trusts were the start, emerging in the 1800s to offer an alternative to falling government bond yields through the nineteenth century.

It’s interesting to note that initially both the investors and the managers came from a wide variety of social backgrounds.

The other big contrast to today is the long-term, global orientation and the lack of restrictions on what they could invest in.

- These days managers are mostly niche, restricted by tight investment policies and focused on their quarterly performance against the benchmark and their peers.

Fees have also risen since the 1800s, when 0.25% pa was common.

Merryn also quotes a new paper which highlights the dangers to fund manager careers if they underperform their benchmark.

- She points out that outperformance cannot come without the risk of underperformance.

It’s the fear of underperformance which leads to the prevalence of closet trackers.

Tim Harford wanted to put a price on Facebook, email and search.

A new paper suggests that US users of Facebook would need $38 to $48 per month to give up Facebook.

- 20% of users would give up for as little as a dollar per month.

Internet search is apparently worth $17.5K pa, email $8.5K pa and online maps $3.5K.

- Video streaming (Netflix and YouTube) is worth $1.2K pa, online shopping $850 pa and social media just $300 pa.

As Tim says, the numbers vary from survey to survey, but the relative rankings are pretty clear.

- Search, email and maps are “digital necessities”.

- Video, shopping and social media are luxuries.

When things that are cheap (or free) provide a great benefit to people, this is known as the consumer surplus.

- The best example is the indoor toilet, which is valued much more than anything on the internet.

I would add electricity, running water and central heating to my personal list.

- I’m sure others would lobby for TV, the phone and cheap private cars.

The question is whether the internet age has a much bigger consumer surplus than previous eras.

- It would appear that the surplus is at a new peak, but the rise from 1900 to 1990 is probably more significant.

Bringing it back to stocks and economics, Tim asks why Google (search) and Microsoft (email) are not worth much more than Facebook (social media).

- He suggests that it’s down to monopoly power, or the network effect – all your friends are on Facebook, so there is no alternative.

- That makes it easier to turn a profit.

There are certainly plenty of email systems, and they all play nicely together, but isn’t search basically a Google monopoly?

Tim wants to make social media more like email, and points us towards a new system called Solid from Tim Berners-Lee.

- Good luck to him, but when market leaders are as entrenched as Facebook, it usually needs a serious change in the landscape to disrupt them.

Foxes and hedgehogs

Maike Currie was channeling Archilochus in her classification of investors:

A fox knows many things but a hedgehog knows one big thing.

The concept is that hedgehogs view the world through a single big idea, while foxes draw on many sources.

Within the investment realm, it’s much easier to market a hedgehog.

- The story is clear and there’s usually a (recent) good track record.

But everything goes in cycles, and no single big idea works all the time.

As you will have guessed by now, I’m a fox – I use multiple strategies in an attempt to avoid years of catastrophic underperformance (which I think are extremely damaging in the long run).

- I think this flexibility is one of the key advantages that private investors have over the professionals.

But it’s certainly not an easy message to get across to people.

Inheritance tax

In a couple of articles, Kate Beioley and Lucy Warwick-Ching took a look at the new consultation on inheritance tax.

- The Office of Tax Simplification (OTS – not the most conspicuously successful body in Britain) will allow tax advisers and the general public to have their say.

There’s a 10-minute online survey on the complexity of the current rules, and the forms you need to fill in when somebody dies.

- The consultation closes on June 8th, and a report is due in the autumn.

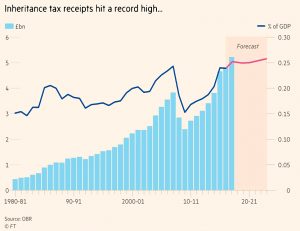

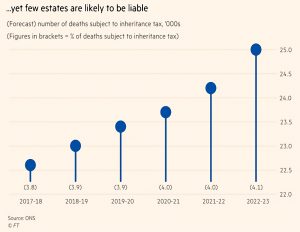

The IHT take just hit a record £5.2bn, as rising house prices in the south have dragged more families into the net.

- The £325K basic exemption (there’s also a property exemption of £125K) has not been increased since 2009/10.

- The £5.2 bn was paid by just 25,000 families.

The other key exemption is business property relief (BPR) which originally exempted family farms and businesses (to avoid them having to be split up) but which now also includes AIM shares that have been owned for two years or more.

- There are also trusts, but the rules here are becoming more complex and the tax savings much smaller.

I don’t like inheritance tax.

- It seems progressive because only the top 5% of estates pay it.

- But really it’s double taxation – those who spend their money as they earn it can’t pay IHT, but those who prudently save and invest can.

There’s no need for taxes beyond:

- the point of receipt (income tax)

- the point of consumption (VAT)

The only other taxes should be “sin” taxes on things we want people to avoid.

- So the message from IHT is don’t amass more than £425K during your lifetime.

I think the allowance should be much higher, to reflect how much capital is needed to live a comfortable life in the south of the country.

- The exemption in the US is $5M.

We could also do with a much higher annual gift allowance (£3K pa at the moment) to encourage passing wealth down the generations.

- Fat chance of either of those reforms being what we see in the autumn.

Reality distortion

John Authers looked at the difference between reality and perception.

- In the short run, perceptions drive the markets, not reality.

John’s point is that ten years of QE and low interest rates mean that we have more distortion to cope with than usual.

US corporate earnings so far are excellent – on track for a 25% increase on last year.

- Over in Europe, the Stoxx 500 is on track for a 1% increase.

But US stocks are down for the year, and European stocks are outperforming them.

- Don’t US investors believe the numbers?

In bonds, the 10-year just broke through 3% yield, but the 30-year is lower than it was four years ago.

- Inflation breakevens suggest 10 year inflation below 2.2% pa.

- And the yield curve remains flat, suggesting sluggish future growth.

Core inflation is also low (1.7% in the US).

- But growth is at 2.3% and employment costs are rising at 2.7% pa.

So markets simultaneously expect improvement and decline, inflation or no inflation.

- John suspects that we won’t have clarity until the inflation path resolves itself.

Fintech fixes flaws

In the Economist, Buttonwood looked at how financial technology could be used to fix investors’ flaws.

- Lower trading costs, and easy diversification through cheap index trackers have already greatly helped the private investor.

But they also encourage over-trading.

Buttonwood would like to see technology used in a different way:

- To help people work out how much they need to save

- the median balance in a US pension plan owned by someone aged between 40 and 55 is $14.5K

- low interest rates (designed to discourage saving) mean than people need to save more than ever (since returns are lower)

- statistical models of longevity, inflation and future returns can help people save the right amount

- To choose strategies that don’t need a lot of trades

- the two traps are (1) to stick with the first asset allocation you came up with in your twenties, or (2) to endlessly fiddle

- hot sectors should be avoided, as they have probably already risem

- Buttonwood want automatic rebalancing to a high-level asset allocation (as per some funds offered by firms like Vanguard)

- Rebalancing helps by selling high and buying lower.

I think the second point is being addressed by ETF providers and robo advisors.

The first is more difficult:

- Lots of people can’t understand (and therefor trust) these models.

- And when they spit out the answer that people need to save three times as much as they currently manage, investors are more likely to give up in disgust than to mend their ways.

Crypto regulation

The Economist also had a leader article on how to regulate crypto-assets.

They say there are three questions to answer:

What are crypto-assets?

How should day-to-day risks be managed?

And what threat do they pose to financial stability?

Authorities variously classify crypto-assets as commodities, currencies, securities and a separate asset class.

- The Economist likes the Swiss approach of basing treatment on function (are they used for payments, access to a service, or as investments).

Day-today risks centre mostly around criminals.

- Money-laundering regulations need to be extended into the “crtypto-sphere”.

- The exchanges where regular money is swapped for crypto should be targeted.

- The newspaper sees no need for restricting access to crypto-assets to accredited investors.

The risks to the system are low, as crypto is worth only 3% of the balance sheets of the main four central banks.

- But given the recent wild fluctuations in value, regulators need to keeps their eyes open.

Basic income

The Economist also reported that Finland’s trial of basic income will not be extended when it closes in December 2018.

We’ve looked at basic income several time before.

- It’s an interesting idea, but impossibly expensive to implement in a country like Britain, with the burden falling heavily on those in the £25K to £85K pa income bracket.

There are plenty of other trials, though most do not used randomised control group procedures, and those that do will not report for years to come.

Book value

In MoneyWeek, John Stepek argued that book value may not be as useful an indicator as it once was.

- Book value is the net worth of a company’s assets, minus its liabilities.

- It’s normally compared to the share price (market cap).

Anything trading at a P/B of less than 1 could be a bargain.

A new paper reports that recently, companies with negative book value, and those with high P/Bs (but other measures indicating that they are cheap) have outperformed.

There are two explanations:

- intangibles (eg. brands) are often under-valued on balance sheets

- long-term asset like property are often listed at less than market value

Share buybacks shrink the balance sheet further.

Safe withdrawal rate

In FT Adviser, Maria Espadinha reported that The Institute and Faculty of Actuaries has chosen 3.5% pa as a safe withdrawal rate (SWR) for those in drawdown.

- This assumed drawdown started at age 65.

- If you start drawdown at age 55, 3% is your SWR.

The classic “4% rule” comes from research in the US in the 1990s, and many in the UK have advocated using a lower rate for the here and now.

Of course, your personal rate will depend on life expectancy and the asset allocation of your investments, but it’s good to see an official proclamation that doesn’t say 4% pa.

Twitter pics

I have five for you this week.

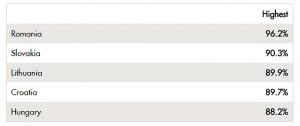

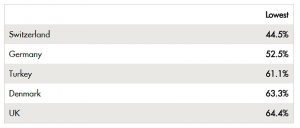

There was a lot of talk in the papers that many millenials will have to rent forever.

- It’s certainly true that the UK is dropping down the league table of home ownership.

The highest rates are now all in eastern Europe.

Whereas the lowest rates are largely in the northern, Germanic states.

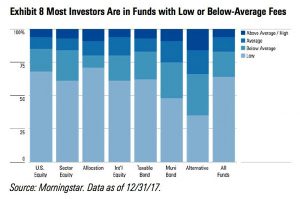

This chart shows that most investors (presumably in the US) have moved across to low-cost funds.

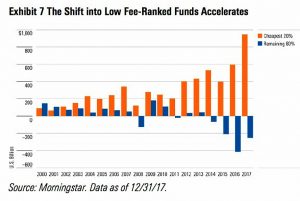

And this one shows that the trend is accelerating.

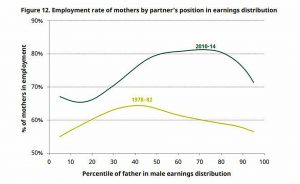

Finally, this chart shows that the proportion of mothers working – which thirty years ago used to be highest in the working class – now peaks amongst the middle classes.

- I’ll hazard a guess that the cost of childcare (and the loss of family networks able to provide free childcare) has something to do with this trend.

Until next time.