Weekly Roundup, 25th August 2015

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup in the FT, with the Chart That Tells a Story.

Contents

FTSE 100 falls

In Saturday’s edition of the newspaper, Lucy Warwick Ching took a look at the recent decline in the FTSE 100.

The FTSE 100 index fell 5.5% last week to close at 6,188 on Friday – its lowest since December 2014 – including a big one-day fall.

Since then we’ve had a 4.7% crash on Monday, followed by a recovery on Tuesday morning (as I write) to 6,050.

The index is down a long way from the 7,000+ of May, and is now in official “correction” territory (down more than 10% from its peak).

The FSTE managed to cope with the Greek crisis and the oil price, but the Chinese devaluation of the renminbi and the implied slowdown of the Chinese economy – with further knock-on effects for commodities – has tipped it over the edge.

The looming US interest rate rise was also felt to be a factor initially, but by Monday night the first analysts were suggesting that further QE was more likely than a rate rise.

The FTSE is an interesting index because of its global exposure, but the over-reliance on oil and mining stocks (around 20%) makes it extra vulnerable to a crisis like this.

It’s also a good reason to avoid trackers that follow the index. A selection of equal weight individual shares from the FTSE will mostly likely have outperformed over the last three months, as would many active funds and investment trusts.

Other UK stocks that will be hit by a Chinese slowdown include Burberry. Its share price is down more than 30% since March.

The FTSE 250 is more of an UK index with less exposure to emerging markets, and so has fallen around 10% less than the FTSE 100 during 2015.

With more market panic possible, the important thing to remember is not to sell stocks after a sharp correction. This only increases the likelihood that you will miss the recovery.

Pensions

The FT had two articles about pensions. The first, by Judith Evans, was about how much is enough?

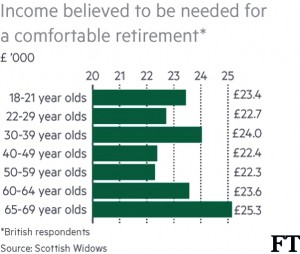

It was a fairly elementary discussion with lots of industry guff, but it included the chart below which shows general agreement across all age groups that around £23K pa is needed for a comfortable retirement.

The second article, by Josephine Cumbo and Claer Barret, was called Pensions — which way now? and looked at the options that might emerge from the government’s ongoing pensions review.

We’ve looked at this issue before, but the FT invited three industry “experts” to give their views.

The most radical option under consideration is the “pensions Isa”, where there is no tax relief on the way in, but withdrawals in retirement are tax-free.

This is a switch from the current EET (Exempt, Exempt, Taxed) system to TEE. The advantage of EET is that it incentivises people to save, but the disadvantage is that most of the benefits go to higher rate tax payers.

The advantage of TEE to the government is that it potentially brings forward tax revenues from the future.

There are two options in between the extremes:

- a flat rate of pension relief (say 30%) for all, under the existing EET system

- a TEE system with a government top-up (probably 20%)

Phil Loney, The CEO of Royal London warned recently that the pensions ISA could destroy the UK’s savings culture.

The time-table for any new changes is unknown, though a white paper – a specific policy proposal – at the 2016 Budget in the spring is most likely. Policy changes from April 2016 are also possible.

Michael Johnson, who we have met before, argued that the Pensions ISA would be “widely welcomed, particularly by Generation Y (the under 35s).”

Michael thinks that the underlying contract between savers and the government was that in return for tax relief you had to buy an annuity. With this gone, so should tax relief go.

I couldn’t agree less. The contract was “if you save, we’ll give you tax relief”, and this still holds.

Mandatory annuities were removed because low interest rates and increasing longevity made them poor value, not because people stopped saving up for them.

I can see an argument for flattening tax relief so as to incentivise more vulnerable groups, but scrapping it will just reduce the savings rate.

I suspect Michael is trying to drum up publicity for his “Lifetime ISA” concept, which would be part of auto-enrolment in workplace pensions.

At least he’s in favour of a government top-up – 50p per £1 saved, or 33% relief.

I doubt any general top-up would be this high as it wouldn’t increase the tax take, but Michael wants to cap the top-up at £4K pa, giving a max Lifetime ISA contribution of £12K per year, a massive drop from the current £40K pa.

That’s probably fine for regular savers if the existing £15K pa ISA remains, but it’s cutting things a but fine for those whose career earnings are “lumpy”.

Michael would lock away the money until retirement, and wants to see annuities as part of the decumulation phase. I can’t see them making a comeback myself.

John Ralfe was arguing for the flat rate relief, of 30%. He points out that “EET” is really “EEPT” (Exempt, Exempt, Partially Taxed) because of the 25% tax-free lump sum.

So 30% relief with a 25% tax free lump is a good deal for anyone with a retirement income in the 20% tax bracket (£43K pa now, rising to £50K pa by 2020).

Given that the lifetime pensions allowance is £1M (indexed from 2018), the maximum safe withdrawal is only £35K to £40K so the maths all checks out.

Anybody richer than this will have to fend for themselves outside the pension system (starting with ISAs). There’s more information on this topic here.

John quotes the behavioural studies that show people prefer a current reward over the promise of a future one, even if they have to give back the same value in the future (and are therefore no better off).

This supports my view that without tax relief or a top-up, savings will decline.

David Robbins argued for keeping the status quo.

- The key advantage of up-front relief is that you know you can’t be taxed twice on the same money.

- The second major advantage of the current system is that savings are locked away to age 55.

I think that the Pension ISA is probably on it’s way, but I hope that at least a 20% top-up is included.

And I hope any new system addresses the unfairness of public sector DB pensions, and their assessment under the lifetime allowance at 20 times income. ((Private sector DC pensions have an effective multiplier of 25 to 29, meaning that the lifetime allowance supports £35K to £40K of annual income, compared to the £50K of DB pension income that is allowed))

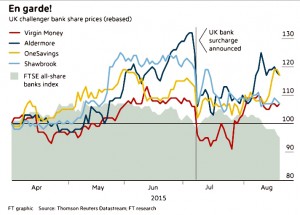

UK challenger banks

Lex wondered whether the UK’s challenger banks were just looking to be bought.

Barclays, HSBC, Lloyds, RBS and Santander have 85% of current accounts, but the Government hasn’t been able to introduce any large-scale competitors.

TSB (with 4.5% of accounts) is the closest thing to a disruptor, and is now part of the Spanish bank Sabadell.

The summer budget’s surprise 8% surcharge on bank profits above £25m – starting in 2016 – hasn’t helped.

Switching current accounts with overdrafts is hard, so Aldermore, OneSavings Bank, Shawbrook and Virgin Money stick to niches in mortgage and unsecured lending.

Despite this, the challengers all have higher ratings than the big banks. OneSavings trades at 3 times tangible book value.

Is this because the market expects them to be bought up like TSB?

Diet for growth

Tim Harford wrote about the role of finance in growth.

A larger financial sector has historically been seen as good news, but since the financial crisis, a few papers have suggested the opposite.

Tim quotes Sir David Hendry’s spoof 1980 correlation between consumer prices (inflation) with cumulative rainfall to wonder whether statistical manipulation is being used to confirm current prejudices (as suggested recently by William Cline).

Rich countries grow more slowly than poor ones, and have larger banking sectors. There’s the negative correlation.

But the same trick would show that doctors, telephones and R&D are bad for growth. Really it’s just that being rich already is bad for further growth.

Tim says that banking is a complex system, and needs to be broken down for analysis. Mortgages, payday loans, life insurance, credit derivatives, venture capital and equity tracker funds may have different effects on growth.

Christiane Kneer of DNB (the Dutch central bank) has looked at the idea that banking sucks talent away from the rest of the economy.

As the US states deregulated banking, skilled workers were hired from manufacturing, reducing productivity. This suggests that too much finance is bad for growth.

Stephen Cecchetti and Enisse Kharroubi argue that large banking sectors don’t fund the most productive investments, as they are supposed to.

They’s rather lend to businesses with collateral, especially mortgages against property. Intangible assets (including R&D) are less attractive.

So large banking sectors lead to lower growth in R&D intensive areas.

On the other hand, development economists have long observed that poor countries struggle to develop without decent banks to lend money to businesses.

Having more finance than the economy can use is specifically a first world problem.

Britain’s new underclass

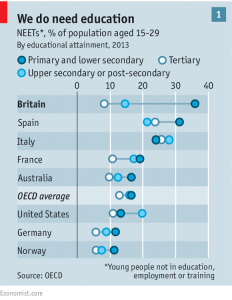

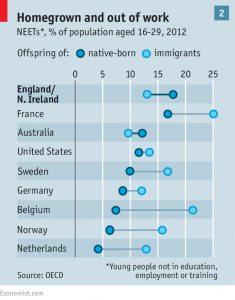

The Economist wrote about Britain’s new underclass.

Compared with Europe, Britain is doing well – it has faster growth than any other G7 country, and unemployment is 5.6%, compared to 10% in France.

Youth unemployment has fallen to 16% (still high), while NEETs (youths “not in employment, education or training”) are 12%, around the rich world average. Crime and teenage pregnancies are at record lows.

But we have lots of school dropouts, who are the most likely to be unemployed in the rich world. We have the third worst number of youngsters with poor literacy and numeracy, and the fourth worst number of those bad with technology.

This “underclass” is most common in deindustrialised areas in the north, but is also present in Midland cities, seaside towns and parts of London.

Britain’s flexible labour markets create lots of jobs for the unskilled, but this seems to exacerbate differences between the employed and the unemployed.

The literacy gap here is the highest in the OECD. We are also unique in that those under 30 have worse literacy and numeracy rates than those aged between 30 and 54.

Some of this is from immigration, some from low educational standards. Native children are more likely to be unemployed than children of immigrants, again uniquely in Europe.

There are knock-on effects on crime. The average conviction rate for those entering the labour market during a recession is 4% higher than for those joining it in good times.

German-style apprenticeships could be one answer. One in 4 German employers offer them, compared with one in 10 in Britain. They start earlier and last longer in Europe, too.

But maybe it is too late. Robots and software automation are coming for the unskilled jobs (en route to the skilled jobs). The real question is what to do with those that are displaced.

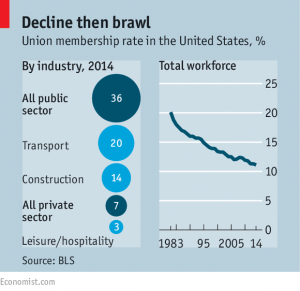

Who’s the boss?

The newspaper also reported on a US tribunal case which could reshape agency working.

A California branch of the Teamsters Union wants to organise employees of Leadpoint Business Services at a recycling plant, and wants Republic Services, a giant rubbish collection company treated as an employer too.

The National Labour Relations Board (NLRB) is expected to rule in favour of the union.

It’s a similar case to the one about whether Uber drivers are employees, self-employed or something in-between. Uber is appealing a lower-court judgement that found it liable for driver expenses.

There’s also a case where employees at a McDonald’s franchise restaurant, are trying to have McDonald’s itself treated as their employer.

These cases could affect contracting, outsourcing and franchising – a major segment of the US economy.

The current standard for determining “joint employment” is that each company must be involved in hiring, firing, discipline, supervision and direction. Responsibility must be “direct and immediate”.

It sounds like a lost cause, but the NLRB’s lawyers want this rule to be abandoned. The current system reduces the ability of workers to bargain for better wages, hours and working conditions.

If things changed, companies would suddenly be responsible for their cleaners and janitors. Large businesses would come under pressure to integrate vertically, with all the potential inefficiencies that brings.

Let’s hope these cases fail.

Graduate stock

The Economist also reported on the possibility of funding students with equity rather than debt.

Britain reforms student funding regularly. Currently we have:

- £9K per year tuition fees

- low-interest loans repaid from future salaries above a threshold

- outstanding balances are written off after 30 years

The argument that the state should support students is that educated citizens pay more taxes, generate more jobs and help to advance human knowledge.

There are three problems:

- poorer taxpayers who don’t go to college end up subsidising rich ones who do

- everyone subsidises the graduates who fail to earn enough to repay their loans

- universities are incentivised to sell expensive and useless courses to students who don’t care, as they won’t end up paying

Degrees also come with private gains (higher incomes – 15% return on investment in the US, according to the New York Fed).

So they could be funded by the market, saving governments (and taxpayers) money.

There would also be problems with a market / private debt system:

- not all graduates succeed, so borrowing for college is a gamble for students

- lending against an uncertain future is risky for the investor

- asset poor students have no collateral to reduce risk, so poorer students might not find funding

- some subjects would be a much better bet than others, and the poor would be locked out of “lifestyle” education

Marco Rubio, a Republican candidate for US president, has suggested that students could sell a percentage share of their future income to private investors.

This use of equity rather than debt was first mentioned by Milton Friedman in 1955.

- For students, the advantages of the loan system remain – if they end up not earning much, they don’t pay much.

- The dubious courses should not last under this system, as investors work out they won’t get their money back ((This would also be the outcome under a market / private debt system))

- To get around the variability in students’ abilities and career intentions, investors would need to pool large groups of students together (perhaps by university). ((This again is the same under the private debt approach))

The difficulty with pooling is that if the system is voluntary, those expecting to make lots of money will find it less attractive than the time wasters.

- This is what happened on a pilot scheme at Yale in the 1970s.

- A cap on lifetime repayments per student might fix this.

- Alternatively, students could be banded by expected earnings, and better offers could be made to the better candidates.

It seems to me that advantages of the proposed system accrue more from the privatisation of the financing rather that its form.

Private debt would work just as well as equity, and some mix of the two might be best of all.

I don’t expect to see either in the near future.

How the oil-price slump is reshaping the world

We end as we began with a chart, or more precisely a map. MoneyWeek took a look at a report in The Times on how the oil-price slump is reshaping the world

The map shows the world’s biggest oil importers and exporters. With Brent crude now below $50 a barrel (cf. $100 18 months ago), exporters are suffering.

- Saudi Arabia has low production costs but high public spending, and has been raising money on the bond markets for the first time in 8 years.

- Russia is now in recession and state-owned Gazprom has a £256bn, 30-year oil supply deal with China, with no protection against a low prices.

- Norway faces a slump bigger than the 2008 recession, and is dipping into its savings.

On the other hand, large importers (China, India and Japan) are profiting. The US is starting to export oil (to Mexico), even though low prices hurt its fracking industry.

Until next time.