Weekly Roundup, 6th June 2022

We begin today’s Weekly Roundup with a look at the next recession.

The next recession

The Economist looked at the likely shape of the next US recession.

- They plumped for a mild downturn followed by a painfully prolonged recovery.

Larry Summers has observed [that] whenever inflation has risen above 4% and unemployment has dipped below 4% – economic overheating – America has suffered a recession within two years. It is well across both thresholds now.

No one thinks that inflation is transitory, and we all expect tighter monetary policy.

The question is how tight, and therefore how much the economy could suffer.

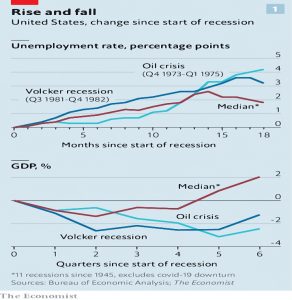

To work out the shape of the next recession, the Economist looked back to the 12 recessions since 1945.

- There are problems in the parallels with the commonly cited recessions of the 1980s (Volcker), 1970s (oil crisis) and 2000 (dot com).

Inflation is nowhere near as entrenched as at the start of Mr Volcker’s era. Growth is far less energy-intensive than in the 1970s. And the economy faces more complex crosswinds now than it did after the bust of 2000.

The Covid flash crash and liquidity driven recovery of 2020-21 make the past a poor guide.

There are three reasons the newspaper plumps for a mild recession:

Households and businesses’ balance-sheets are mostly strong. Risks in the financial system appear to be manageable. The Fed, for its part, has been too slow to respond to inflation, but the credibility it has built up over the past few decades means it can still fight an effective rearguard action.

Household debt is low:

Household debt is about 75% of GDP, down from 100% on the eve of the global financial crisis of 2007-09. Annual debt payments now add up to about 9% of disposable income, about the lowest since data were first collected in 1980.

People also have excess savings from stimulus payments and reduced spending during Covid.

- In contrast, corporate debt is close to a record high, at 75% of GDP, but this partly reflects efforts to lock in record low rates.

The lowest rated bonds are in the media and entertainment sector, which includes leisure, where there ought to be firm demand.

The paradoxical result is that a swathe of low-rated companies may be positioned to fare better than most during a downturn.

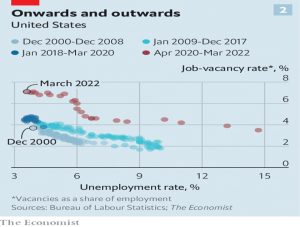

The pandemic has shifted the Beveridge Curve (the relationship between vacancies and the unemployment rate) outwards.

It now seems to require more vacancies to get to the same unemployment rates as in the past—an indication of faltering efficiency in the economy’s ability to match the right people with the right jobs.

The Economist expects the curve to move back, and unemployment to rise to 5.5% (much less than the 11% under Volcker).

Interest rates may go higher than expected, however:

If the real neutral rate, which neither stimulates nor restrains growth, is 0.5%, then the Fed would probably want to hit a real rate of about 1.5% to rein in inflation. Add on short-term inflation expectations of 4% per year, and the Fed may need to lift its nominal rate to 5.5%.

Since the Fed forecast in March was just 3%, that’s quite an overshoot.

- Rates at 5.5% would have serious market impacts – I’ve been hoping that we might top out at 3.5% in the US.

The silver lining is this would then give the Fed room for cuts to stimulate slowing growth.

Even a mild recession must be followed by an upturn for the economy to return to full health. After two years of focusing on high inflation, low growth may move back to centre-stage as the economy’s principal problem.

Soft landing

John Authers thought that the path to a soft landing was getting a little easier.

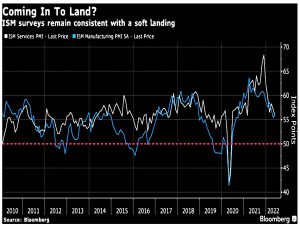

To bring down inflation without crashing the economy, we need to see data grow steadily less positive without plunging through the floor.

The ISM surveys (of supply managers) fit the bill here.

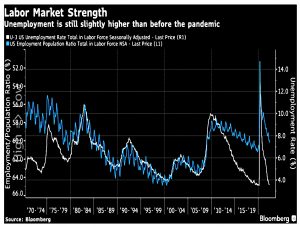

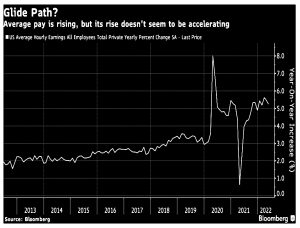

The employment market is hot, but employment levels are slightly lower than before the pandemic.

Wages are still rising, but more slowly than inflation, and the rate of increase is not accelerating.

- So we might avoid a wage-price spiral.

Mark Haefele of UBS Global Wealth Management said:

[This picture] is still consistent with our view that inflation will decelerate but remain above central bank targets, economic growth should slow below trend growth but remain above zero, and markets will end the year higher.

John is not entirely convinced (and neither am I):

if inflation is not decelerating enough by the end of the year, there would still be the possibility of further Fed hikes beyond what have been priced in. All of this is consistent with many more months of difficult trading, in which value stocks and defensive sectors make most sense.

John also looked at a presentation from Alan Blinder, a former Fed vice chairman, called Landings Hard and Soft.

A positive take on this is that a Fed tightening cycle hasn’t ended with a serious recession since the Age of Paul Volcker. The negative way to look at it is that all the cycles that ended without a hard landing happened with inflation significantly lower than it is today.

Blinder’s conclusion is much more positive:

Seven of the eleven episodes were arguably “pretty soft” landings: 1965-66, 1967- 69, 1983-84, 1988-89, 1994-95, 1999- 2000, and 2004-06. In three other cases, there was never any intention to make it “soft”: 1972-74, 1977- 80, 1980-81.

In 2004-06 and 2015-19, it certainly wasn’t tight money that caused the deep recessions that followed. So soft landings can’t be all that hard to achieve.

We’ll see soon enough.

John Lee

In his regular FT column, John Lee said that as he nears his 80th birthday, he is making some changes to the way he runs his portfolio.

The two main happenings in my stock market life over the past quarter have been the takeover of Air Partner and the derating of flavours and fragrances producer Treatt.

John expects Treatt to recover, and is holding on.

Real money is made by staying with a growing business for the long term, even if it has a “plateau” year from time to time. The lesson is: don’t be a short-term schmuck!

AP makes it more than fifty takeovers during the life of the portfolio.

- Usually, John would reinvest these proceeds into similar companies, often topping up existing holdings.

But I now increasingly focus on income, withdrawing my Isa dividends rather than reinvesting them. So two-thirds of the AP proceeds went into what I term “The Three Sisters” — Aviva, Legal & General, and M&G — on an overall 7 per cent tax-free return.

The remaining one-third went primarily into the small-caps sector, topping-up existing holdings such as Anpario, Christie, Concurrent Technologies, Lords Group Trading, Tate & Lyle, Titon, Vianet, and of course Vitec (now Videndum).

John also sold MP Evans on palm oil price strength.

- New holdings are Manolete (the insolvency litigator), Secure Trust (a bank) and STV (Scottish Television).

Carbon markets

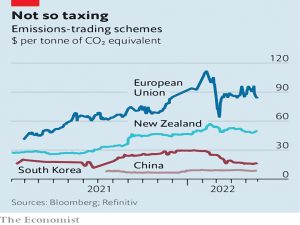

The Economist reported that carbon markets are going global, but wasn’t sure that this would make a difference.

By the end of 2021 more than 21% of the world’s emissions were covered by some form of carbon pricing, up from 15% in 2020. Trading on these markets grew by 164% last year, to €760bn ($897bn).

Carbon markets sell the right to release carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

- The idea is to disincentivise the use of fossil fuels and provide governments with funds that can be prevented in renewable energy or similar.

The issue is that the markets don’t work, with only 3.8% of emissions priced at more than $40 a tonne.

- According to the Carbon Price Leadership Coalition, this is the social breakeven price, though other economists put this price at $200 or more.

The typical mechanism is “cap and trade”, where a limit is set on annual emissions, and permits to this level are auctioned.

- Businesses can then trade the permits between themselves as required, and in some markets, investors can also trade. (( Private investors can speculate via ETFs and spread-betting ))

So a good market will have a low cap (which reduces each year) and will cover a wide range of emissions, allowing market forces to discover the cheapest way of reducing the impact of carbon.

- Such a market requires political will – since high carbon prices increase consumer prices and lower corporate profits – and this will is largely lacking.

Inclusivity is an issue:

Industrial firms argue that including them in a robust ets gives an unfair advantage to exporters from countries with a lower carbon price, which is why the EU and others offer home-grown champions a certain amount of permits for free.

Transport and buildings, where higher costs would be passed on to voters directly, are excluded from the EU ‘s scheme. Britain has long failed to raise petrol taxes in line with inflation, costing the government billions.

Scottish tax

The Times reported on news from the Institute for Fiscal Studies that imposing higher rates on income tax on residents has backfired on the Scottish Government.

- Tax revenues are £200M lower than if they had stuck with the UK tax bands.

This is not a surprise to me, since interventions in markets often produce the opposite effect from the one intended.

Quick Links

I have just three for you this week, the first two from The Economist:

- The Economist looked at the changing American consumer

- And explained why oil prices are spiking again.

- Alpha Architect looked at short-term momentum.

Until next time.